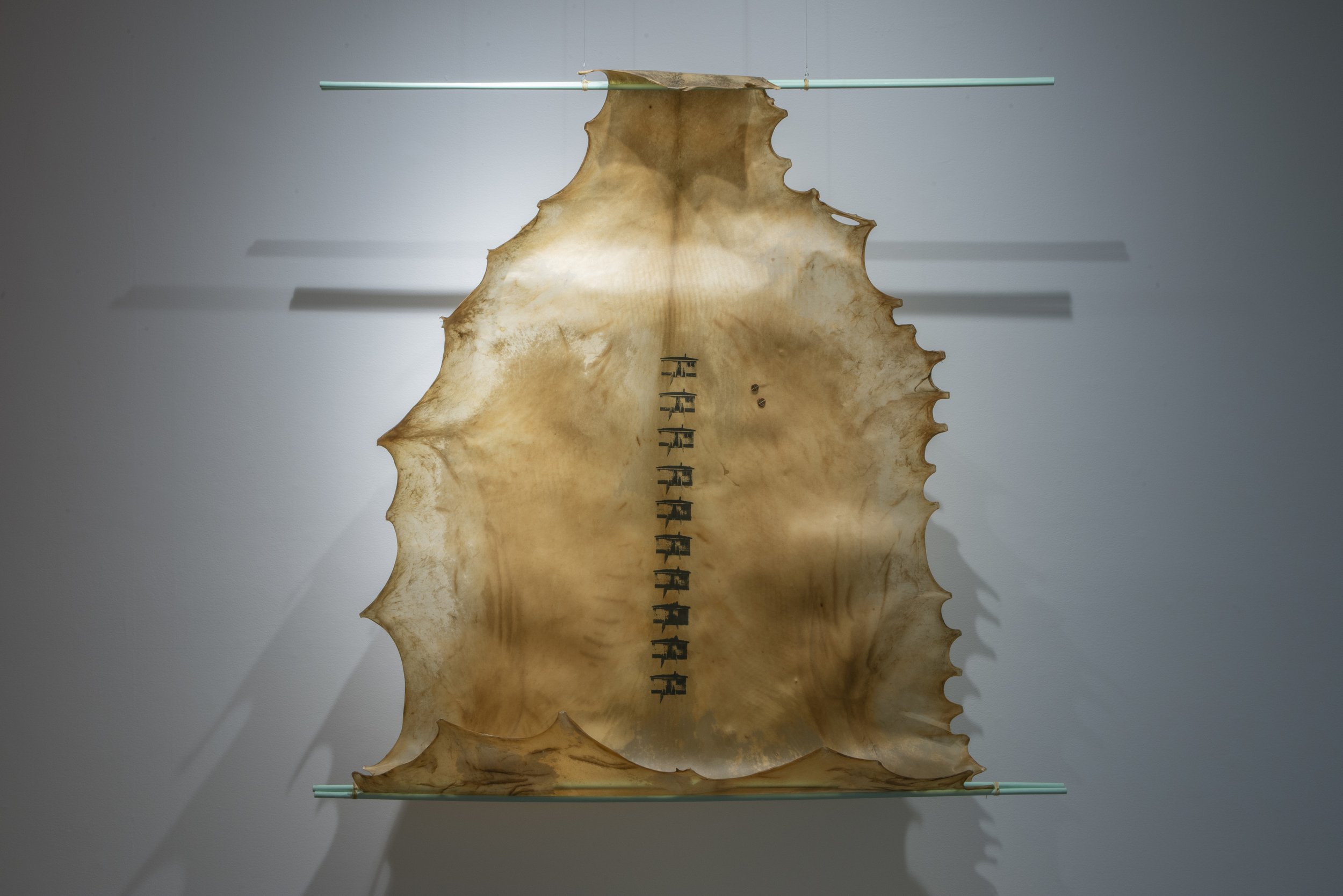

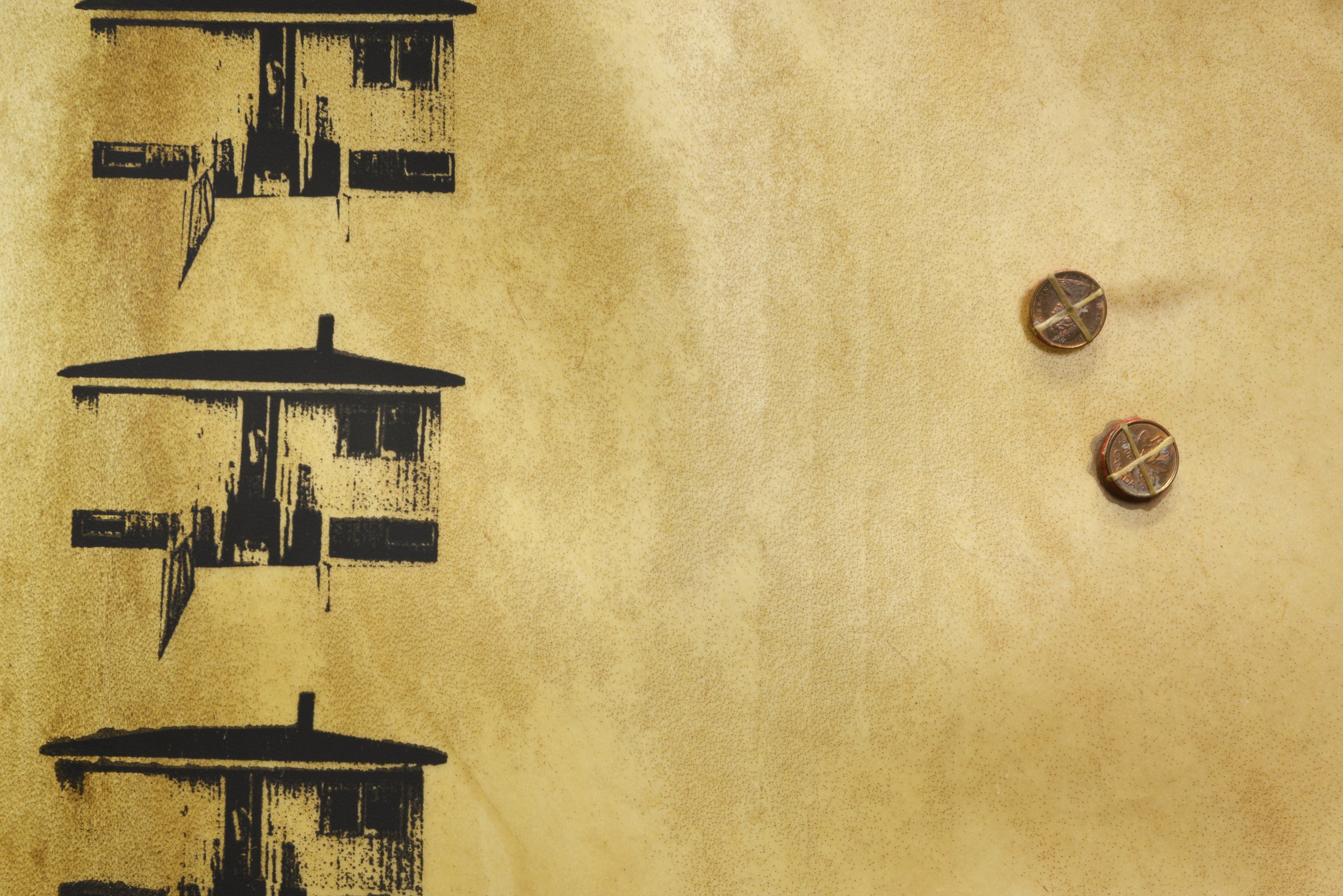

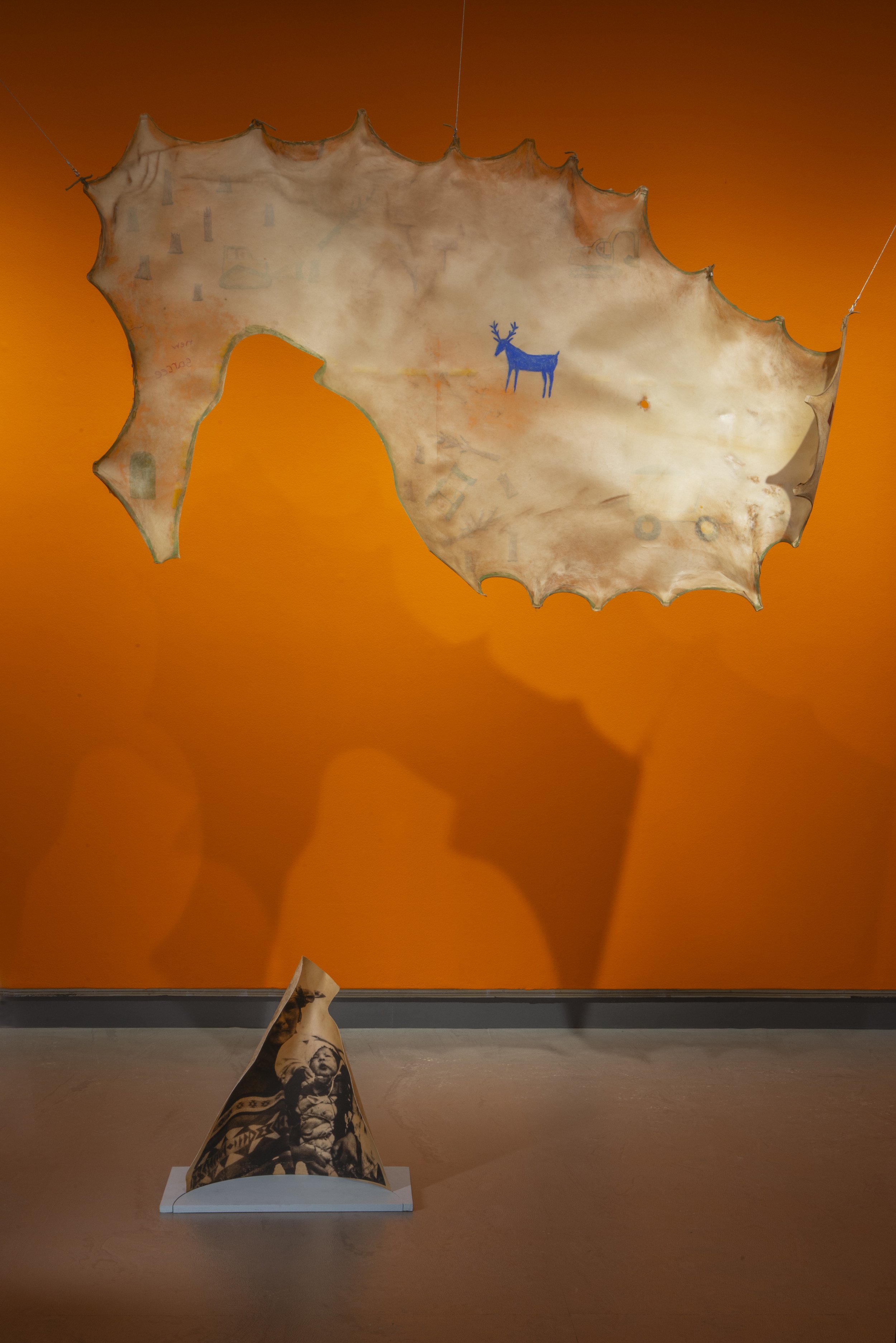

tīná gúyáńí, ina, elk parfleche, traditional paint pigments, wood dowel, pendleton blanket, 2019.

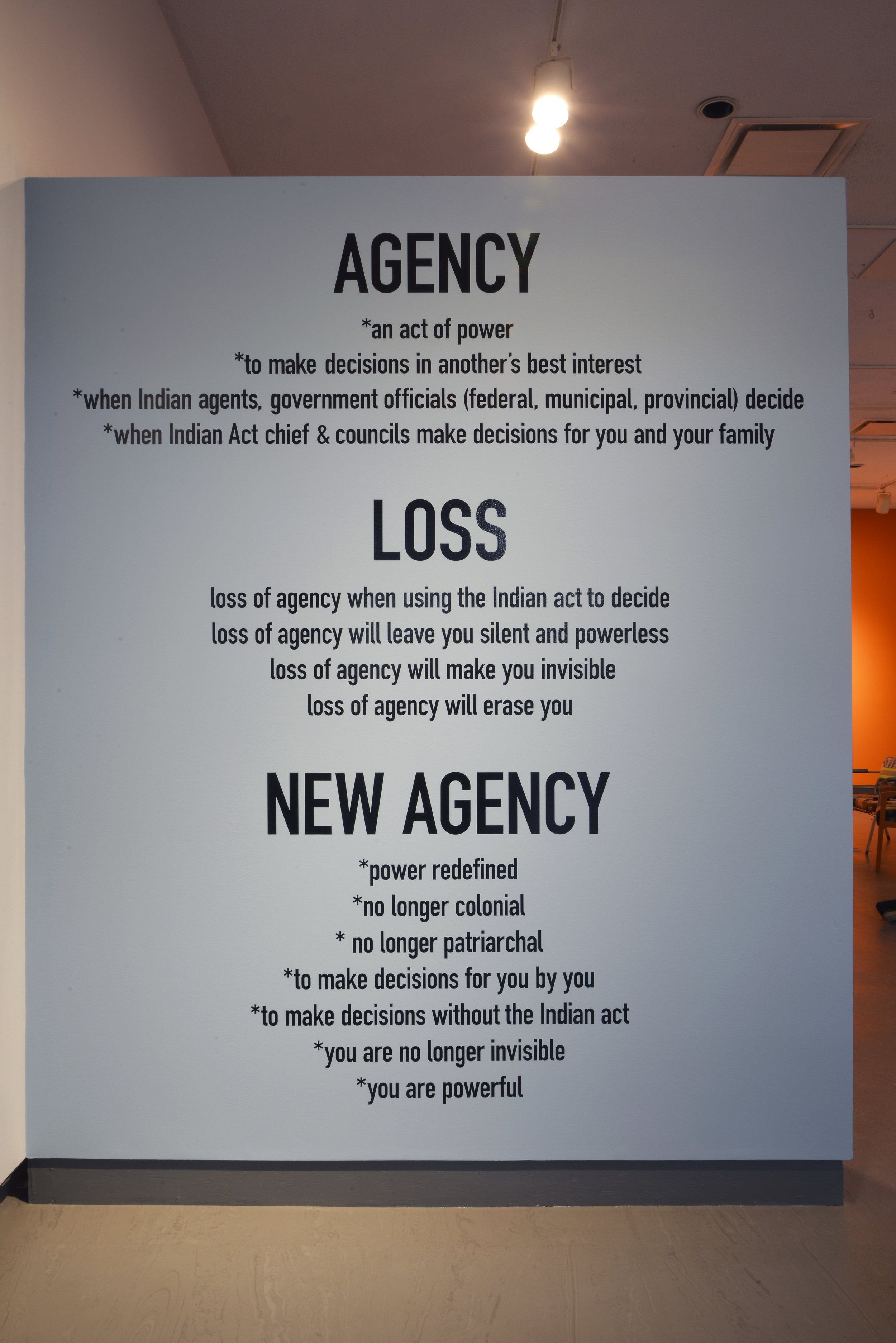

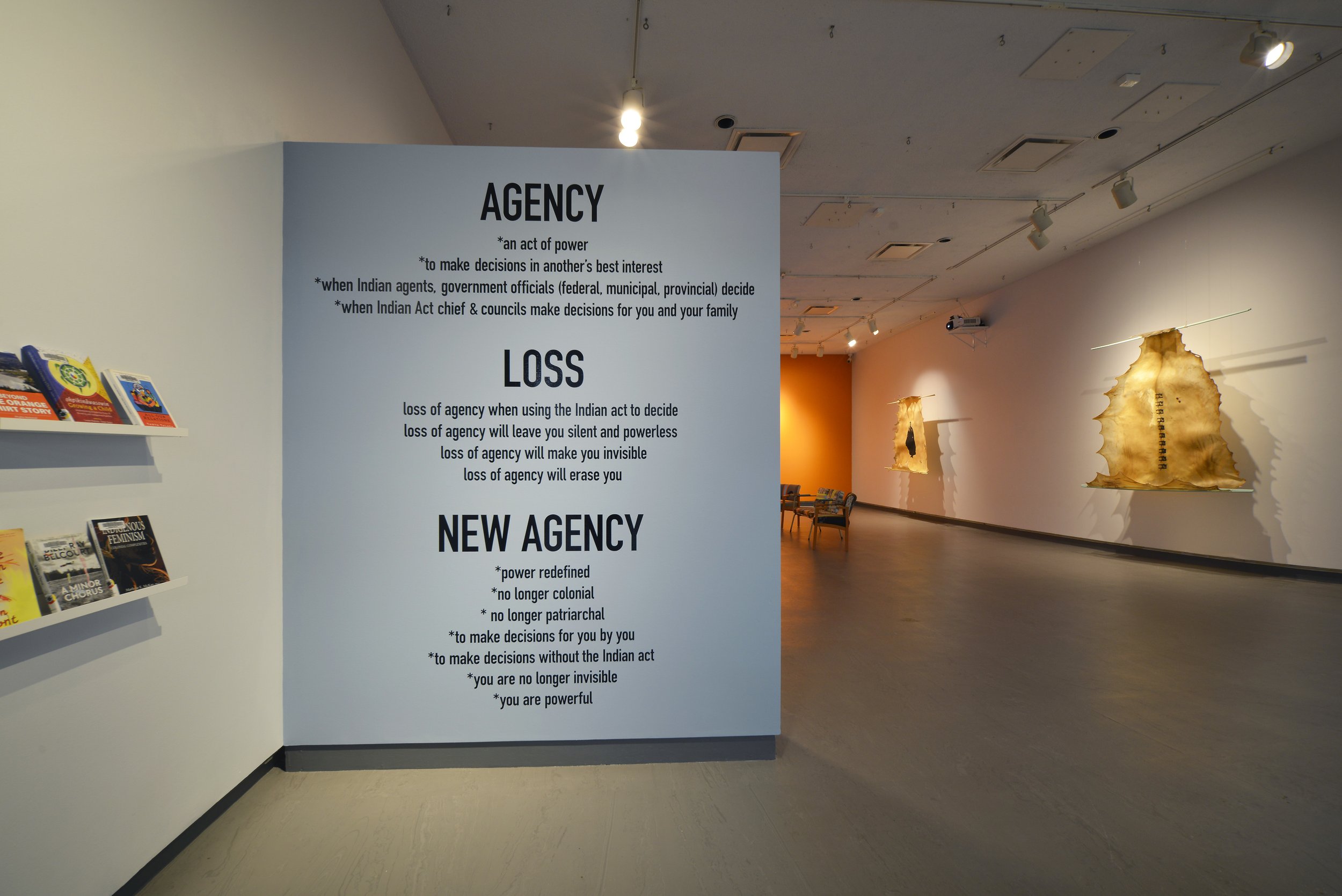

AGENCY

*an act of power

*to make decisions in another's best interest

*when Indian agents & government officials (federal, municipal, provincial) decide

*when Indian Act chief & councils make decisions for you and your family

-----LOSS-----

loss of agency when using the Indian Act to decide

loss of agency will leave you silent and powerless

loss of agency will make you invisible

loss of agency will erase you

NEW AGENCY

*power redefined

*no longer colonial

*no longer patriarchal

*to make decisions for you by you

*to make decisions without the Indian act

*you are no longer invisible

*you are powerful

tīná gúyáńí (deer road) is an artist collective from guts’ists’i / mohkinstsis (Calgary) consisting of parent/child duo Glenna Cardinal (Tsuut’ina/Saddle Lake Cree) and seth cardinal dodginghorse (Tsuut’ina/Amskapi Piikani/Saddle Lake Cree). In 2014, they were forcibly removed from their homes and ancestral land on the Tsuut’ina Nation, for construction of the Southwest Calgary Ring Road. Their multidisciplinary practice honors their connection to land and explores the effects of environmental /psychological damage. tīná gúyáńí’s work is deeply based in culture, language, oral history, family photographs, and museum/archival research. Their art is an act of cultural preservation and a protest against ongoing settler colonialism.

Essay ↑

tīná gúyáńí: guwasidodi (old agency)

By Christina Reynolds

Backstory: How art collective tīná gúyáńí’s guwasidodi (old agency) exhibit came to be – and the one piece that didn’t make it to the gallery.

The interior of the little art house smelled of green tea and fresh wood varnish. On a cold and crisp day in May 2022, Glenna Cardinal, the artist who conceived the house and recently had it built, along with her son and fellow artist seth cardinal dodginghorse, welcomed three visitors inside to talk. Rez House, as Cardinal named it, was a bittersweet endeavour for both mother and son who often collaborate as art collective tīná gúyáńí (deer road), which was a finalist for the 2022 Sobey Art Award.

Cardinal worked with a local builder (and through local arts grants) to build Rez House as a close replica of her isuu (grandmother) Elsie Jacobs’s home — which still stands on Tsuut’ina Nation. The original home is around 100 years old and it faces the Rocky Mountains to its west, and overlooks guts’ists’i/mohkinstsis (the City of Calgary) to its east. The home’s fading red-painted wood shell now also perches above the south west portion of the new 101-kilometre Calgary Ring Road; the old home’s foundation is now just a few feet from the road’s vast corridor and eight lanes of traffic.

But Cardinal and her immediate family are now physically separated from this ancestral home and land which used to be gently sloping forest and vegetable gardens, where their family lived since before the signing of Treaty 7 in 1877. In September 2014, they were forcibly removed from their homes on Tsuut’ina Nation to make way for the construction of the ring road. Since that day (and really, for their lifetimes — plans for the ring road loomed for 70+ years) Cardinal and her two sons, along with other family members, have been grappling with and mourning the loss of home — and what this means for their deep connection to land, language, ceremony, culture, community, family and identity.

This is the family story Cardinal and cardinal dodginghorse have been telling for years through their multidisciplinary art: a modern war painting, Super-8 movies, a Minecraft version of home, postcards, home furnishings trimmed with reflective tape used for road-construction vests, family photographs printed on library cards and silkscreened on to Pendletons and parfleche, coats and shawls emblazoned with pennies crossed out by sinew-thread Xs, evolving live performances – and now a new art house!

Anticipation was high as we stepped inside Rez House on that chilly May day. Cardinal opened a brand-new plexiglass window for fresh air, and the five of us arranged our folding chairs into a socially distanced circle, all bundled up with our mugs of steamy tea, ready to talk.

“I’m so excited!” Cardinal exclaimed, as she fiddled with a temporary space heater — a planned cast-iron stove, like the one her isuu had, was not yet in place. The conversation started full of possibilities: Rez House as a travelling exhibit (it fits on a flatbed trailer, so it’s moveable like a “tiny house”), or as a gallery space, or an art therapy classroom, or maybe, one day, as part of an artists’ retreat, or a movie house for showing family Super-8 films — as another way to keep telling her family’s story through art. And should she still paint the whole exterior red? That was still up for debate.

Tomas Jonsson, a curator at Dunlop Art Gallery, was one of the three visitors that day. He came to Tsuut’ina Nation to see these Rez House possibilities first-hand, and to talk about possibly exhibiting it in Regina. The other guests were a fellow artist, and me, a journalist who lives nearby in Calgary, who has been closely following the family’s story for years. Over the next few hours, Cardinal and cardinal dodginghorse often finished each other’s sentences as they recounted their family’s story through the story of their art.

It later turned out that logistics prevented Rez House from traveling to Regina. And while all of this might seem like a lot of backstory for an art piece that did not make it to the Dunlop’s new exhibit, guwasidodi (old agency), January 20 to April 9, 2024, Rez House was a key catalyst for the show – and is just a tiny bit of context for the eight carefully selected pieces that did travel to Regina. These artworks tell the stories shared in and held by Rez House.

One of the first pieces you’ll see when you enter the show is i am here (2019), a postcard stand filled with a series of 40 numbered cards. Pick one up (visitors are encouraged to do so). On the front of card 14/40 is a sepia-toned image of barren trees flanked by survey markers and tangles of barbed-wire fencing. Flip to the back, where cardinal dodginghorse writes: “I am here, at the South West Calgary Ring Road, walking through a small bit of my family’s forest that barely exists...” Pick up another. The story unravels in stark images and vivid prose poetry.

Throughout the exhibit, three semi-transparent elk parfleche are suspended in mid-air: ina (mother) (2019); nadisha-hi at’a (i am going home) (2023); and kuniya (come in) (2023). These modern-day war paintings and portraits feature silkscreened images of Elsie Jacobs and her mother Winnie Bull. For ina, cardinal dodginghorse used traditional paint pigments to depict the day his mother, Glenna Cardinal, first saw their trees chopped down and consumed by yellow construction vehicles for the ring road. The pictographs also recount Cardinal’s empathic encounter with a buck stranded in the tree shards who stared back at her with eyes as lost and scared as her own. On the floor below this parfleche – literally cut out from it – are a silkscreen image of Winnie Bull and her baby Elsie, showing how, through the continuing impact of the Indian Act and modern-day colonialism, women and their descendants are still being disenfranchised.

The title of this exhibit guwasidodi (old agency) connects with this continuing fight, along with another piece in the show titled new agency (2023). In this text piece printed on a wall, the artists reclaim and redefine “agency”, “loss” – and most importantly, “new agency”:

“*power redefined

*no longer colonial

*no longer patriarchal

*to make decisions for you by you

*to make decisions without the Indian act

*you are no longer invisible

*you are powerful”

The story continues along the elk parfleche spine of kuniya, which is silkscreened with 10 images of their primary family home, this one constructed in 1951, which was moved from their land for the ring road almost a decade ago now.

tīná gúyáńí’s most recent piece, her name (2023), is a 33-minute Super-8 film of family memory vignettes paired with a powerful and ethereal musical score by cardinal dodginghorse. It’s the first time the collective has created work that connects their family life growing up on Tsuut’ina also with family connections to Saddle Lake Cree Nation, north-east of Amiskwaciy-wâskahikan (Edmonton), where Cardinal’s father grew up and attended Blue Quills residential school. Cardinal’s dad had an older sister who also attended, but did not come home.

What tīná gúyáńí said recently about this film also sums up much of their approach to all the art they create: “This is not an educational film. It’s not a history of the school,” cardinal dodginghorse explains. “It’s a personal story – it’s not just big trauma dumping. As we get to the end of it, there are heavier things, but we are respectful to people in the family that are living through this. And we made this movie in a way that people in our family can watch it.” Says Cardinal: “Making this film is a way of giving to our family – we’re documenting it because no one else is. It’s art that facilitates healing.” Both cardinal dodginghorse and Cardinal credit making art with helping them to recognize and develop their own voices, and their ability to speak up and speak out. “Art gave me a voice,” Cardinal says, “especially at times when I couldn’t say the words out loud.”

Artists ↑

Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall

Media ↑

her name is a film commissioned by Gallery TPW by tīná gúyáńí (deer road), the parent/child artist-duo consisting of Glenna Cardinal and seth cardinal dodginghorse. The film explores a family story as it unfolds during Glenna’s studies at Blue Quills University near Edmonton, Alberta. In 1970, the Blue Quills Native Education Council took over operations of a former residential school and initiated the first Indigenous-owned and governed educational centre in Canada. Encountering a father and daughter’s experiences of Blue Quills at different periods of its history, her name presents “life as it is lived'' for a family navigating intergenerational colonial trauma through an Indigenous framework of healing

Content warning: This film contains content on Indian Residential Schools

The Indian Residential School Survivors Society has a 24 hour Crisis Line available for individuals in need of support: 1-866-925-4419