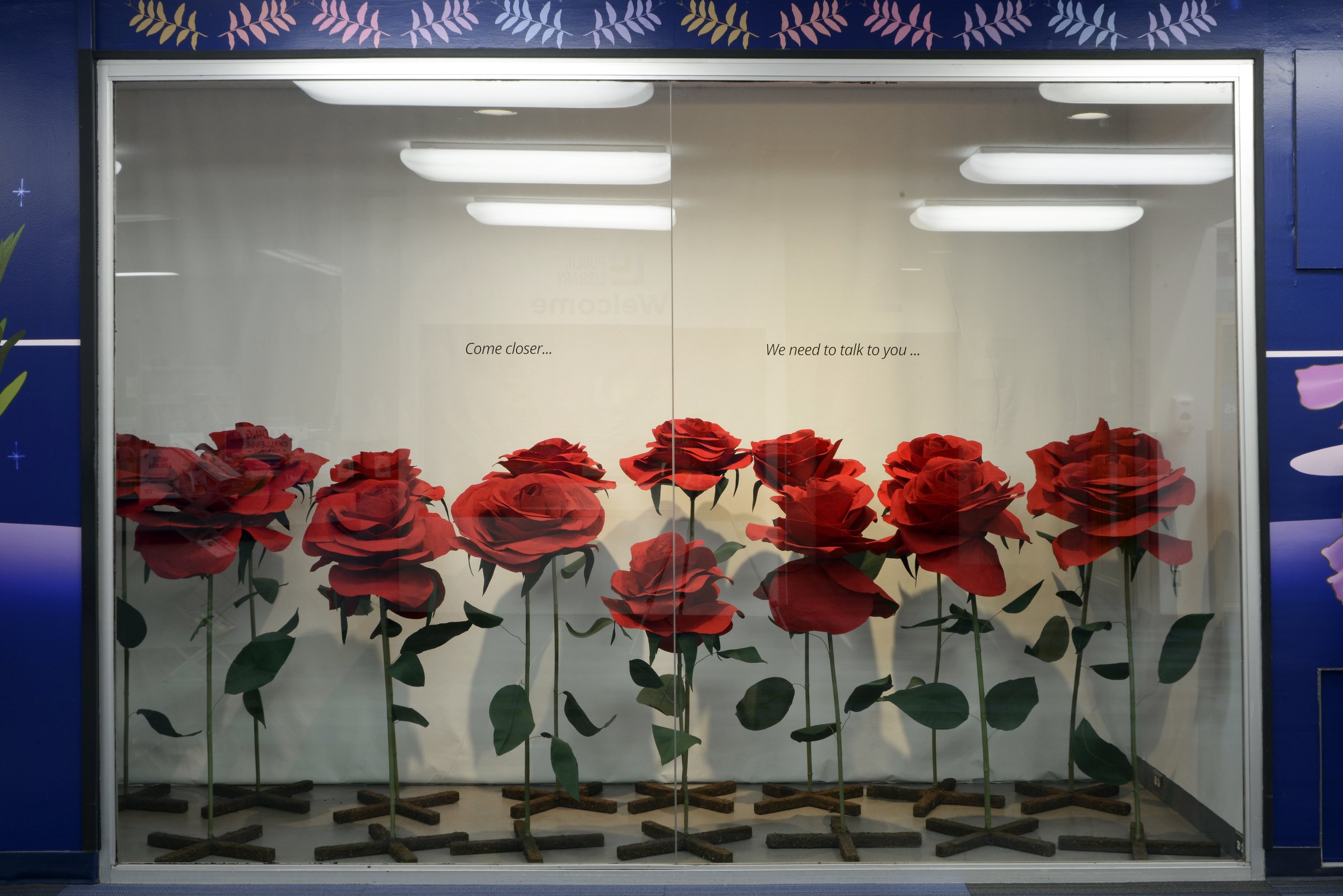

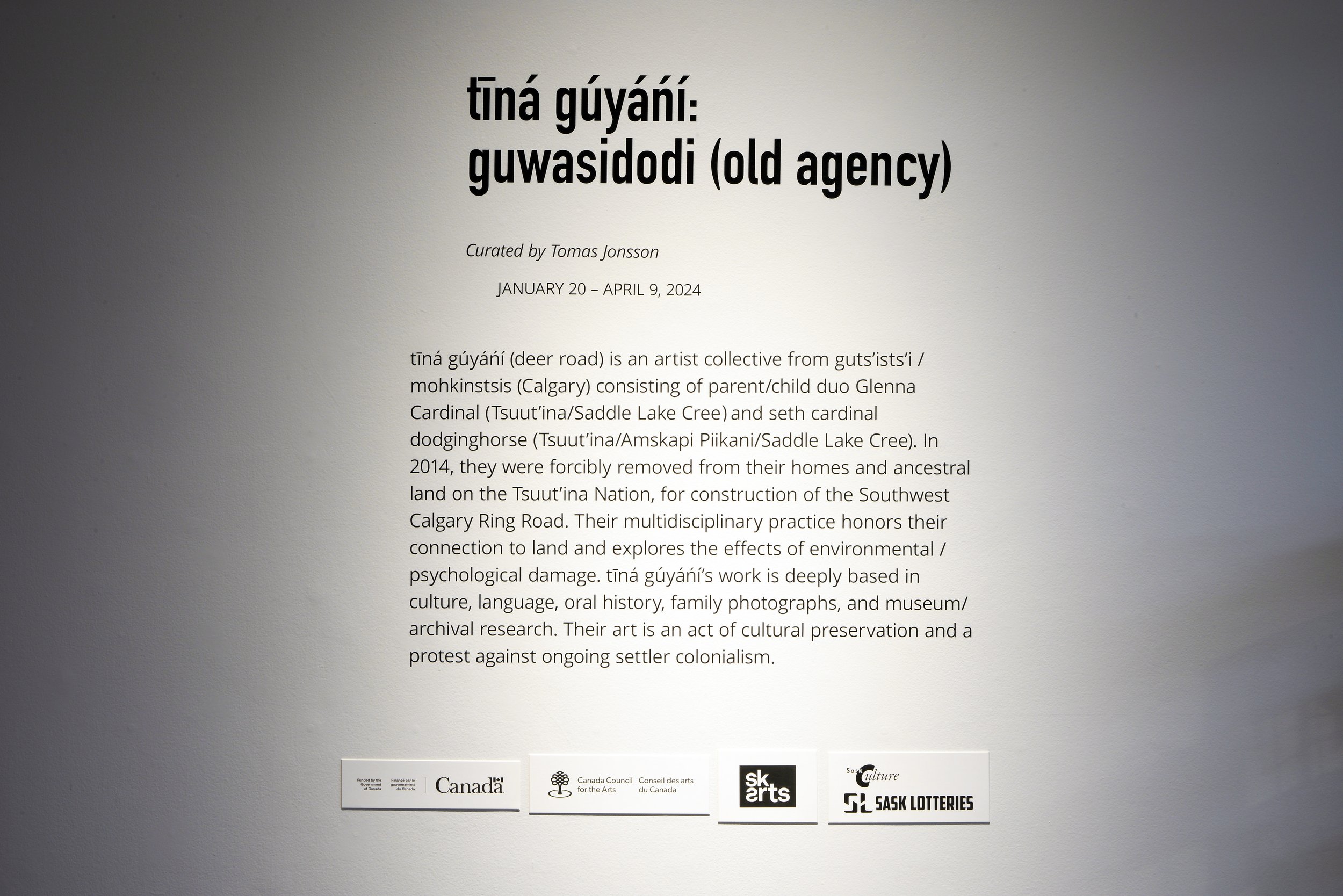

Love the Skin

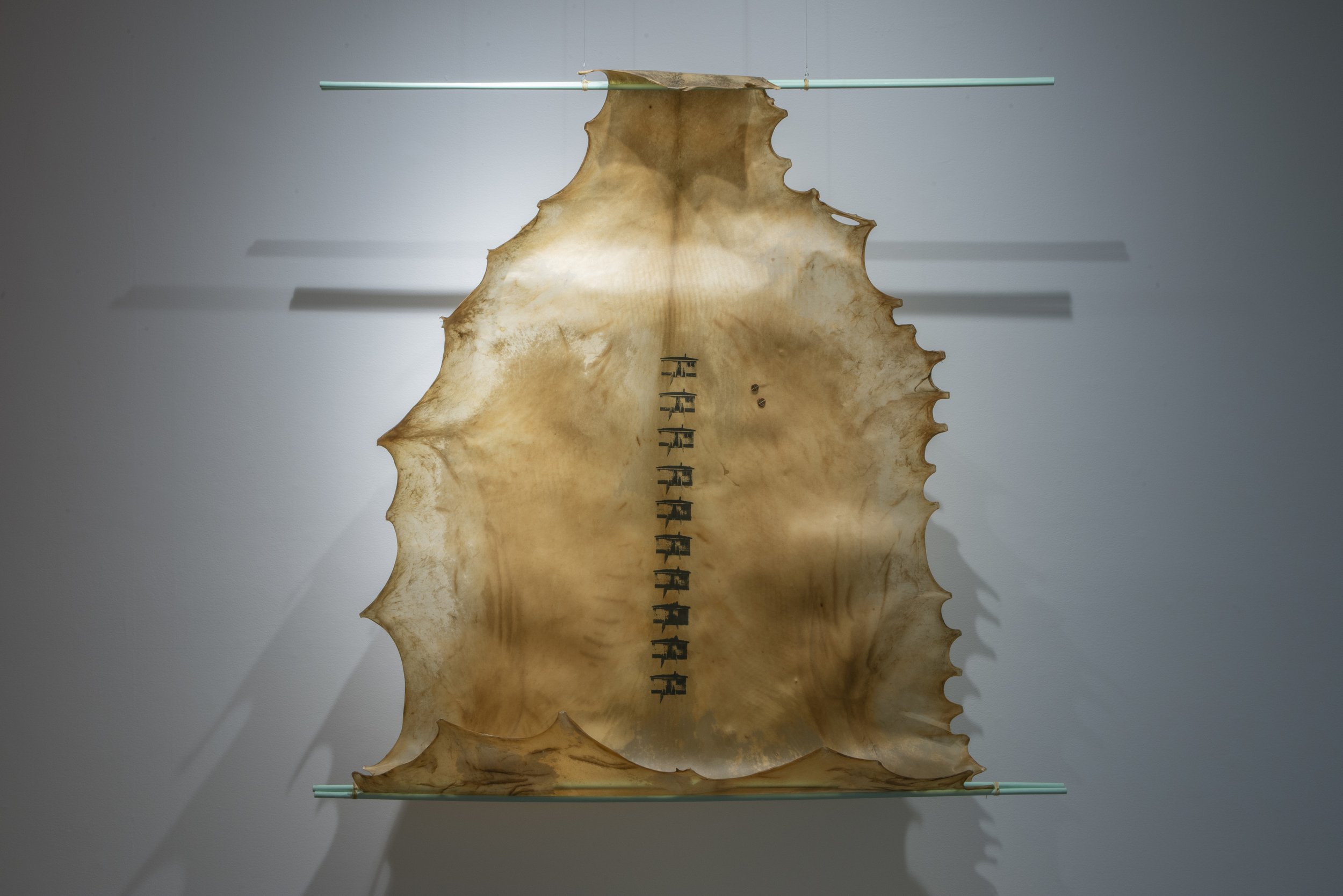

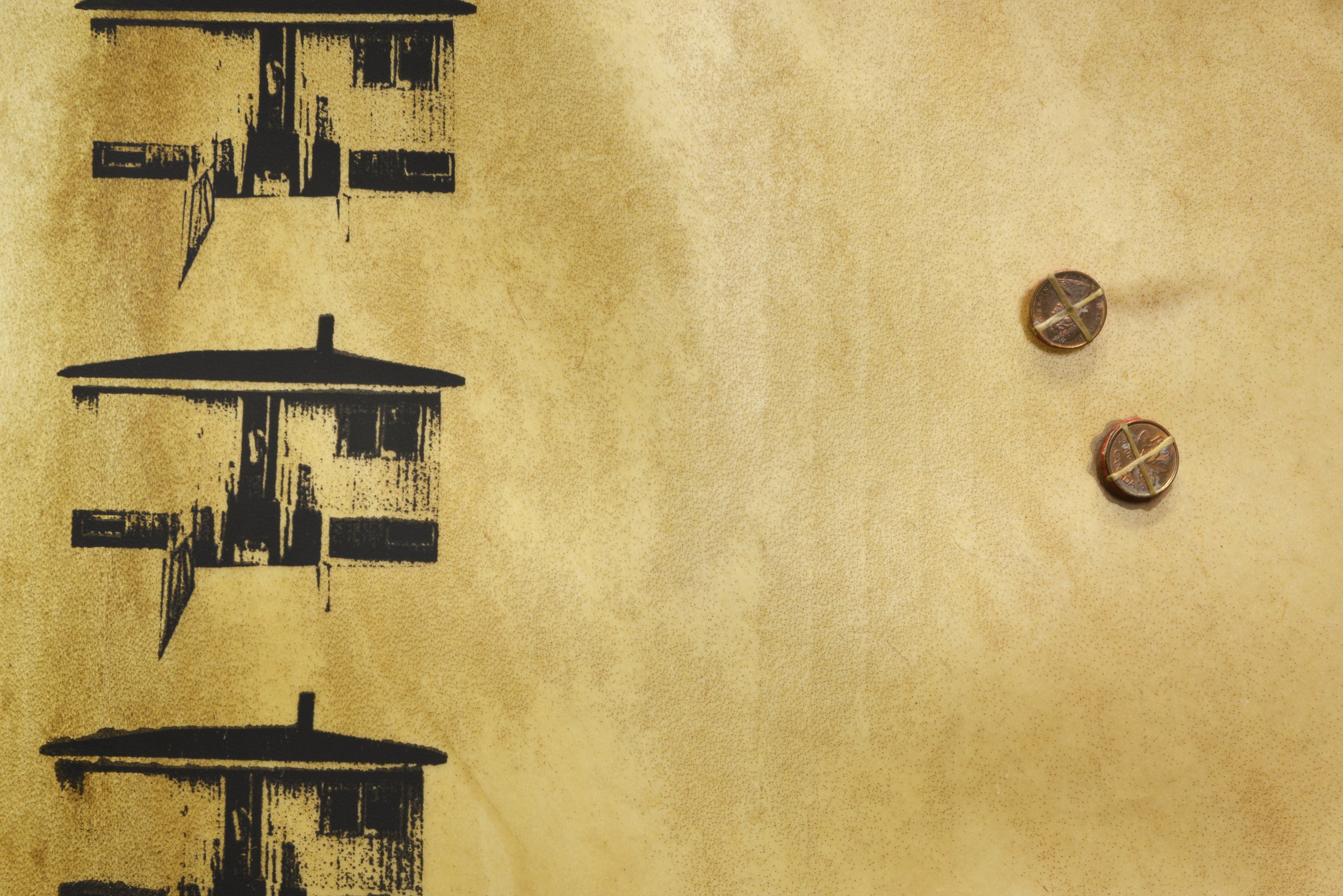

Mel Lefebvre, Healing Through Ancestral Skin Marking series, 2024

Featuring Meagan Anishinabie, Darla Campbell, Mel Lefebvre, and Amy Malbeuf.

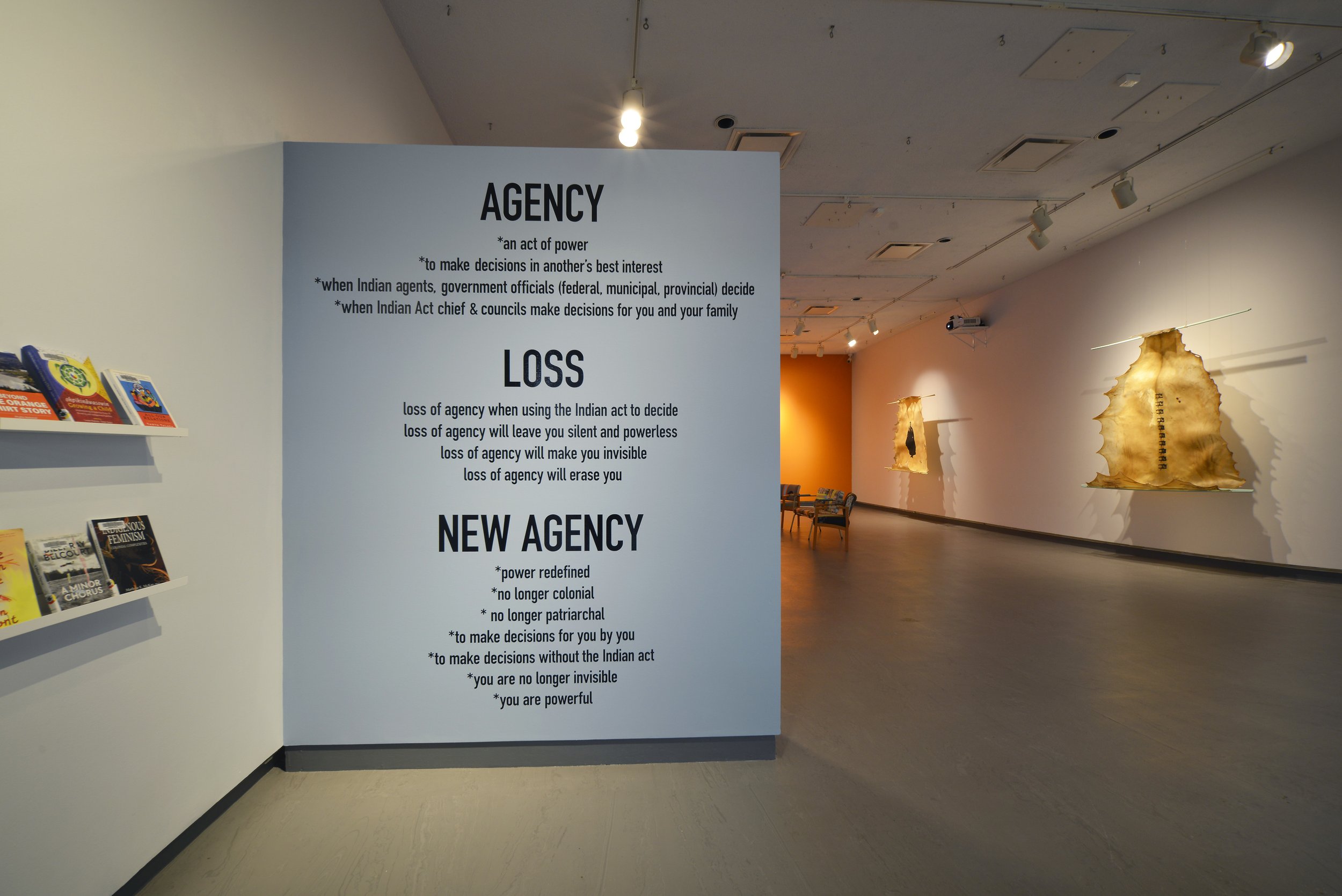

This exhibition features four Indigenous artists who work intimately with skin. It explores the act of working with skin as connection to life: people, animals, the earth, and oneself. Skin is a barrier and a form of protection, but it is also permeable and changeable. Traditionally, animal skins have been transformed into rawhide and leather for use as homes, clothes, footwear, and musical instruments since pre-history. Animal skins become a second means of protection, but also a means of self-expression and decoration. Similarly, tattoos can become clothing, protection, self-expression and decoration as a tradition in many cultures around the globe. Not only are the end products protective and beautiful but so is the creation process through the artists’ self-extension through touch, sight, and even breath as acts of deep love and care for the world around them.

Guest curator, Stacey Fayant is a Métis, Nehiyaw, Saulteaux and French visual artist from Regina, SK. Her art practice focuses on concepts surrounding identity and trauma in relation to colonialism and racism, but also in relation to healing, family, and community. She works in many mediums and is an Indigenous Cultural Tattoo Artist involved in the revitalization of Indigenous Tattooing here on Turtle Island.

Essay ↑

Love the Skin

By Stacey Fayant

In my 20 plus years as an artist, I have always gravitated to art that is work, as an act that does something positive in the world - not simply just a creation or representation of beauty. The labour involved in revitalizing cultural tattooing and traditional hide tanning is vast; it is intellectual labour, physical labour, and emotional labour. All of these being so strenuous as to only be attempted if you are truly in love with these practices.

In January of this year, Dunlop Art Gallery invited me to be to take part in the Indigenous Curator Mentorship program. I had never really done much curating, but thought this would be a new challenge and something that could expand my personal art practice and engagement with art. I was encouraged to focus on my own interests in terms of what the exhibition would be about and since much of my art centres around the revitalization of Indigenous cultural tattooing, I started with that. We secured Sherry Farrell Racette to mentor me as someone whom I respect in the community as a passionate researcher, professor, advocate, curator and artist in her own right.

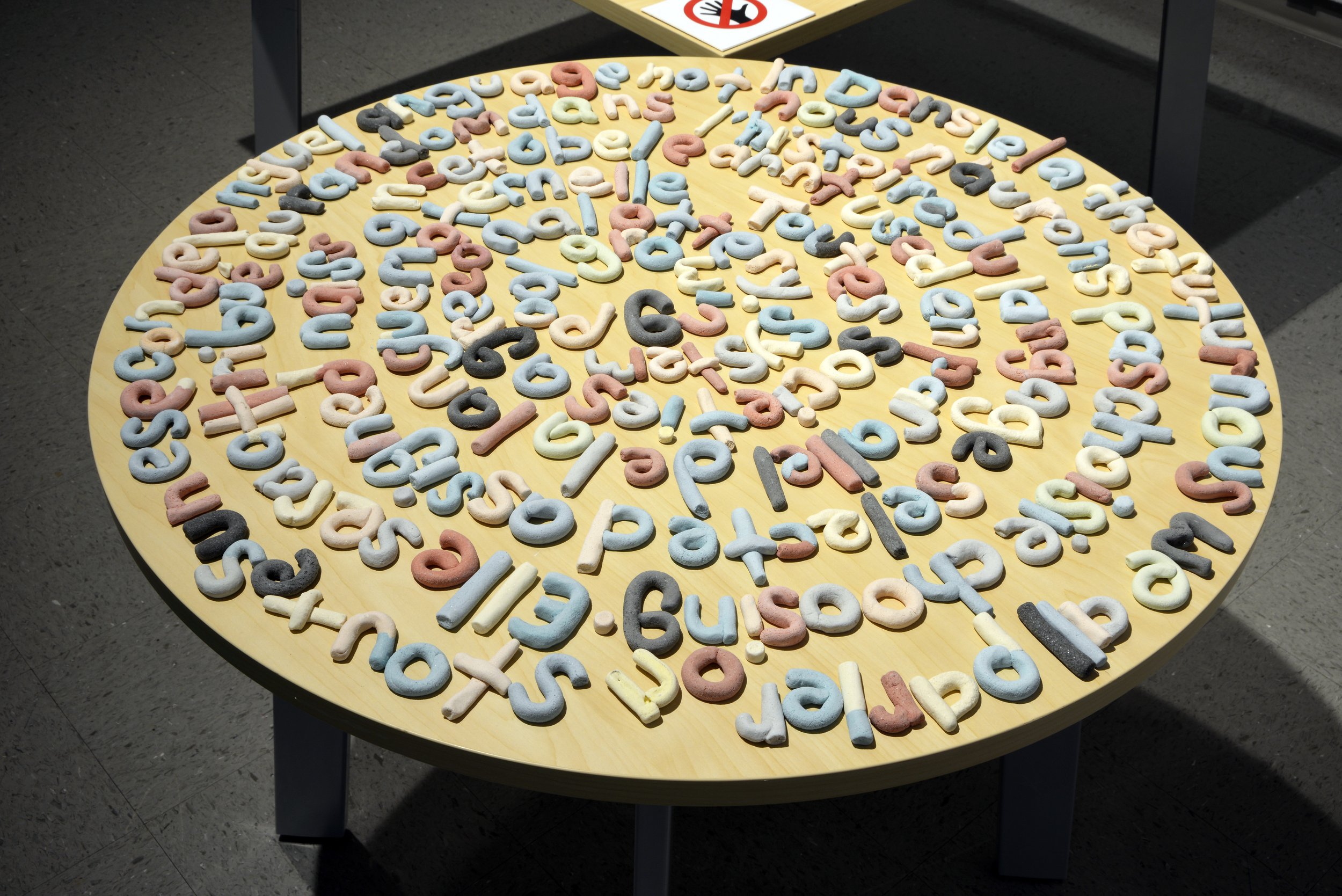

The challenge for me would be to find the hook for the show I was to curate. I slept on it and it came to me…SKIN. I wanted to bring a show together that focused and drew connections between artists who work with skin such as tattoo and leatherwork (hide tanning, sewing and beadwork).

Skin acts as barrier and protector, as communicator with the world around us, as an invitation and a boundary. It is what divides us from the world and people around us, distinguishes us as separate from each other, but also offers connection, care and understanding.

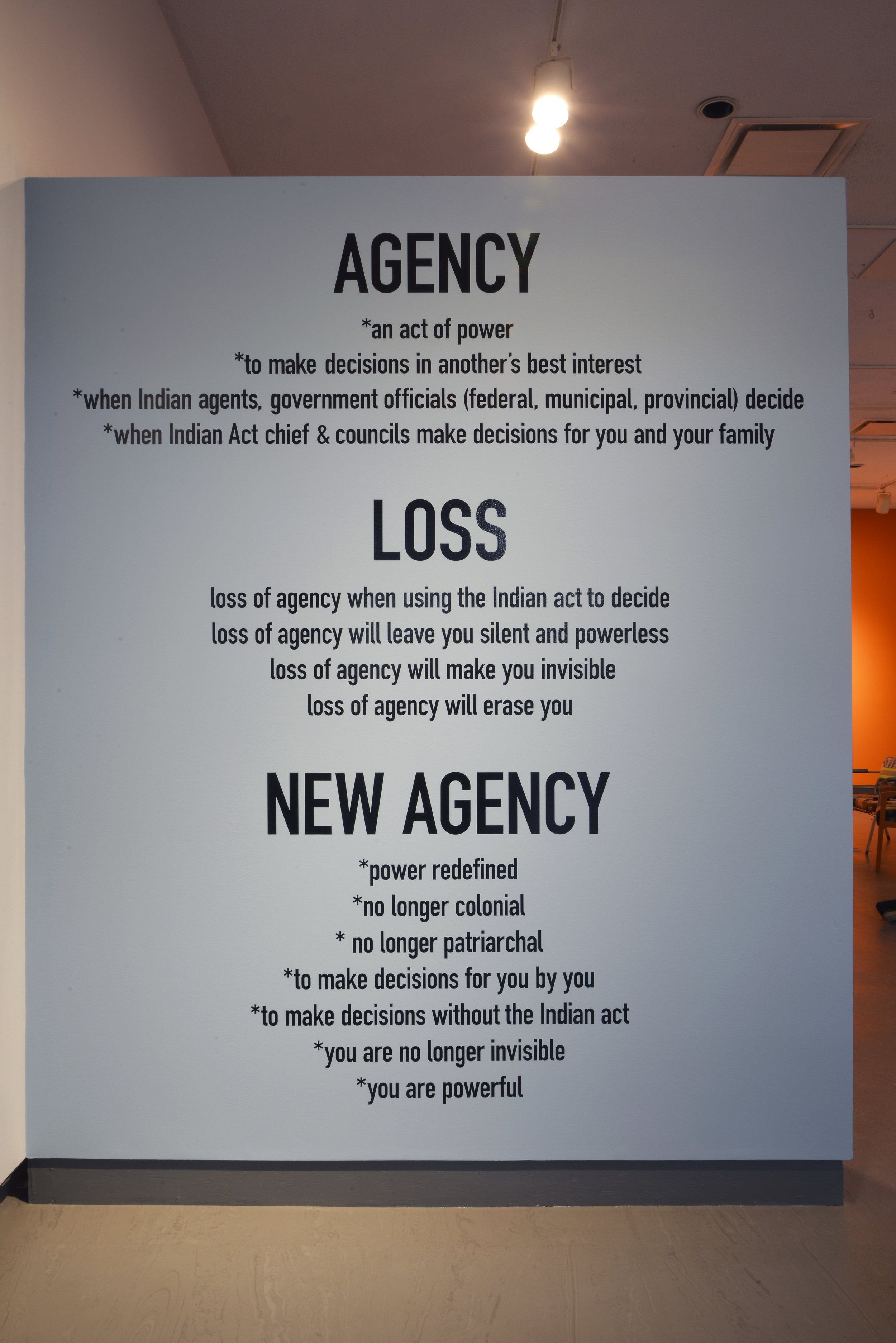

In the past few years cultural tattooing and home tanning hides into leather are both practices that are being revitalized across what we currently call Canada. These practices were a very important part of Indigenous communities prior to colonization. As with many of our cultural and community practices and our languages, they were put to sleep for generations. Skin marking and hide making were not abandoned because they no longer served a purpose or because better ways of doing them emerged. We were disengaged from them as a means of disconnecting us from each other (working together, being together, learning from each other), our identities, personal pride and self-governance, and from the land we inhabited.

My tattoo teacher Dion Kaszas has said:

The interesting thing about the revival of Indigenous tattooing is the question of,

‘why are we actually reviving something?’ It was just lost - it was purposefully

destroyed, purposefully taken away from us.

A few weeks prior to the opening of this exhibition, my family and I were able to go to a 10-day hide tanning camp at Ministikwan Lake put on by kâniyâsihk Culture Camps. I had been at this annual fall camp once before for a few days, but this time we were going as a family for the full camp and taking a deer hide to tan that my uncle had given me. I was asked to bring my tattoo kit with me, in order to give a couple people markings. This camp was a deep immersion into both the practice of hide tanning and the practice of cultural tattooing. The demand for tattoos was high and I was approached as soon as I got out of the car by many camp participants hoping to do a trade for a marking. The pressure to tattoo everyone was high, but I also knew I must work on the hide I brought and be engaged enough to actually learn the difficult processes and steps of hide tanning. I doubted I could do both. But I plugged away each day, doing the steps that needed doing for my hide and in between giving markings to folks. I managed to give 12 tattoos that week and complete my hide with my family and the help of many at the camp, fleshing, scraping, braining, softening and smoking that deer hide successfully. The experience really was exactly my vision of what the work in this exhibition are about. It was exactly what the work in this exhibition does. I was welcomed into a community and generously offered teachings and stories, friendships and food and I was trusted to give what I could in a good way.

The colonization that has and does occur in what is widely recognized as Canada is a purposeful ripping apart of families and communities in an attempt to divide and conquer the Indigenous peoples of these lands and allow for the proliferation of once European culture and beliefs systems and now Canadian culture and belief systems, but also to allow for the profits and power of these lands to be in complete control of what was once Europeans and what is now Canadians.

All cultural practices that benefitted Indigenous people by uniting them in their families, communities and nations were purposefully stripped from us. Being united in one’s family, community, and nation is love. It is a connection that is power, it conveys identity and self-respect, self-love really. When a person is valued in and by their community, they value themselves, and that value is reflected back to them as they reflect their community’s value outwardly as well. When our traditions, our knowledge, our means of connecting and being together were taken from us, all our self-value was taken as well and we were left as islands, uncared for and not having anyone to care for. Practices of skin marking, leather making, clothes making, self-decoration through tattoo and beadwork, are all practices of love, love for one’s self, one’s family and community members. In these practices we revitalize how to love again.

Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall

Media ↑