Art to Art

Leah Marie Dorion, Moon Song, 2020, acrylic, mica flakes, on canvas. (left)

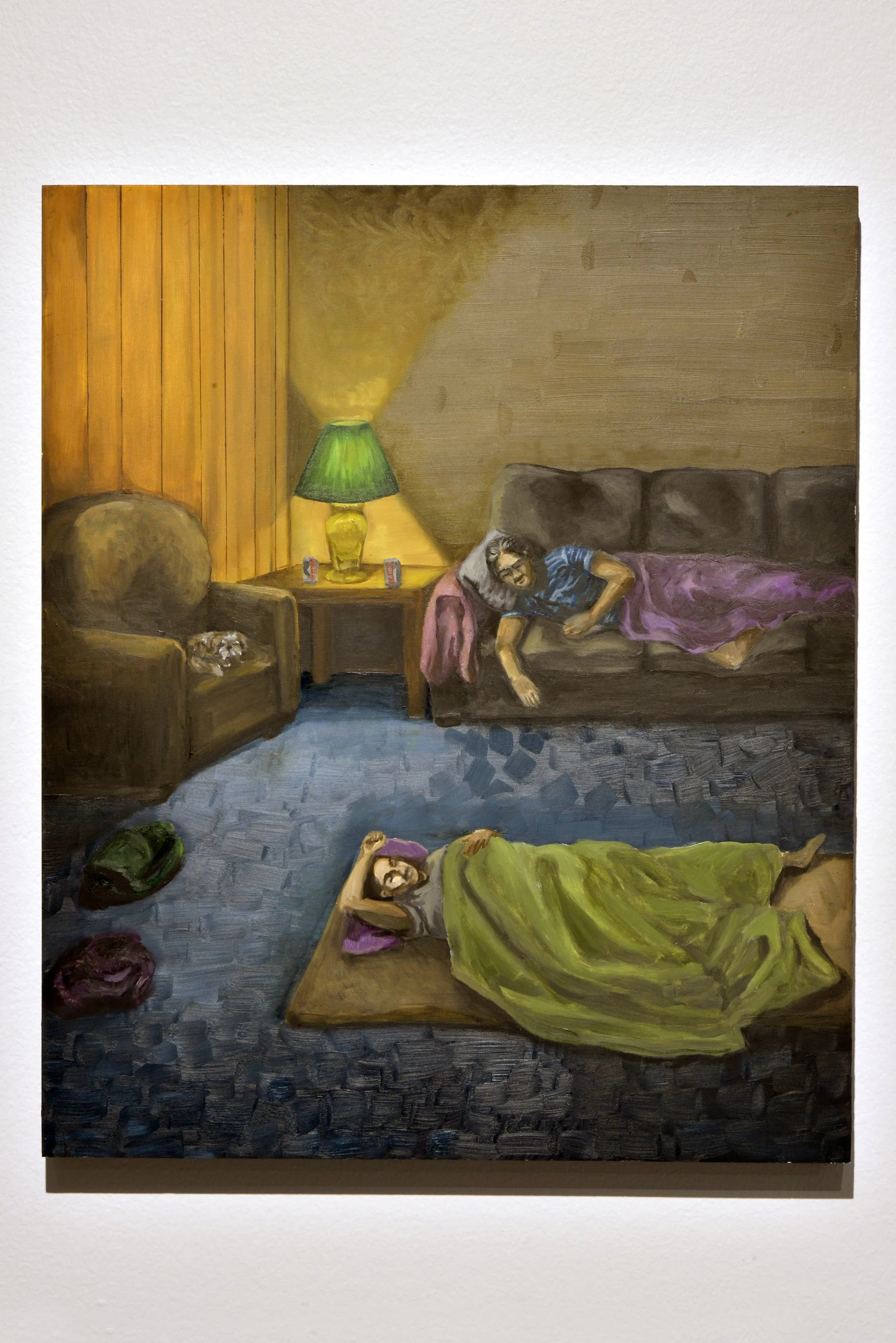

Holly Aubichon, Sundays, 2024, oil painting on birch circular panel. (right)

This exhibition brings together artworks from the permanent collections of Regina Public Library and SK Arts. The exhibition presents works by 18 artists from Saskatchewan or Prairie region, paired as diptychs to spark conversation, inviting viewers to uncover connections, contrasts, and new meanings. Take your time to look closely and discover what ideas, relationships, and interplay emerge between the works. Think about how your history and perspectives shape your understanding of the artwork.

Artworks by Holly Aubichon, Christi Belcourt, Katherine Boyer, Jerry Didur, Leah Marie Dorion, Brenda Dowedoff, Gabriela García-Luna, Grace Holyer, Marsha Kennedy, Ronald Kostyniuk, Zachari Logan, Mahdi Mahdian, Brenda Francis Pelkey, Laura St.Pierre, Leesa Streifler, Ulrike Veith, Nic Wilson, and Hanna Yokozawa Farquharson.

Special thanks to SK Arts for the loan of artworks for this exhibition.

Essay ↑

Artists ↑

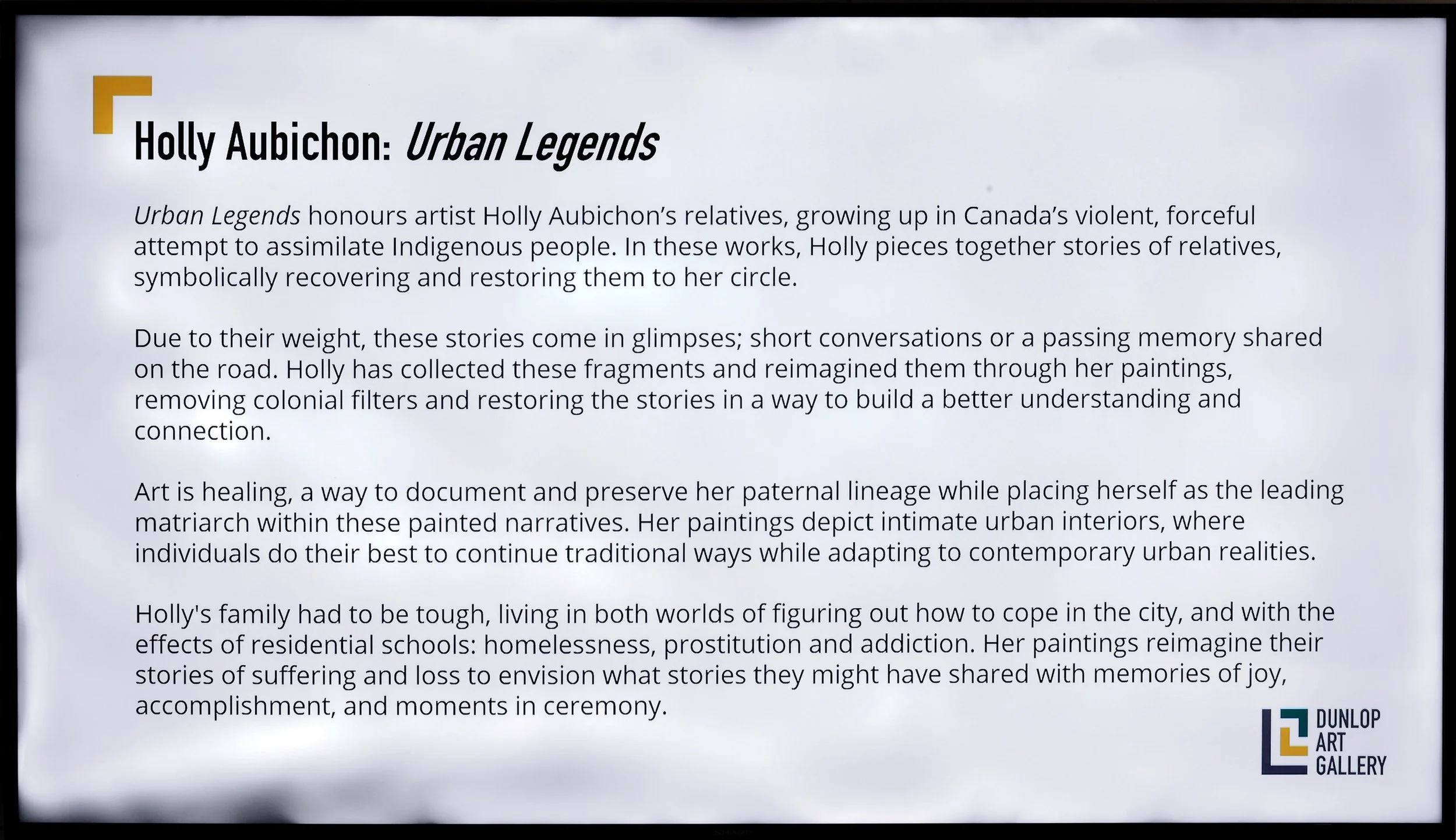

Holly Aubichon investigates topics of urban Indigeneity and how ancestral knowledge is carried through to urban spaces using memory recollection, the land, and body through forms of painting, writing, tattooing and curation. Born and raised in Regina, Saskatchewan, her Indigenous relations come from Green Lake region, SK and Lestock, SK. Aubichon’s practice is laboriously reliant on retracing familial memories and connections. She uses painting as a way to foster personal healing. As an extension of her practice, she has begun a traditional Indigenous tattoo mentorship to acknowledge the memories that bodies hold, support the healing, grieving and the revival of traditional tattoo practices. She graduated from the University of Regina in the Spring of 2021 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts, minoring in Indigenous Art History. Aubichon is the 2021 BMO 1st Art! Regional winner for Saskatchewan.

Christi Belcourt (apihtâwikosisâniskwêw / mânitow sâkahikanihk) is a Métis visual artist, designer, community organizer, and environmental and social justice advocate with roots in the historic Cree-speaking community of Manitou Sakhigan (Lac Ste. Anne), Alberta. Her work, inspired by Métis beadwork and traditional Indigenous worldviews, celebrates the natural world and addresses themes of culture, spirituality, and environmental protection. A winner of major national awards, her art appears in prominent collections across Canada and internationally. She led influential community projects including Walking With Our Sisters, a large memorial honouring missing and murdered Indigenous women, and co-founded the Onaman Collective and Nimkii Aazhibikong, dedicated to Indigenous language and cultural revitalization.

Katherine Boyer (Métis/Settler) is a multidisciplinary artist, whose work is focused on methods bound to textile arts and the handmade - primarily woodworking and beadwork. Boyer’s art and research encompass personal family narratives, entwined with Métis history, material culture, architectural spaces (human made and natural). Her work often explores boundaries between two opposing things as an effort to better understand both sides of a perceived dichotomous identity. This manifests in long, slow, and considerate laborious processes that attempt to unravel and better understand history, environmental influences, and personal memories. Boyer has received a BFA from the University of Regina (Sculpture, Printmaking) and an MFA at the University of Manitoba. She currently holds a position as an Assistant Professor at the University of Manitoba, School of Art.

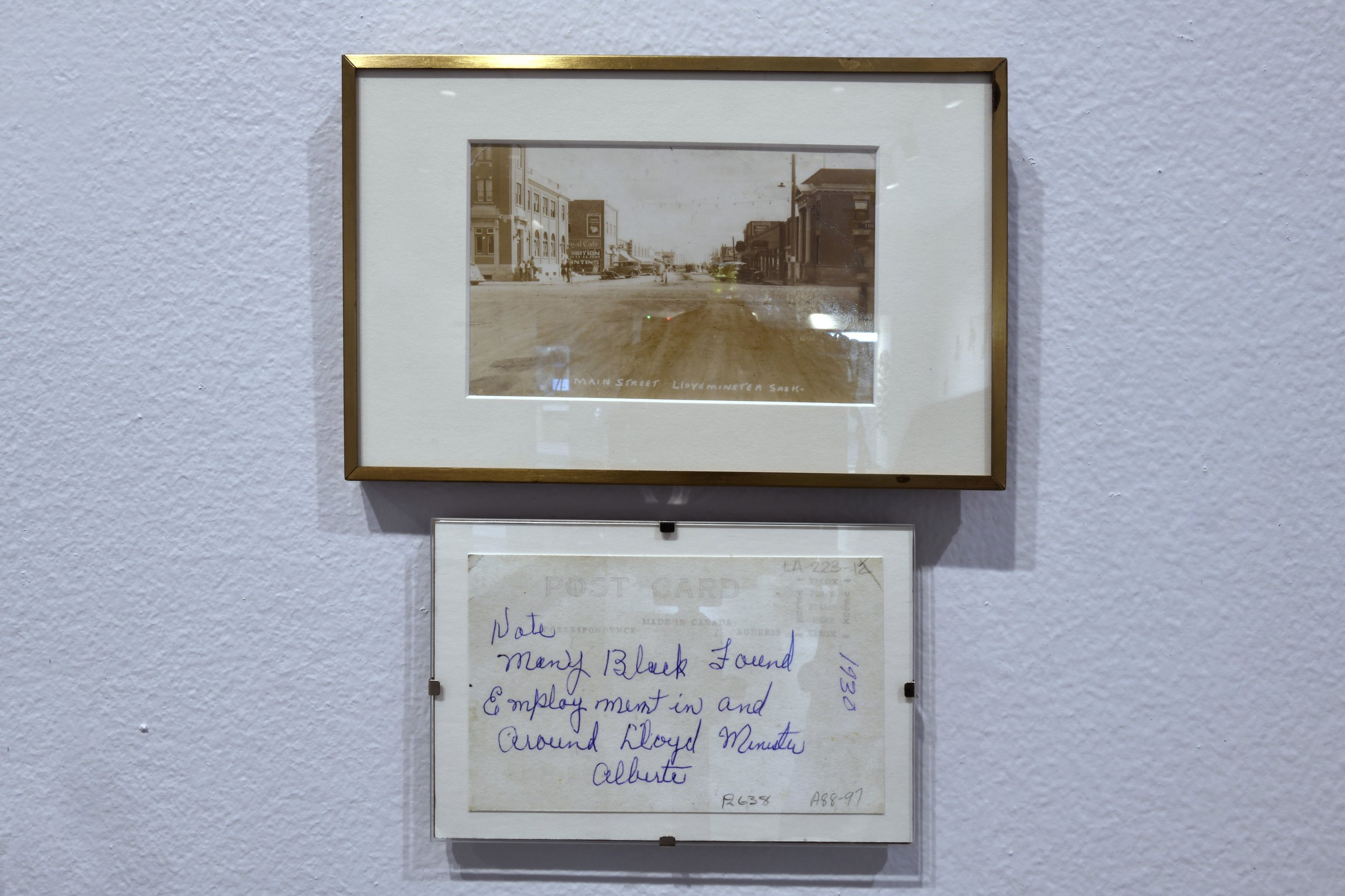

Jerry Didur was born in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. He studied ceramics at the University of Saskatchewan, receiving his BFA in 1976. Didur moved to Regina and turned to painting where he had his first solo exhibition in 1985. Didur worked in Yorkton and Lloydminster for Saskatchewan Society for Education Through Art and the Organization of Saskatchewan Arts Councils, developing arts programs and awareness in these communities. Didur has been the recipient of several grants from the Saskatchewan Arts Board. His works have been exhibited extensively and can be found in several prominent collections.

Leah Marie Dorion is an artist, teacher, filmmaker and writer from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. Dorion holds a Bachelor of Education and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Saskatchewan and a Master of Arts from Athabasca University. Dorion is also a published author of books about Métis history, cultural teachings and storytelling. She has numerous creative projects to her credit, including academic papers for the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples, children’s books, art exhibitions, and numerous video documentaries that showcase Métis culture and history. Leah’s paintings honour the spiritual strength of Indigenous women and the sacred feminine. Leah believes that women play a key role in passing on vital knowledge for all of humanity which is deeply reflected in her artistic practice. She believes women are the first teachers to the next generation.

Brenda Dowedoff (n. Desjardins) is a Métis artist of Cree, Saulteaux and French descent. Brenda was born in Neepawa, Manitoba and raised in Treaty 2 territory in southern Manitoba, currently residing in Wadena, Saskatchewan. She grew up with a proud Métis father, who made sure she knew where she came from and taught her to appreciate all that our Creator made for us. He taught her ‘to never throw away anything that the birds cannot eat.’ Which taught her to respect the earth that has been entrusted in our care. Brenda aims to use as much natural material in her products as possible.

Grace Rose Holyer was born in Weyburn, SK. Grace Holyer She earned her BFA (1989), and B Ed.(1993) at the University of Regina, and her MFA in painting at the University of Saskatchewan (1999). An artist and writer, Holyer is known for her expressionistic work in painting, artist-made books and poetry. Her writing has also been included in artwork by other artists, notably the text in Gisele Amantea’s work, “August the Sixteenth, 1984”. In 1991, Holyer’s paintings and book works were featured in a solo exhibition, “Antiromantic: The Work of Grace Rose Klatt” at what was then the Glen Elm Branch of Dunlop Art Gallery. Holyer’s work is held in several public collections, including Regina Public Library and SK Arts.

Gabriela García-Luna is a Mexican multimedia artist based in Saskatchewan whose photography‑driven practice blends analogue and digital methods through drawing, printmaking, video, and installation. Her work explores the interconnectedness of the natural world and human experience, shaped by the landscapes of Mexico, India, and Saskatchewan—including recent research on the Saskatchewan River. She has exhibited internationally and led community‑based projects in Mexico, Canada, and India. García-Luna has received support from FONCA, the SK Arts, and the Canada Council for the Arts, and her work is held in major public and private collections such as TD Bank, SK Arts, MacKenzie Art Gallery, and Global Affairs Canada. She holds an MFA from the University of Saskatchewan and a BDes from the Autonomous Metropolitan University in Mexico City.

Marsha Kennedy received a BFA at the University of Regina in1976 and an MFA in at York University (Toronto) in 1981. She taught in the Department of Visual Art at the University of Regina from 1991-2016. Kennedy’s artwork has focused primarily on the complex and interconnected relationships between humans and nature. Kennedy’s traveling retrospective exhibition titled “Embodied Ecologies”, curated and organized by Jennifer McRorie of the Moose Jaw Art Museum & Gallery, was also presented in Swift Current, Estevan, and Vernon, BC. She has had numerous exhibitions across Canada and is represented by the Slate Fine Art Gallery in Regina, SK. In 2022, Kennedy received the SK Arts Artistic Excellence Award.

Ronald Kostyniuk was born in Wakaw, Saskatchewan to a Ukrainian-Canadian family, and began his career as a high school biology teacher. Kostyniuk earned a BA in Biology and a BEd from the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon (1963); BFA, University of Alberta, Edmonton (1969); MSc (1970) and an MFA (1971), University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI USA. Kostyniuk began teaching as a professor at the University of Calgary in 1971, and is now Emeritus, retired and living in Calgary. Elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Art in 1975, he has exhibited internationally, and his work is represented in numerous collections including the Institute of Modern Art (Chicago), Canada Council Art Bank (Ottawa), MacKenzie Art Gallery (Regina), Winnipeg Art Gallery, Museum of Modern Art (Germany).

Zachari Logan is a Canadian artist whose drawing, ceramics, and installation work has been exhibited widely across North America, Europe, and Asia. He has participated in numerous international residencies, including programs in Paris, Vienna, London, New York (ISCP and Wave Hill), the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Venice's Spazio Thetis during the 2019 Biennale, and recent projects in Bulgaria and at MOCA London. Logan has collaborated with noted artists such as Ross Bleckner and Sophie Calle. His recognitions include the Lieutenant Governor’s Award for Emerging Artist, an Alumni of Influence Award from the University of Saskatchewan, and the long list for the Sobey Award. He has received funding from SK Arts, Creative Saskatchewan, Canada Council for the Arts, and the Peter S. Reed Foundation. His work is held in numerous private and public international collections.

Mahdi Mahdian is an Iranian-born figurative artist based in Regina, SK. Born in 1985 in Neyshabur, he left mechanical engineering to pursue painting, completing a BFA at the University of Tehran and MFAs from the Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts and the University of Regina. His work explores tensions between tradition and modernity, masculinity and vulnerability, and experiences of memory and displacement. Through layered, improvisational painting he blends classical realism with contemporary experimentation to convey the psychological tension between tradition and transformation. Influenced by both Old Masters and modern figurative artists, Mahdian seeks a hybrid visual language shaped by diasporic experience. He has exhibited in Iran, Ukraine, Lebanon, the U.S., and Canada, including solo and group exhibitions, and works across oil painting, large-scale drawing, and photo‑based mixed media.

Brenda Francis Pelkey was born in Kingston, Ontario. She studied art at Sir Sanford Fleming College of Applied Arts and Technology and Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario. Pelkey moved to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in 1980 and received her MFA from the University of Saskatchewan in 1994. She was an Associate Professor in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Saskatchewan from 1994 to 2003, when she moved to the University of Windsor in Windsor, Ontario. Pelkey has exhibited throughout Canada, as well as in England, Scotland, France, Germany, Czechoslovakia and Finland. Her work appears in many public and private collections, including MacKenzie Art Gallery, The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern (Saskatoon) and the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography in Ottawa, Ontario.

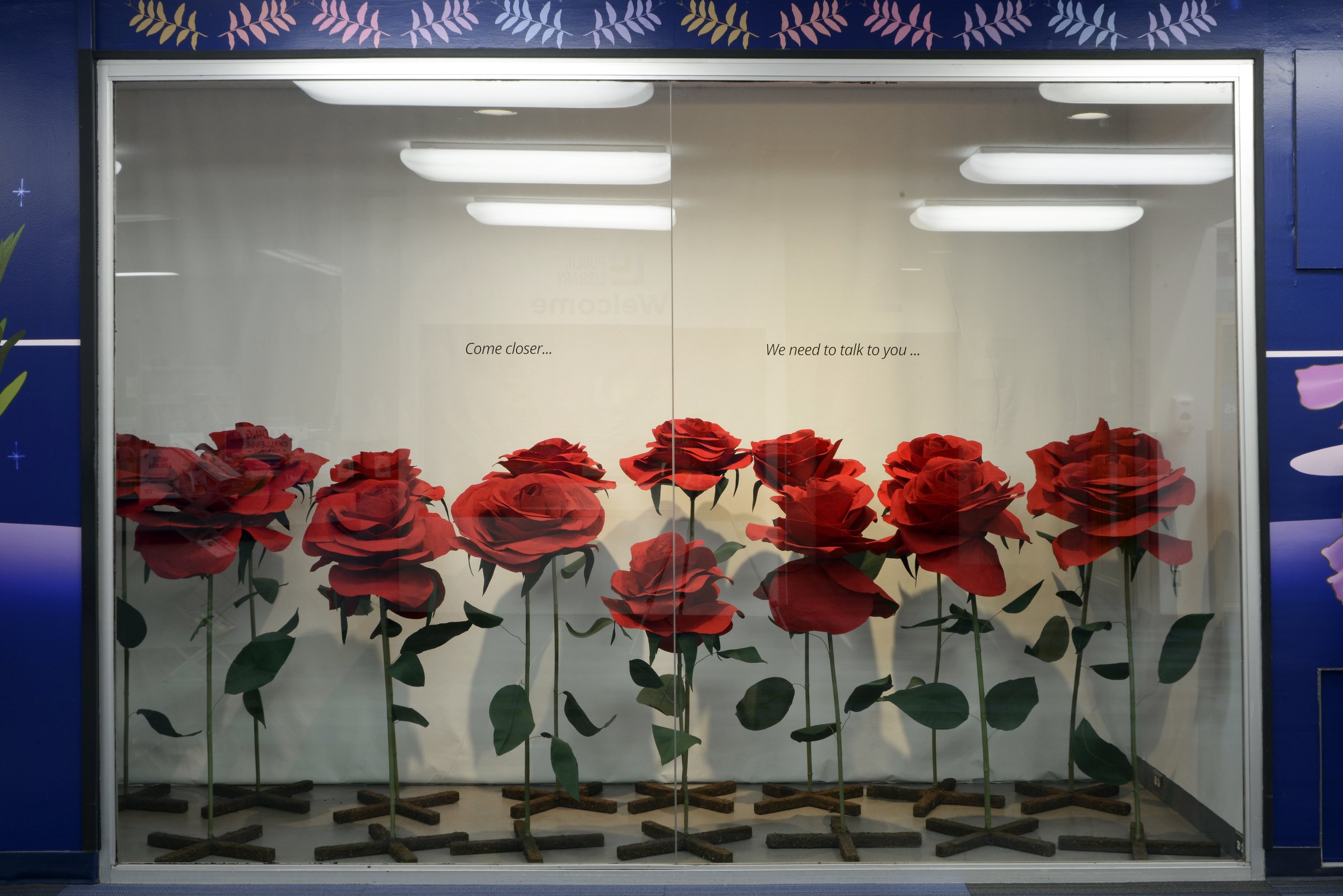

Laura St.Pierre is a Fransaskoise artist who works primarily in photo, video and installation from an ecological perspective. Her studio, located on Treaty 6 Territory, incorporates a native plant and food garden, as well as a refuge for insects, birds and wild creatures. She studied psychology at UBC and visual art at the University of Alberta and earned an MFA from Concordia University. Recent projects include participation in the international broadcast Earth (Okâwîmâw Askiy – ᐅᑳᐧᒫᐊᐧᐢᑭᕀ), as well as solo exhibitions at the MacKenzie Art Gallery, the Galerie d’art Louise et Ruben Cohen, and the Kenderdine/College Art Galleries. Her work has also been featured in BlackFlash Magazine and the Malahat Review of late. She writes about art on the prairies and teaches part time at the University of Saskatchewan.

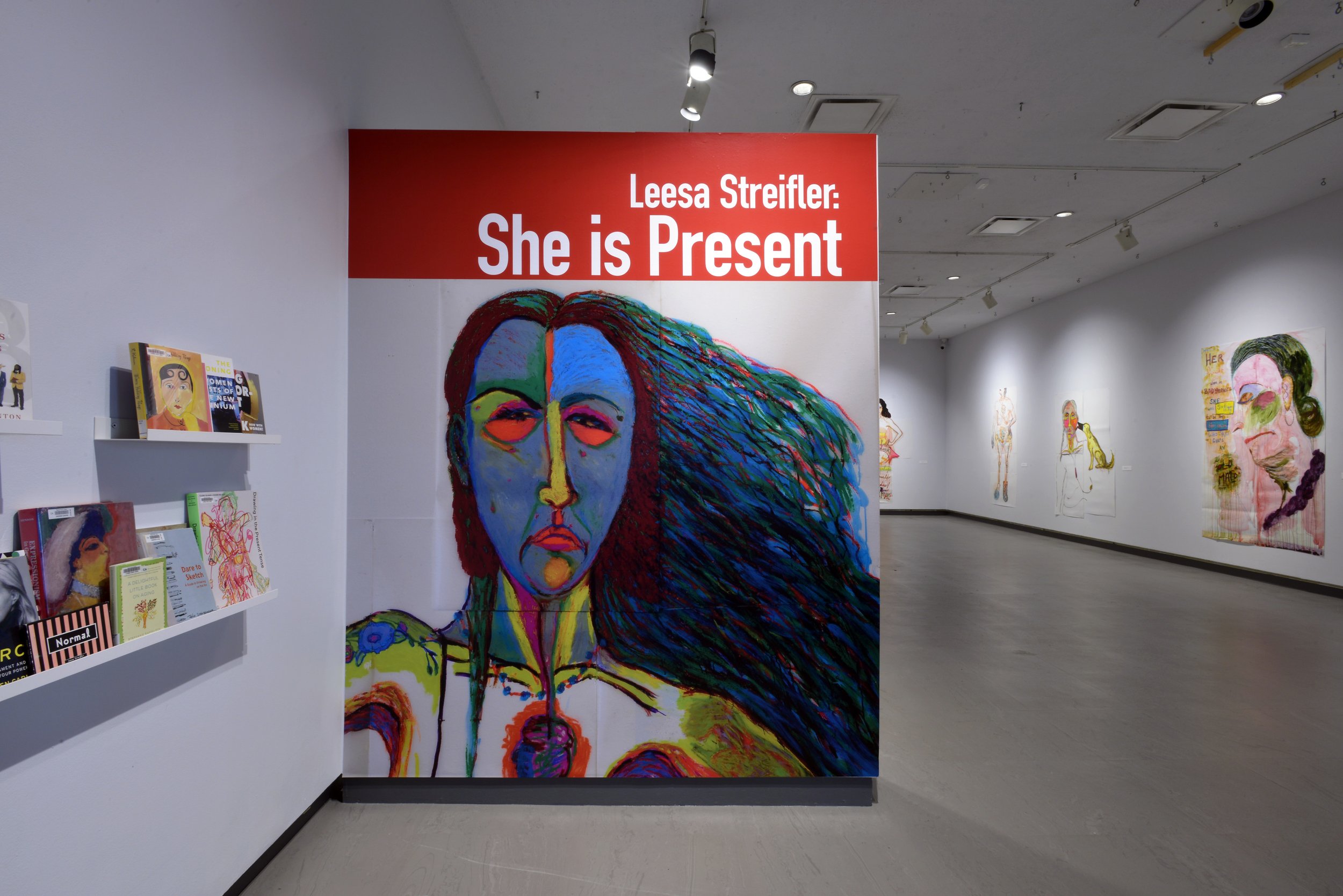

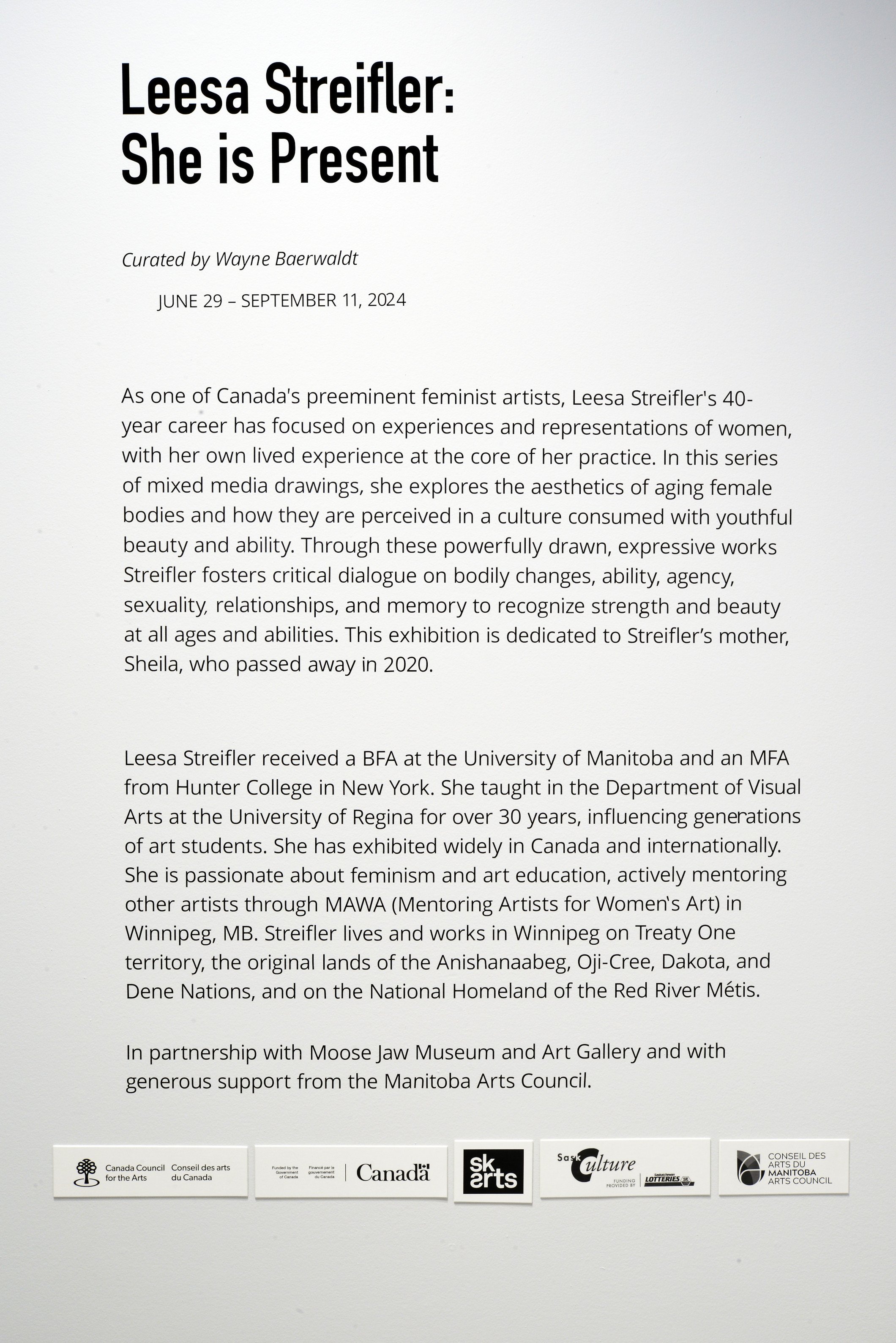

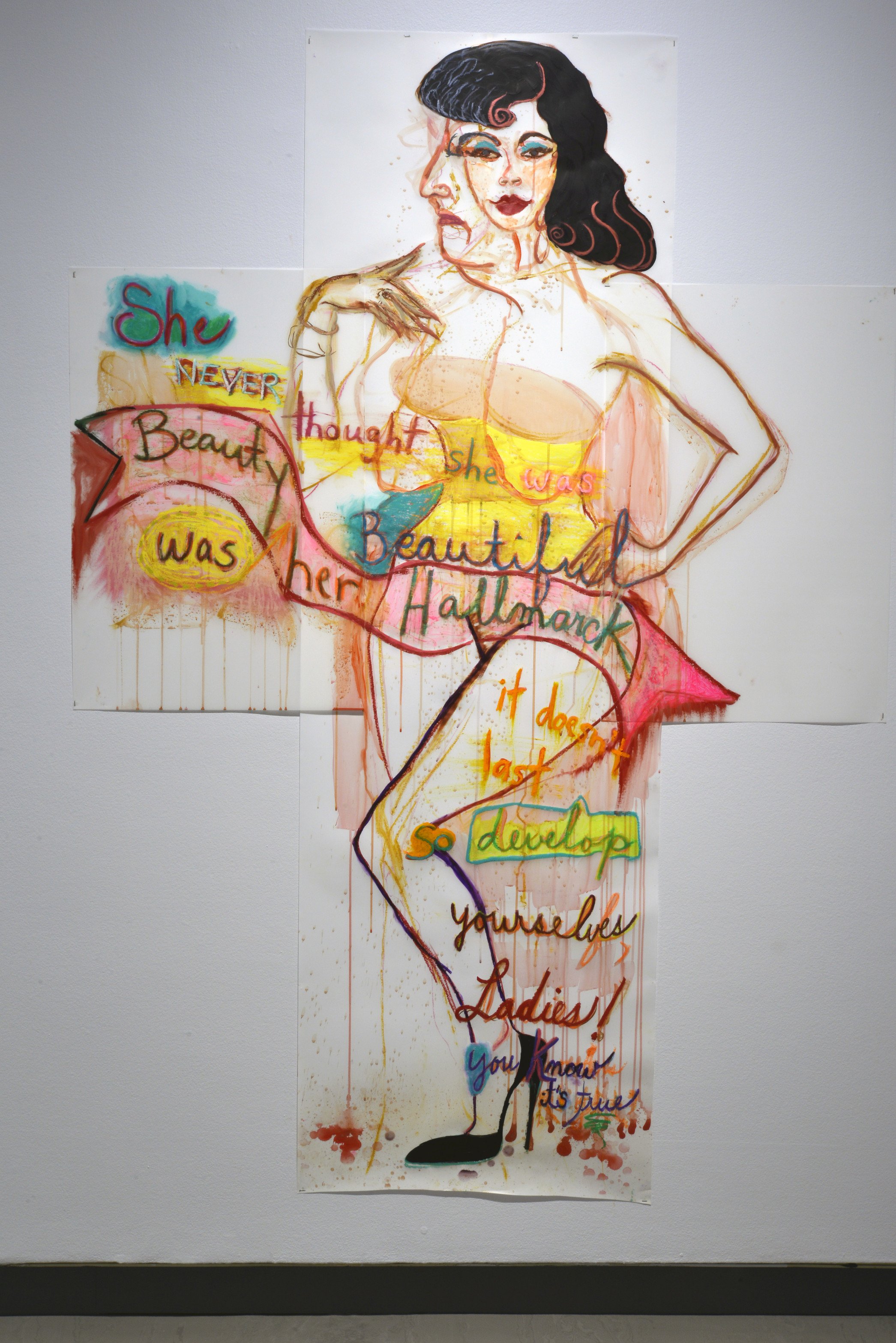

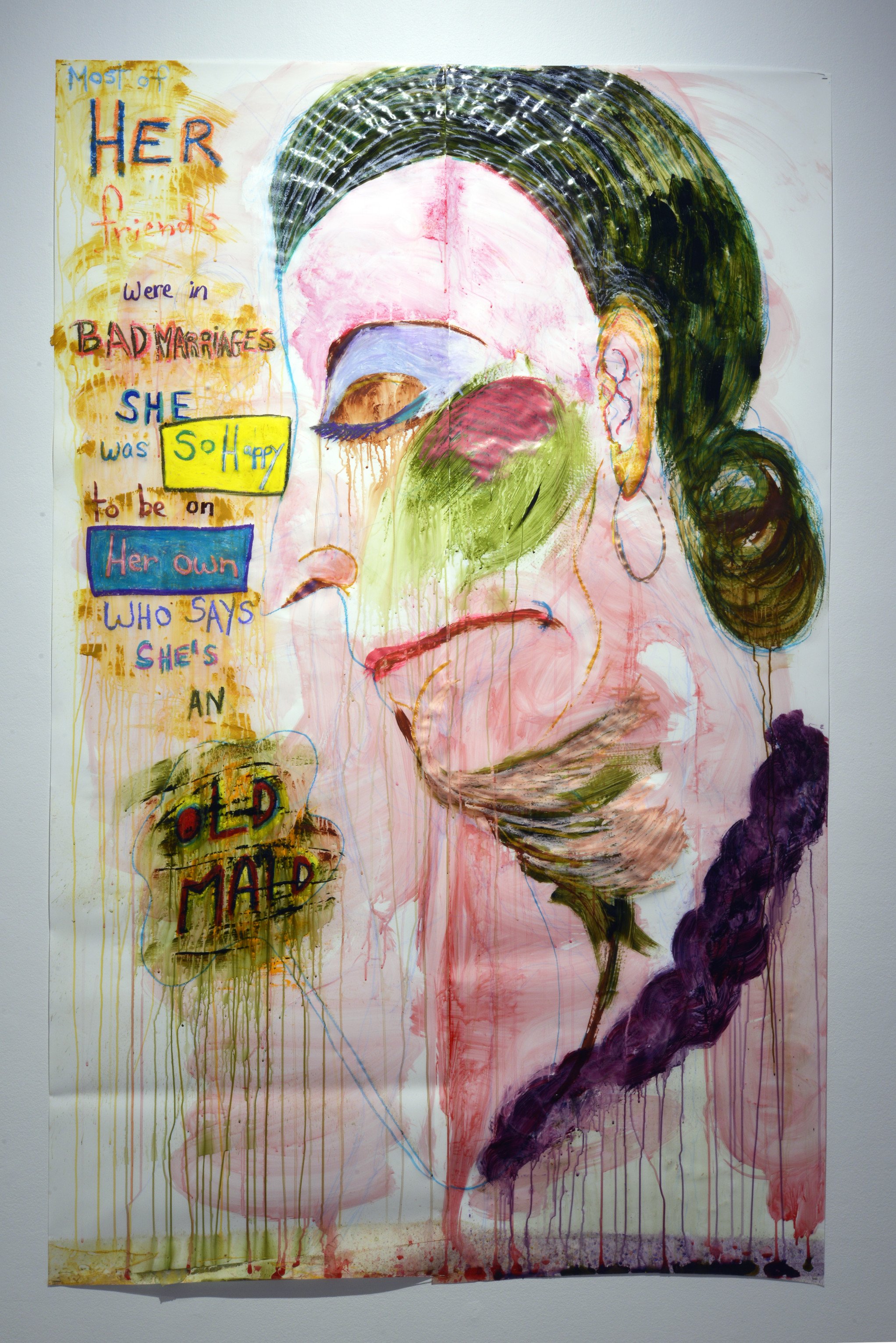

Leesa Streifler received a BFA at the University of Manitoba and an MFA from Hunter College in New York. She taught in the Department of Visual Arts at the University of Regina for over 30 years, influencing generations of art students. She has exhibited widely in Canada and internationally. She is passionate about feminism and art education, actively mentoring other artists through MAWA (Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art) in Winnipeg, MB. Streifler lives and works in Winnipeg on Treaty One territory, the original lands of the Anishanaabeg, Oji-Cree, Dakota, and Dene Nations, and on the National Homeland of the Red River Métis.

Ulrike Veith was born in Germany, and currently lives and photographs in Saskatchewan, Canada. During her career, she has worked as a curator, educator, programmer, administrator, and writer. She has received grants from the German Academic Exchange Service, SK Arts, and the Canada Council. Her work is in the collection of SK Arts. Having started out in the 1980s in analog photography (black & white and Cibachrome), she recently made the switch to digital photography and image creation. Veith is inspired by Imogen Cunningham and Thelma Pepper who

undertook significant photographic projects over the age of 65, in Cunningham’s case over the age of 90 and who shared unique insights into older women’s lives.

Nic Wilson (they/he) is an artist born in the Wolastoqiyik territory known as Fredericton, NB, in 1988. He graduated with a BFA from Mount Allison University, Mi’kmaq territory, in 2012, and an MFA from the University of Regina, Treaty Four Territory, in 2019, where he was a SSHRC graduate fellow. They have shown work across Canada and participated in projects with Remai Modern, Plug In ICA, Art Souterrain, and the Mackenzie Art Gallery. They have shown work internationally with Venice International Performance Art Week, Casa de la Primera Imprenta de América in Mexico City, NADA in Bogotá, and OpenArt In Örebro, Sweden. Working across media, Wilson creates videos, texts, performances and artist books. Their work often engages time, language, queerness, mysticism, decay, and the distance between art practice and literature. In 2021, they were longlisted for the Sobey Art Award. They were the 2022 writer-in-residence for G44 Centre for Contemporary Photography.

Hanna Yokozawa Farquharson is a Saltcoats, Saskatchewan–based artist who moved from Japan to Canada in 2011. Her textile and painted works blend imagery of rural Saskatchewan with the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, reflecting her deep spiritual connection to nature. Rooted in the belief that all elements of the natural world carry spirit, her art seeks peace, joy, and appreciation for life’s ephemeral beauty. In 2024 she debuted as a painter, with work represented by The Black Spruce Gallery. Her practice ranges from contemplative textile pieces to vibrant pop‑art paintings of northern Canadian animals. She was nominated for the 2021 Emerging Artist Award and her solo exhibition toured Saskatchewan with OSAC until 2024. Her pieces appear in private and corporate collections nationally and internationally.

Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall

Media ↑