Image: Hazel Meyer, Muscle Panic objects, 2018. Installed at the Art League Houston, Texas.

Performed with Gee Okonkwo, Mina Silva, Lou Stainback, Evan L. McCarley, and Charli Sol.. Photo credit: Alex Barber

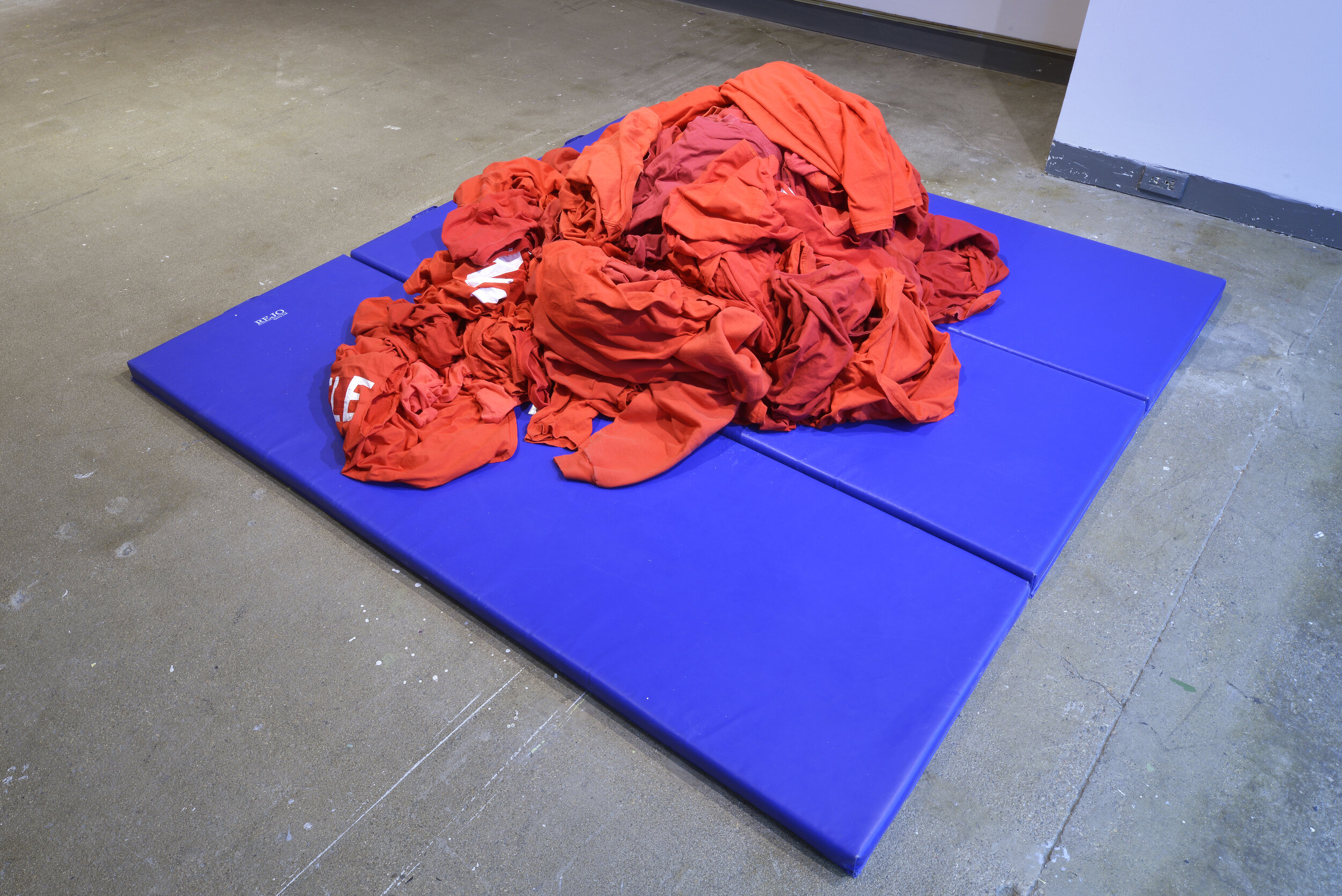

Hazel Meyer’s mutable body of work, Muscle Panic, considers the performance of the athletic. Evoking the imagery of momentous sports history, the bodily gestures and actions of a drill or warmup and the aesthetics of the gymnasium, Meyer instigates an arena of sweat and queer desire. Multiple iterations of Muscle Panic have taken the project from a rogue basketball gym built in an abandoned barn to a clandestine locker room to a warehouse-like gymnastics studio. Simultaneously an installation and a performance, Muscle Panic transforms the banal and austere white cube into a hot physically charged site for emotional and physical exchange.

Essay ↑

By Robin Alex McDonald

Queer theorist Jennifer Doyle suggests that “thinking about sports is like thinking about a novel that has five dimensions. It can be hard to pin down your object. The sport text has watery boundaries: Is it the event? The competition? The broadcast? The arena, fan culture? Training? The match report?”[1] Similarly, thinking about Hazel Meyer’s Muscle Panic is like trying to pin down an immeasurable imagining, one that shape-shifts from idea to archive, from archive to installation, from installation to performance, from performance to print. Each adaptation of Muscle Panic offers new constellations of sport history ephemera, locker room curiosa, and affective objects that reveal the oft-repressed queer and feminist sensibilities of sport cultures: “Sport Dyke” locker labels, a multi-gallon thermos of Lez Hulk Sweat, net-less and bare basketball rims, photographs of women athletes whose tenacity is palpable even on cardstock, a shiny silver whistle around which countless lips have closed. Doyle claims that the athlete’s sense of self is “fluid, changeable, contingent,” but Muscle Panic expands on this to show that the material cultures that constitute the athlete’s world are fluid, too.[2] Their archives take on new shapes and new forms, depending on where and how they are being housed (a gym locker, a storage room, a hall of fame, a gallery) and what their caretaker deems meaningful.

Past iterations of Muscle Panic crescendoed in multi-participant performances that relished the rigor of athletic rituals and the sweet idiosyncrasies of women and queer people occupying space together. In them, Meyer and her team of performers donned handmade jerseys, stretched one another’s bodies, passed basketballs back and forth (and back and forth, and back and forth) between them, inhaled the odour of their own and each others’ armpits, tied their long hair back into sport-ready ponytails, double-knotted each other’s shoelaces. Within the homosocial world of sport, in which teams are segregated by sex and the existence of queer touches, looks, and desires are actively denied, these types of interactions are mostly dismissed as teammate comradery or game-time rituals. In the constructed world of Muscle Panic’s performance, however, these interactions both educe and exceed the intimacies of sex – sweaty touches, heavy breathing, furtive eye contact, giggly asides – and thus speak aloud what Heidi Eng has called the “silences underlying and permeating discourses of normality” within the world of sport.[3]

Named after the sociological concept of moral panic, a fear of something dangerous and threatening to “discourses of normality” as well as the status quo of the social order, Muscle Panic uses touch and sweat to terrorize the gender binary and its attendant presumption of heterosexuality on which most sports rely. Now, in a world where touching, sweating, and breathing together have become dangerous in altogether new ways, Meyer has been tasked with translating the collaborative and spontaneous spirit of performance into another, safer format. For the 2020 version of Muscle Panic, Meyer has solicited five women and/or non-binary athletes to create a collaborative print project that draws from the codes and aesthetics of instructional exercise posters. Such a poster project recalls elementary school gymnasium décor, but it also recalls the safer sex cartoons and information pamphlets created during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s by organizations like the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and the National Coalition of Gay Sexually Transmitted Disease Services, wherein communities disproportionately affected by the epidemic sought to communicate information and care using their own languages and signs. Renowned art historian and political activist Douglas Crimp discussed these instructional comics in his 1987 essay, “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic,” where he referred to community-created materials as “precisely the sort of safe sex education material that has proven to work.”[4] While there are obvious differences between teaching someone how to properly put on a condom and instructing them how to perform the perfect jump shot, there are similarities as well: a flicking motion of the wrist, the need to be gentle yet shrewd, the importance of practice and the risks that sloppiness carries. Both tasks demand focused attention on the body and are usually done in the presence of another body. And if the instructional posters of the 1980s helped gay men to have promiscuity in an epidemic, perhaps this instructional poster can teach its audiences how to create new intimacies in a pandemic by reminding us that the queer desires that exist in sport – the desire to touch, to be playful, to work together in new ways – have not gone away.

Meyer has stated that Muscle Panic is about the need for women’s bodies, queer bodies, and sick bodies to “take up space” on the field, on the court, in the locker rooms, and in the gallery.[5] Now, in the absence of these bodies, we instead have Muscle Panic’s stuff: scaffolding that stands strong like skeletons, pompoms that caress like fingers, the pebbled texture of basketballs like our craggy skin. If, as queer affect scholar Ann Cvetkovich suggests, “objects are meaningful as expressions of desire,”[6] we might think of the objects that make up Muscle Panic as “testimon[ies] to social relations” between an imagined team of women, femmes, queers, crips, and others whose bodies and identities have been, and continue to be, marginalized within sport cultures.[7] Like that stink of sweat that cannot be evicted from a gametime jersey, these relations endure – their affects linger, their politics persist.

Robin Alex McDonald (they/them) is an independent curator, writer, and academic currently living and working as an uninvited guest on Robinson-Huron Treaty territory, the traditional territory of the Anishnaabeg people and specifically, the Nipissing First Nation. Robin works as a part-time faculty member in the Fine and Visual Arts department at Nipissing University in North Bay, an instructor in the Visual and Critical Studies program at OCAD University in Tkaronto/Toronto, and a PhD Candidate in the Cultural Studies Program at Queen’s University in Katarokwi/Kingston, Ontario. Their academic and arts writing has been published in such journals and magazines as Literature and Medicine, Queer Studies in Media and Popular Culture, n.paradoxa, Syphon, nomorepotlucks, Spiffy Moves, and Guts Canadian Feminist Magazine (with Elly Clarke, Amanda Turner-Pohan, and Michelle Ty). To view more of their work, please visit www.robinalexmcdonald.com

[1] Jennifer Doyle, “Introduction: Dirt Off Her Shoulders,” GLQ 19, no. 4 (2013): 423.

[2] Ibid., 426.

[3] Michel Foucault as cited in Heidi Eng, “Queer Athletes and Queering in Sport,” in ed. Jayne Caudwell, Sport, Sexualities and Queer/Theory (Taylor and Francis Group, 2006),

[4] Douglas Crimp, “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic,” October 43 (Winter 1987): 264.

[5] Hazel Meyer, interview for the MacLaren Art Centre, August 2015.

[6] Ann Cvetkovich, “Photographing Objects as Queer Archival Practice,” in eds. Elspeth Brown and Thy Phu, Feeling Photography (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 275.

[7] Ann Cvetkovich, “Personal Effects: The Material Archive of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas’s Domestic Life,” NoMorePotlucks 25 (Winter 2013), no page numbers.

Artist ↑

Installation Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall

Media ↑

Link to Hazel Meyer Muscle Panic Poster Project.

Link to Dunlop Art Gallery or Regina Public Library