Jinny Yu: The world is burning and I am painting

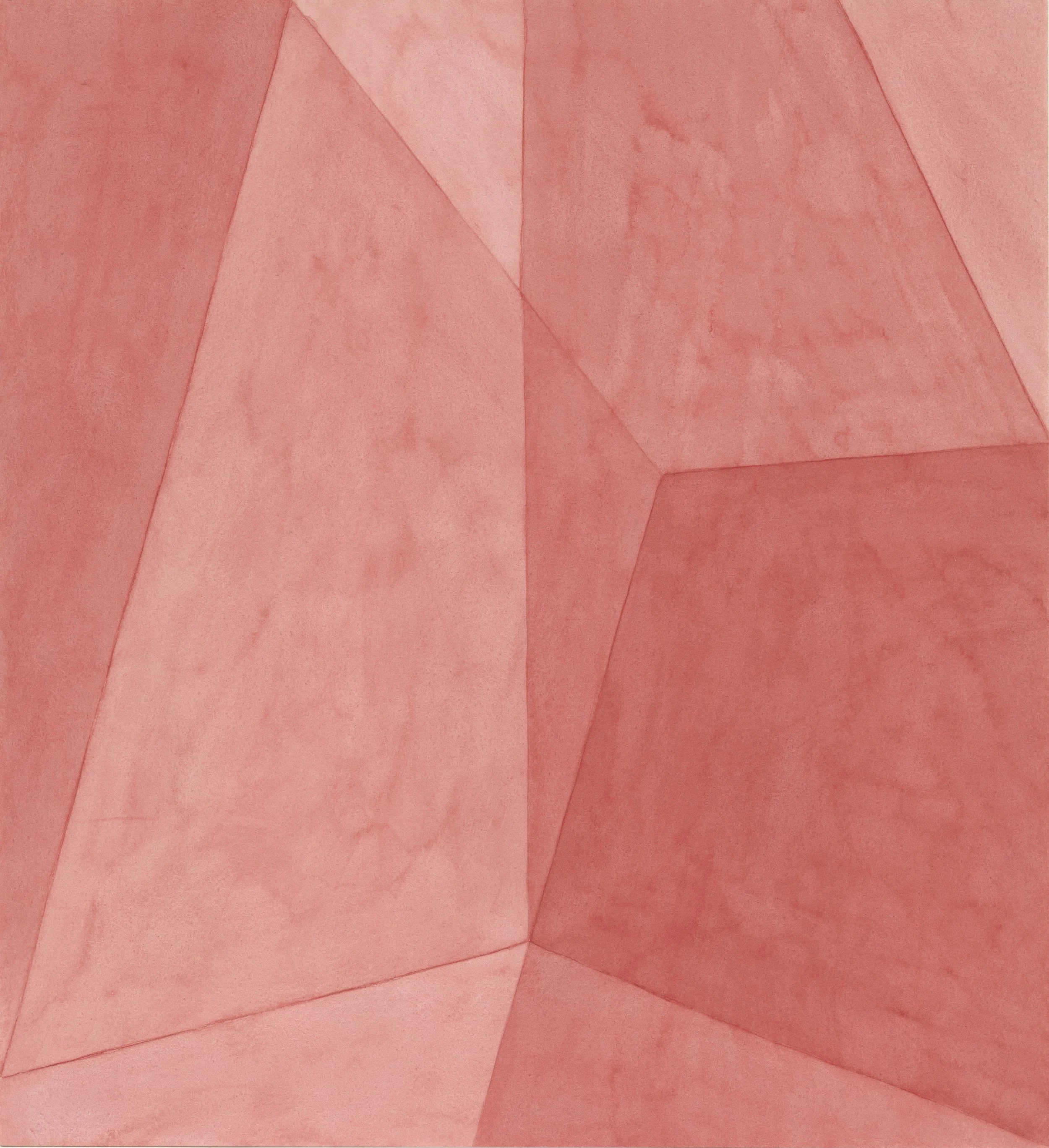

Jinny Yu’s paintings use geometric forms to examine ideas of belonging and place and the shifting roles of guest and host. She creates room-like spaces using cuboid shapes in her abstract work that appear to fold, flip, invert, and reconfigure, offering a visual reminder of how perspectives can change with subtle variations of tone or colour. Having lived in many parts of the world, she shares the complex and personal nature of feeling connected within a place, a concept which is different for everyone and shaped by life experience.

Essay ↑

Inextricably Ours

by Tak Pham

There is solace in Jinny Yu's abstraction. Contemplating colours, shapes, and borders, the artist creates space for reflection in an unpredictable contemporary society that seems to spiral toward complete malfunction with each passing day. In a world of post-truth, deepfakes, artificial intelligence, scammers, tricksters, and charlatans, can abstraction offer relief from the ongoing assaults we're experiencing on multiple fronts?

Central to Yu's artistic investigation is the concept of "host" in the sense of hospitality. Through this inquiry, she examines the complex and shifting relationship between guest and host. Her series Hôte (2020) comprises 42 individual graphite drawings, which were also made into a book. When flipped, the book reveals a black-and-white animation: a black rectangle centred on a white square. As the sequence progresses, the shape shifts and grows until a door slowly emerges, while the surrounding wall transforms from void white to grey hatches at various densities. The final drawing inverts the opening composition—a cacophony of grey noise closing in on a thin white strip at the center of the page. Completed during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hôte marked Yu's first attempt to understand the host-guest relationship through the dynamic between shape and border (Uhlyarik 2024). With the series, she asks: "Can guest host? Can host guest? Guest can host. Host can guest". Or—if I may add—when does guest become host?

In Inextricably Ours (2023), which covers the walls of the Dunlop Art Gallery, Yu pushes this ambiguity further, examining the dangerous slippage between positionalities that assume both power over a domain and the responsibility of care. In his review of the exhibition at its inaugural venue, the Art Gallery of Ontario, critic Earl Miller interprets Yu's exploration of the guest-host relationship as the artist's personal land acknowledgement, "alluding to the position of immigrant settlers on land that does not belong to them" (Miller 2025).

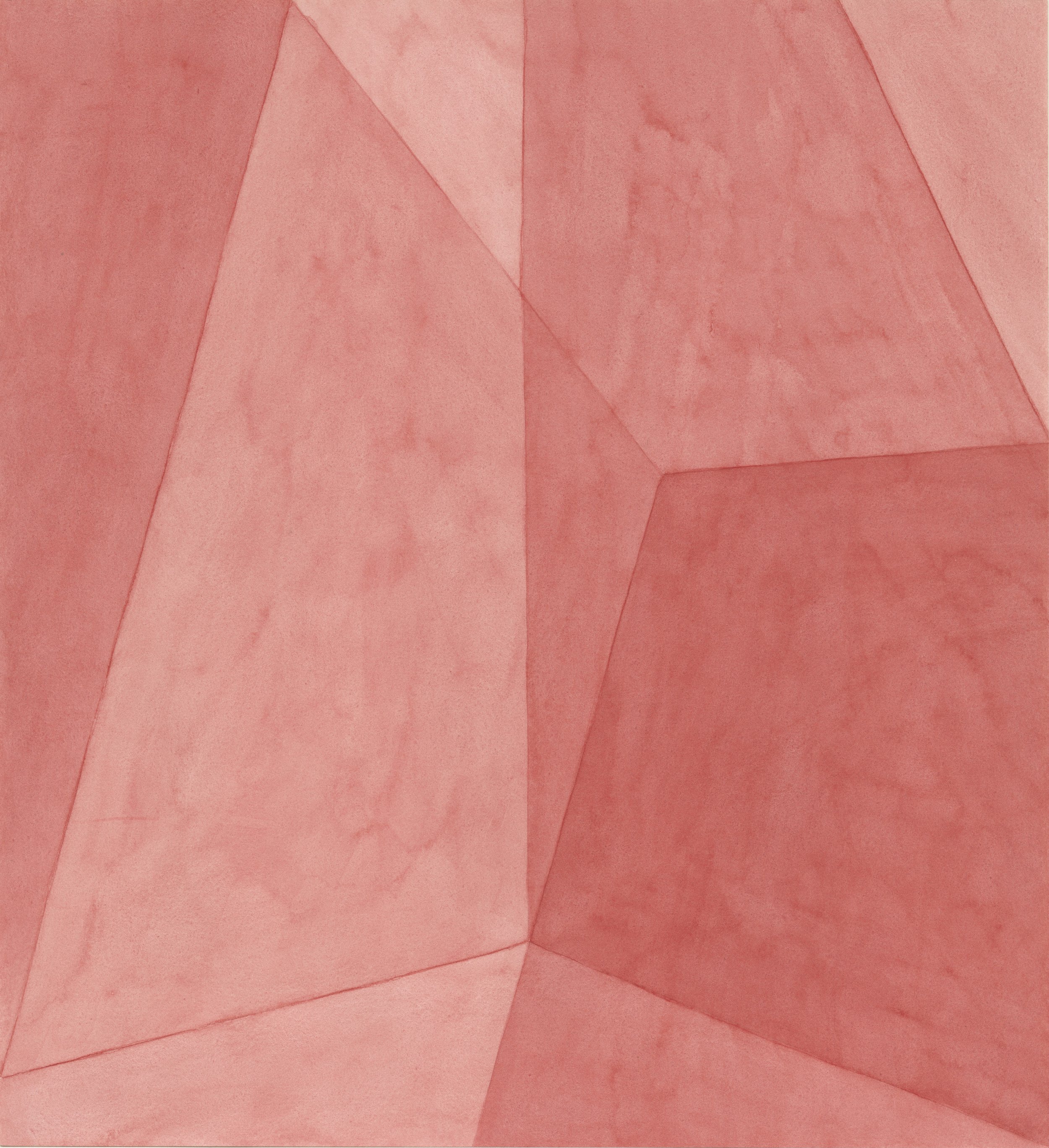

Conceived during a month-long residency in 2022 in southeastern France, the series marked Yu's return to colour after a decade of working exclusively in black. The colourful "wonky cuboids"—as the artist describes them—are Yu's responses to the Mediterranean light surrounding her studio in La Napoule. She used the full range of colours available in the Holbein watercolour set she brought along, allowing hues to interact, slip under one another, and cross over, creating rich and dynamic new tones. As a result, Yu's cuboids are never static. Like the protagonist in Hôte, they are charged with buzzing energy, refusing to conform to the formal constraints of lines and limits.

The Mediterranean Sea that Yu contemplated that April is the same body of water that has witnessed the perils and trials of those who dare to reject borders, escape confinement, and reach for the unknown. The colourful forms in Inextricably Ours, built through laborious layers of mark-making, possess a sublime quality. Like staring into ocean depths where light refracts and shimmers, the cuboids draw viewers closer to the image's surface but never yield to their desire to define the composition. The shapes shift and flee, morph and camouflage, perpetuating the dialectic between the received and the receiver. What remains "inextricably ours" in Yu's painting series is our human pursuit of stasis amid constant flux.

Yu's concern with global migration remains central in her work. In 2015, she presented Don't They Ever Stop Migrating? at Nouva Icona during the 56th Venice Biennale. Inside a room made of soft cotton panels, Yu used ink to create clusters of strokes that, when viewed collectively, evoked a disconcerting and overwhelming sense of “threatening flocks of birds.” To foster an immersive experience, she incorporated a sound collage from Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds (1963), featuring a chorus of female voices asking: "Where did you come from? What are you? What's happening?" Periods of complete silence lasting 40 seconds inserted into the audio heightened the feeling of danger. In the complete stillness, the visitors' minds looped the unseen dialogue, internalizing the fear carried by Hitchcock’s characters. The contrast between "the world opening of the work's visual language and the xenophobia of its aural tonalities" (Tiampo 2024) created a space where the boundary between beauty and threat becomes blurred, allowing visitors to explore their fear of the unknown and broader questions of migration—a nod to curator Okwui Enwezor's theme for the 56th Biennale, "All the World's Future."

Yu's practice offers no easy solutions to the questions it raises. Her shapes resist clear definition, her borders remain permeable, and the relationship between guest and host continuously shifts across her canvases and installations. This refusal to settle into certainty is exactly where the solace lies. In a time when borders are weaponized, identities are policed, and belonging is viewed as a zero-sum game, Yu's abstraction presents a different perspective. Her work in this exhibition at the Dunlop, The world is burning and I am painting, suggests that the instability we fear—the slipping between positions, the difficulty of pinning down what is "ours" and what is "theirs"—may not be something to fix but a state to live in. Through colour, form, and the space between, Yu encourages us to sit with ambiguity, to see that host and guest are not fixed roles but fluid positions we all occupy. In this realization lies the potential for a more generous, more honest understanding of how we share space, resources, and ultimately, ourselves.

Tak Pham is a contemporary art curator and writer. He is currently the Curator of the Illingworth Kerr Gallery at Alberta University of the Arts in Calgary, Treaty 7 territory. He holds an MFA in criticism and curatorial practice from OCAD University. In 2023, he received the Hnatyshyn Foundation-Fogo Island Arts Young Curator Residency. His writings and reviews have appeared in Canadian Art, C Magazine, ESPACE art actuel, esse arts + opinions, Galleries West, The Brooklyn Rail, ArtAsiaPacific, and Hyperallergic.

Works Cited

Miller, Earl. 2025. "Jinny Yu." Border Crossings, January: 145-146.

Tiampo, Ming. 2024. "Jinny Yu: In a World of Binaries, the Pluriversal." In At Once, by Patrick Flores, Ming Tiampo, Georgiana Uhlyarik and Marie-Eve Beaupré, 87-105. Toronto: Goose Lane Editions.

Uhlyarik, Georgiana. 2024. "Jinny Yu is in Between + All at Once." In At Once, by Patrick Flores, Ming Tiampo, Georgiana Uhlyarik and Marie–Eve Beaupré, 15-45. Toronto: Goose Lane Editions.

Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall

Media ↑