Image: Shantel Miller, Stepping Out on Faith, oil on canvas, 2020. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Bodies are complex entities, both built and viewed from many scientific, social, and personal networks. In My Skin brings together artists who dare to self-determine what is means to live in their own bodies. Through diverse feminist perspectives, they resist dominant definitions of how one’s body "should" look, feel, move, and act. Consequently, they embrace the intricacies of what our bodies are and can be. These are acts of resistance and self-reclamation that are actionable calls to respect more fully, love more completely, and care more intentionally for the bodies we inhabit and, by extension, those of others.

ESSAY ↑

It’s not meant to be beautiful ̶ it’s meant to be real.

By Thirza Cuthand

We all live in these fleshy houses for souls, and the exhibition In My Skin reveals how each artist confronts, loves, tattoos, reconstructs, and represents bodies. Regardless of if we consent or not, our bodies become political sites, or as Barbara Kruger said, “Your body is a battleground.” The wars fought over the body are often just as colonial as wars fought over land. People have attempted to erase Trans, Black, Indigenous people, Women, in favour of a cis het white supremacist patriarchy.

Living in a body which challenges that system can be challenging. Currently a site of conflict is coming from transphobic politicians and children’s authors who have nothing less than genocidal aims towards the Trans community. This has also been found in certain more conservative TERF Lesbian communities who have tried to pretend Trans Women are not also part of Lesbian history and culture. In Jaye Kovach’s DYKE, a photo shows the artist’s receding hairline with the word DYKE proudly tattooed into her skin. A Butch Trans Woman, Jaye’s work is confrontational in the best ways. Her eyes stare back at you in works like Truck Nutz, where a gleaming gold pair of testicles commonly found on the back bumpers of Trucks in Saskatchewan hangs between her breasts. Trans people are often asked inappropriate questions about their bodies. This particular pair of nuts, while in other circumstances might speak about a cloying masculinity, instead helps us consider gendering nuts differently. Could they be glamorous, feminine nuts? Context is everything.

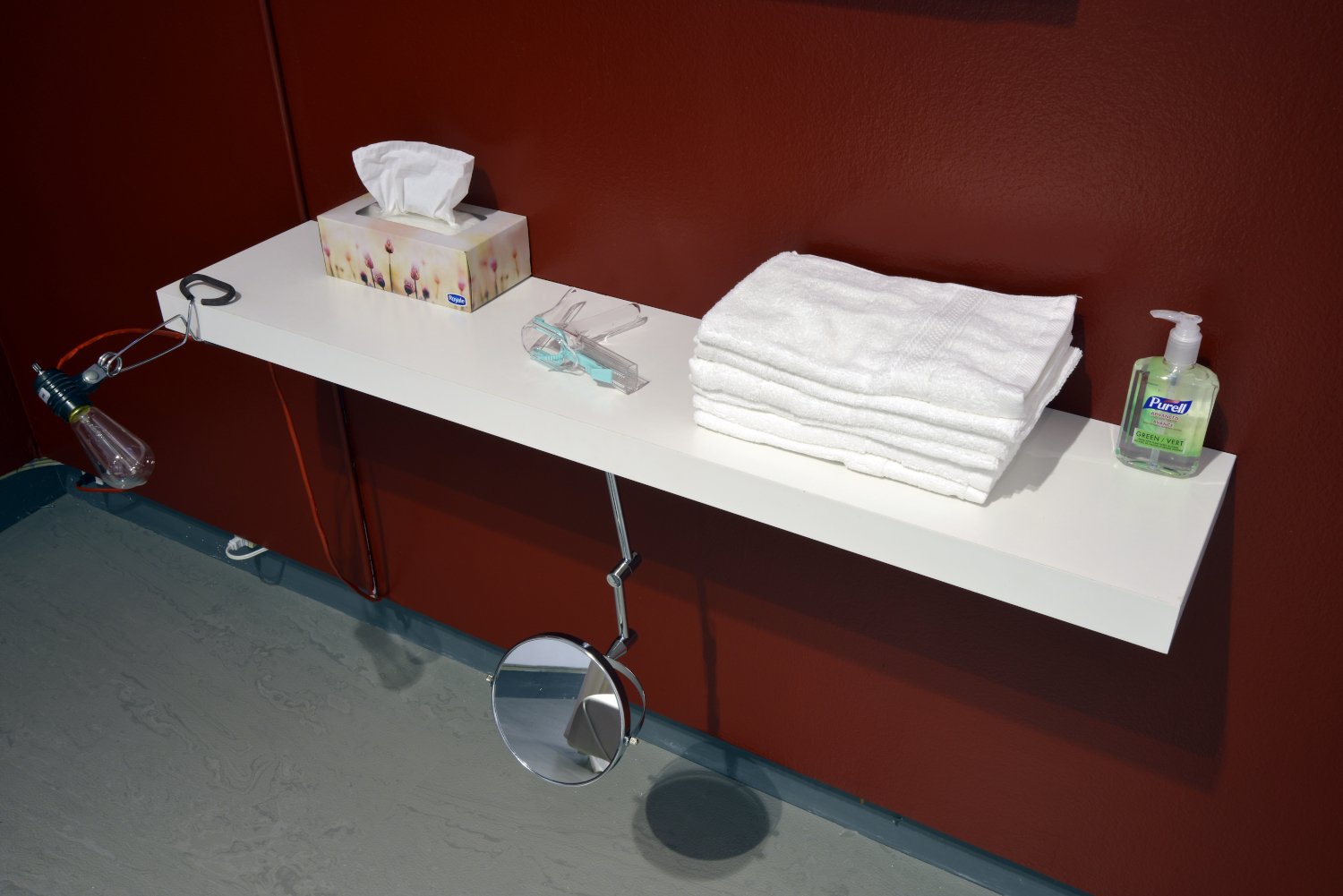

Vanessa Dion Fletcher’s “Inside Voices” displays the artist’s menstruating cervix on video. Cervixes are not easily seen in everyday life, but her zine demonstrates how to view your own cervix. Cervix exploration in art and people’s lives have had a long feminist history, including in Annie Sprinkle’s Public Cervix Announcement performance where she showed her cervix to an audience and answered questions about it. “Inside Voices” complicates the cervix viewing with a discussion of reproductive health and the financial cost of creating babies with assistance. As a Lenape woman, Vanessa’s nod to reproductive health is not only about a woman’s self-determination to reproduce or not, but Indigenous women’s self-determination over their reproductive health in a genocidal health care system.

Shantel Miller’s “Stepping Out” series is an elegant series of doors opening for a single Black person’s leg beginning a journey out of the safety of home into the world. They wear no shoes, socks, pants, or dress. The nakedness of their leg is nevertheless not yet vulnerable in these images since the rest of the presumably nude person’s body is still hidden in shadow. A protective darkness from which they are emerging. “Stepping Out (Stefan)” shows a long muscular leg, while “Stepping Out on Faith” hints at a profound moment of leaving one worldview to embrace something new. Their third work, “Doorways”, shows a woman deciding between two doors, one white and one black, choosing which world to enter.

Dayna Danger’s “Big ‘Un’s,” a series of glistening naked women and non-binary people holding Big Game skulls complete with huge horns and antlers, plays with the dual meaning of Rack. Rack of antler/horns, Rack of breasts. Horns and antlers are often used in competition between two rival suitors for the ability to be chosen by a desired mate. Human breasts have also been decorated, presented, showcased, and sometimes hidden, or bound, in order to attract or repel potential lovers. The variations of areola colours in the models are also present in the background of each image. The models aren’t passive however, the truly impressive horns or antlers they each hold speak of power, and a certain queerness in regards to covering their genitals with such masculine symbols.

Riisa Gundesen’s work touches on mental health crises and how they manifest corporeally with skin picking, scratches, and discarded mess around her. Her roughly painted figures and objects confront the viewer with moments imagined as private. A toilet with menstrual blood in it, a woman climbing out of the wall with a face mask, flesh upon flesh reaching out or pushing inward into the space. It’s not meant to be beautiful ̶ it’s meant to be real.

Zoë Schneider’s “Grotesque” pairs an abundantly fleshy fat suited figure, a representation of the artist, surrounded by foam “breads.” The interplay of fat embodiment with a flaunting of carbohydrates challenges fatphobic biases that soak contemporary society. Carbs are demonized in a number of popular diets as being responsible for fatness. Meanwhile they are a source of comfort and joy. Schneider’s “Grotesque” doesn’t show a beautified fat body, the face is rough and fleshy and abstract.

Ella Cooper’s “Embodied Land Ecstatic” has at its root, the concept of Black Joy and elation. Black female nude figures are leaping into the air in typical Canadian wilderness images, no context is given for their actions. The scale of the landscape imagery is the type that typical Canadian images are made of, large rocky ledges, snow, pine trees, and mountains. The figures experiencing joy aren’t dressed for the weather, bringing to mind popular Canadian activities like Polar Bear Swims which test participants ability to withstand the freezing water of lakes and oceans. They also seem almost suspended in mid-air in a dreamlike state. The freedom to be naked and in wild spaces also speaks to a sense of joy which comes with safety.

The works in In My Skin are a challenging ride through representation. A thread connecting a lot of the works was a sense of humour about the bodies we have been given to live in and think about. Opening up to the work in this exhibition taught me a lot about the unconscious feelings I still feel about my own Fat, Trans, Queer, Indigenous, body. I have this strange balance between wanting to feel sexy and wanting to be honest and not worry about judgements. In My Skin takes the pressure off needing to always be a beautiful object, and into the experience of joy and comfort in being a person with flaws and that’s ok.

Thirza Jean Cuthand (b. 1978 Regina SK) makes videos, films, and performance art, about sexuality, madness, Queer identity, love, and Indigeneity, which have screened in festivals and galleries internationally. They completed their BFA majoring in Film/Video at ECUAD in 2005, and their MA in Media Production at X University in 2015. She is a Whitney Biennial 2019 artist. He is Plains Cree/Scots, a member of Little Pine First Nation, and resides in Toronto, Canada.

Installation Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall

Media ↑

Feeding the Trolls: The Bait and Switch in Zoë Schneider’s Grotesque in the Grotto, Christine Negus, BlackFlash, 2022.