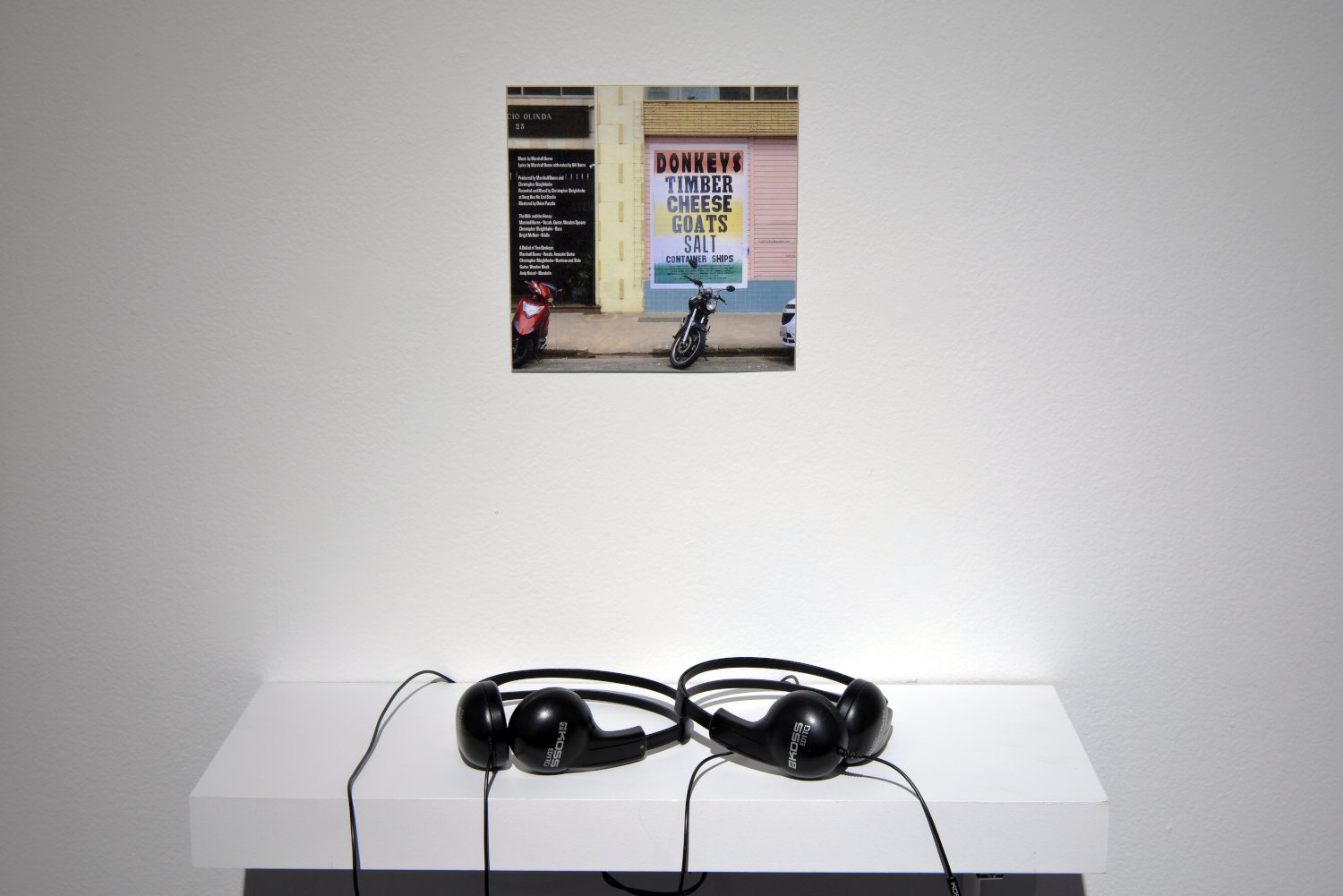

Image: Donkeys, Cheese, Timber, Goats, Salt in Sao Paulo, Installation, 2020. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

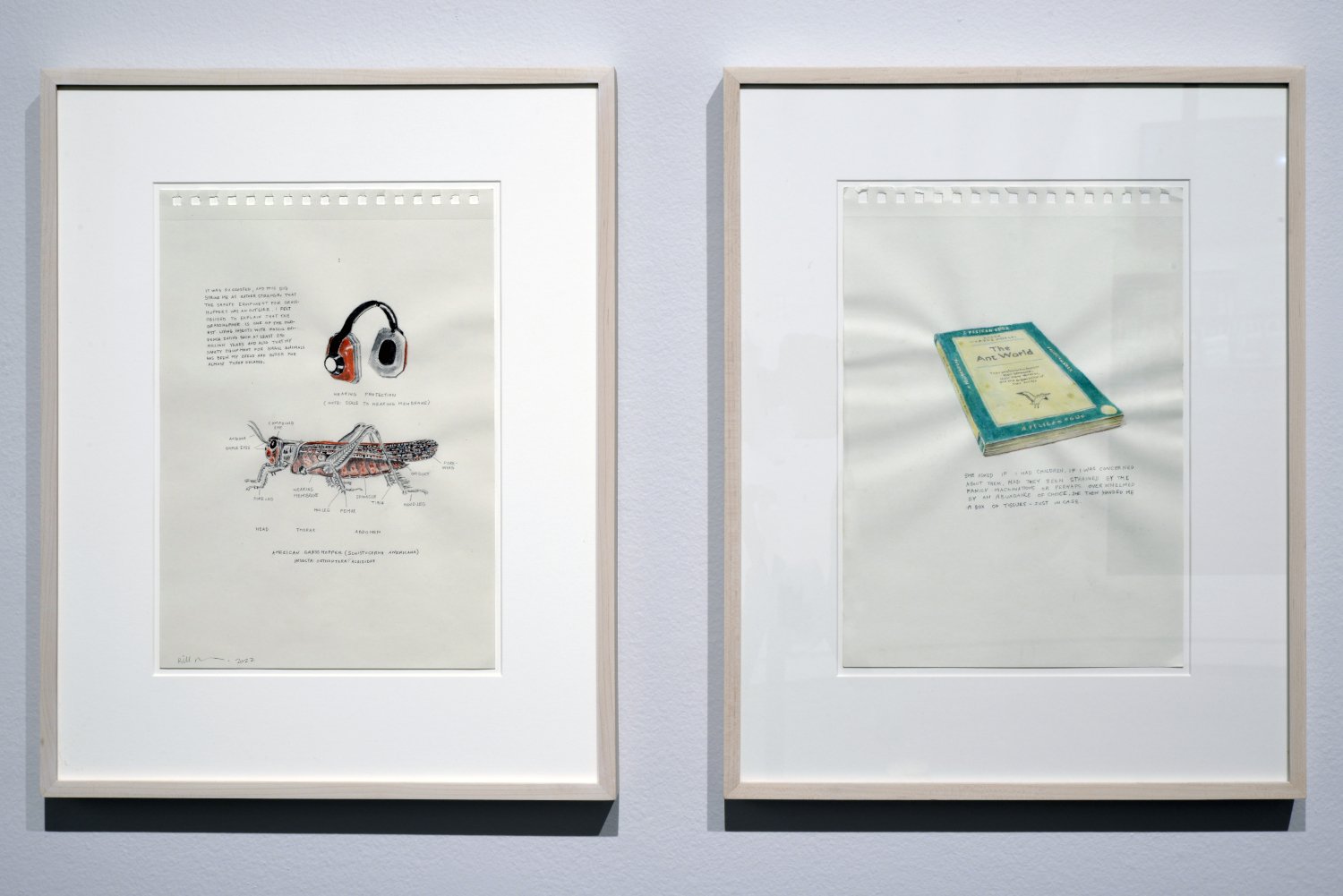

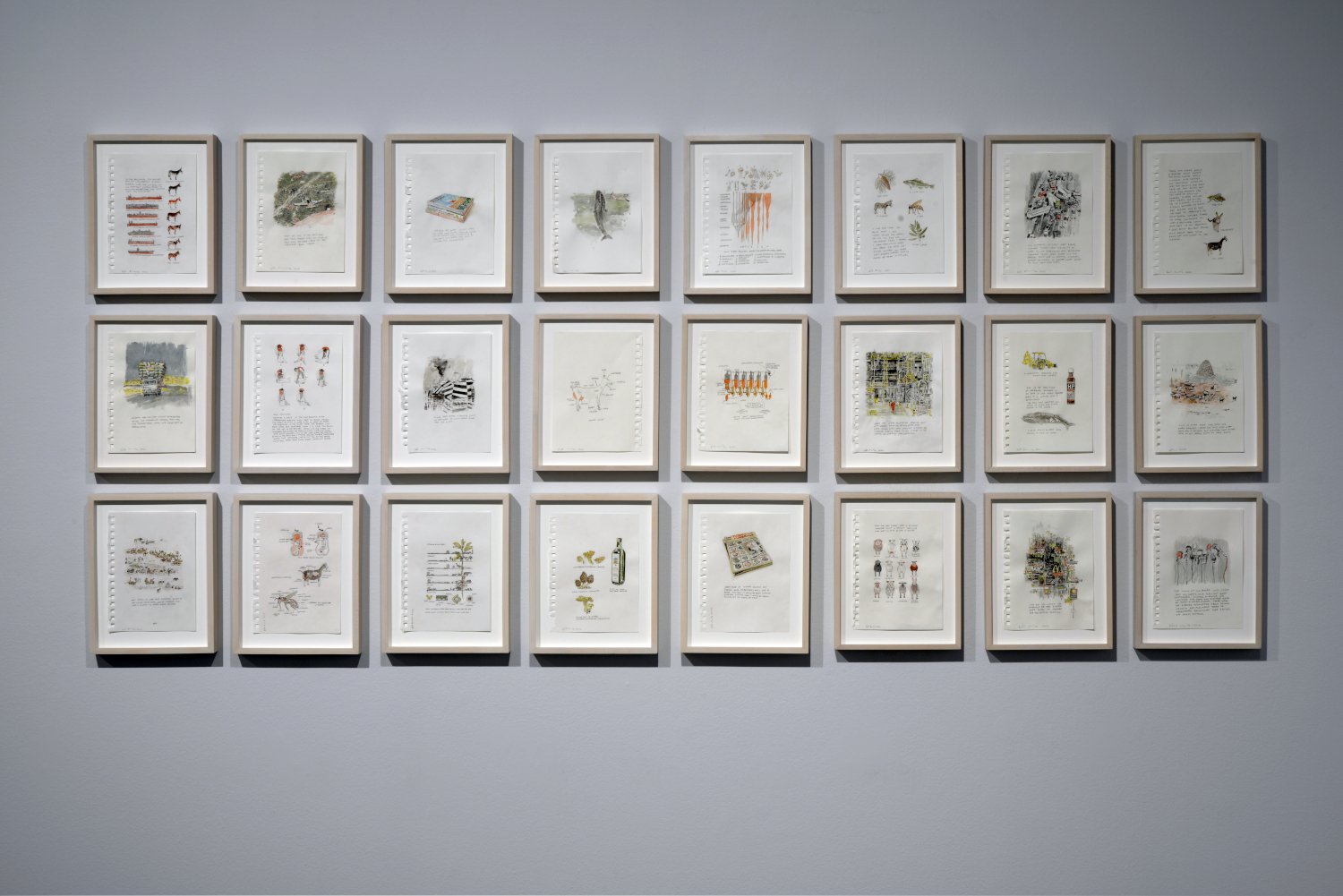

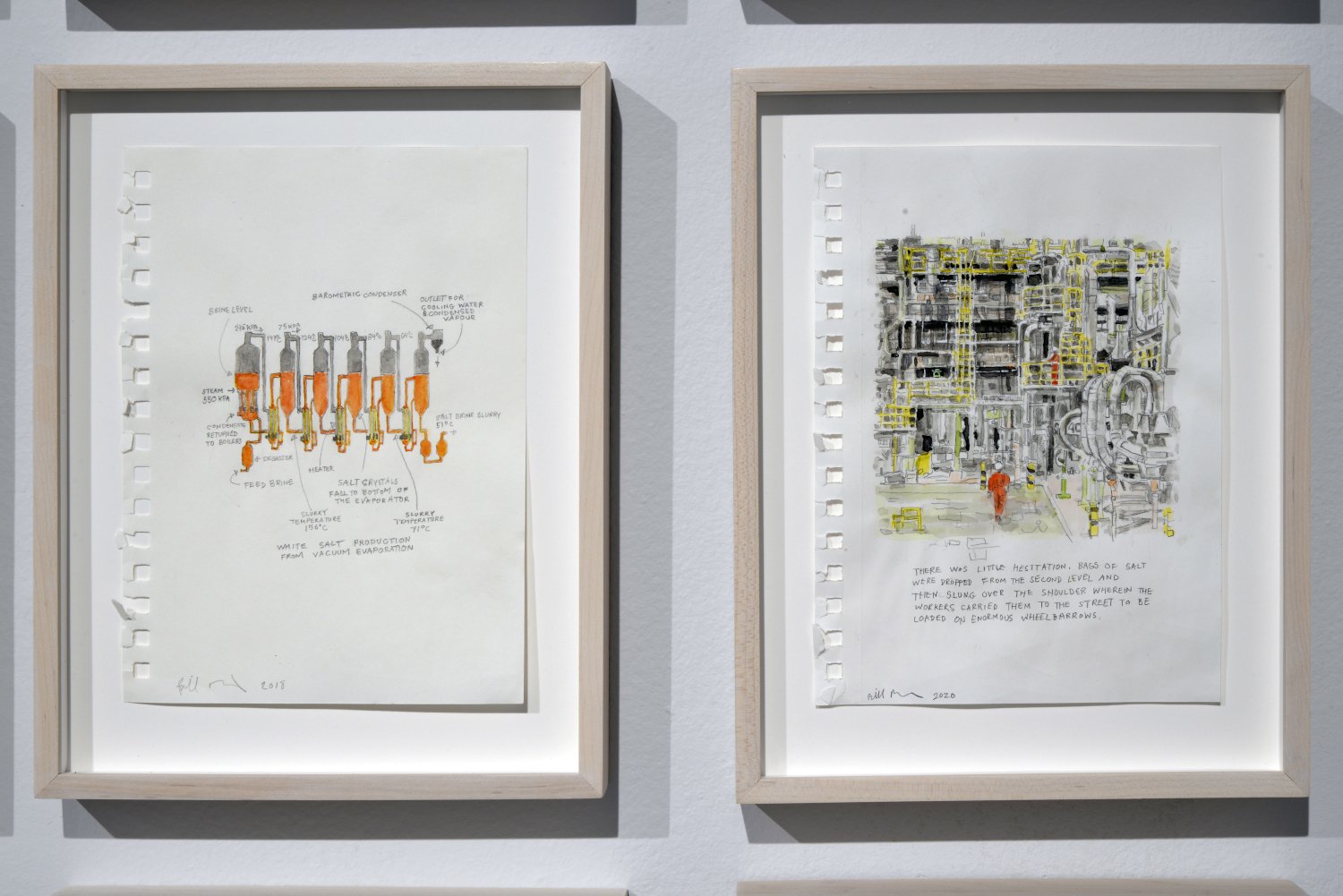

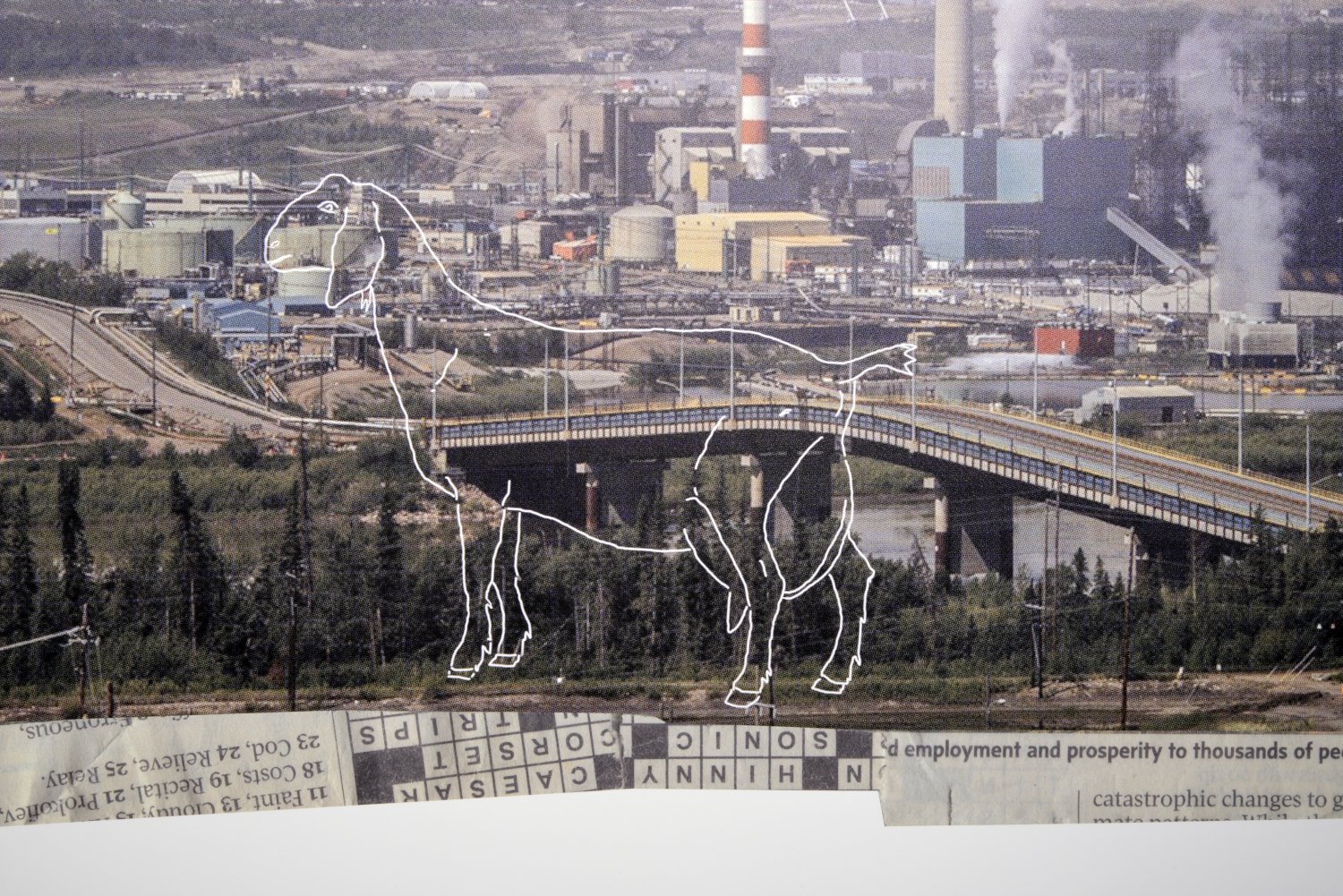

The Salt, the Milk, the Donkey, the Honey, the Folk Singers is part of an ongoing series of work about global trade, food production, and advanced industrialism and has been presented at various locations throughout the world. These images, drawings and installations continue his interest in connected global patterns of production, trade and sustainability, articulated through the embodied connections he builds between individuals and the more-than-human world.

Accompanying this exhibition, a live performance will take place on July 2, 2022, with the support of the Regina Farmers Market. The performance includes a procession of musicians, goats, farmers, beekeepers and a donkey.

Salt, The Milk, The Donkey, The Honey, The Folk Singers, The Vinyl Record is available for sale at Regina Public Library, Central Library, 2311 12th Avenue, Regina, SK or at SaskBooks. Music by Marshall Burns, Lyrics by Marshall Burns with notes from Bill Burns.

Artist ↑

Bill Burns

ESSAY ↑

The export, the load, the price, the gift, the magic.

By Jody Berland

You are walking through a tree shaded path and you encounter a donkey on parade. “On parade” sounds noisy, but this is a quiet walk of people and animals approaching as though lifted from a time far, far away and long ago. The walk is enchanting, with music, donkeys and goats, their caretakers, cooking appliances, and people preparing to sing when they reach their destination.

This is not just any donkey. This is a beautiful donkey, calm and charismatic, with an amiable face and soft fur. Everyone wants to scratch the animal’s head, although this is not a planned part of this special occasion, with its ritualistic inclusion of singing and salt. The donkey is like a celebrity, with staff hovering nearby and people lining up for a closer look. People are starved for this kind of contact with an animal that is so unfamiliar, yet so ordinary that its presence seems like magic. The donkey is a gift, reminding us that families used to gift each other precious animals in the context of their particular rituals of the time.

While I am overwhelmed with the desire to pet the donkey, it is not a pet (to conjugate from noun to verb) but a working animal. The donkey’s work is of a cultural nature. Its job is to perform being a donkey in human settings such as movies and parades. I have been following the work of Bill Burns for some time, but this is the first time I have petted a donkey. The connection travels from my hands to the tendrils of memory I have of that day.

. . . .

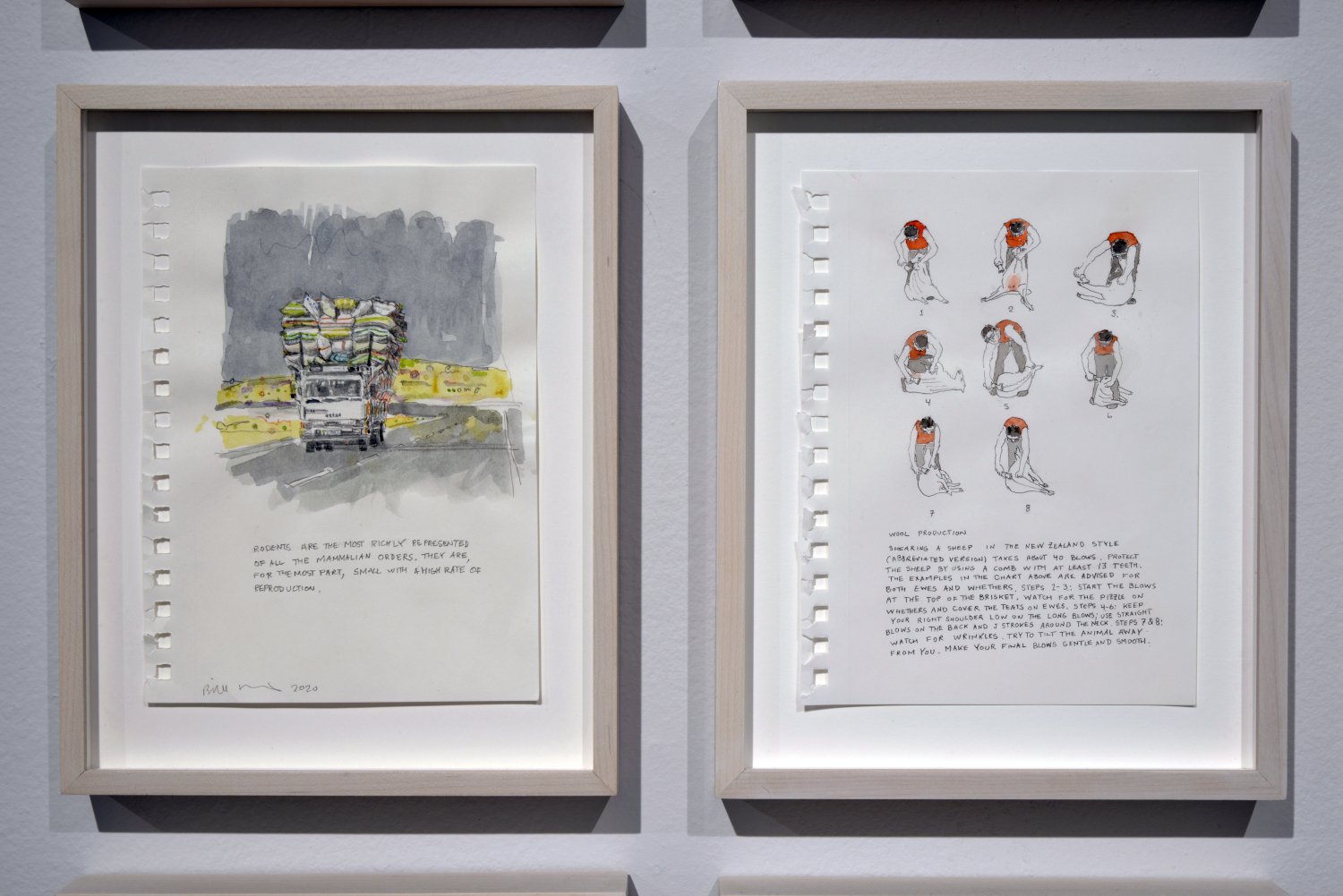

Sheep are very fragile. Care is of utmost importance when in transit. Especially when shipping by sea. This advice is illustrated by exquisite colour pencil drawings of healthy specimens of twelve breeds of sheep, eleven of them facing the viewer and standing on all four legs.

Bill is not a sketchy sort of person, so the fine detailing and use of pencil is deliberate. It occurs to me that the artist has taken more care with these drawings than the animal welfare inspectors are likely to take with the sheep being prepared for transport across the sea. It is not as though we wouldn’t respond to other kinds of images, especially if they show such enchanting animals. These drawings draw us into their space in a special way. They are small yet commanding invitations to contemplate how animals come to us and how we encounter other species on whom we rely in this late industrial age. The drawings also remind me that it is too soon to talk about a (post)industrial age. There is nothing post-industrial about the transport of animals, but there is something non-industrial and perhaps anti-industrial about these drawings. Industry is dedicated to producing the most profit, in the least amount of time. In that respect they have stolen words like “industry,” the way we might use it to describe the patient labours of a donkey or a bee. These drawings are a gift because they are the other way around.

I wonder if the same attention to detail would be found among the inspectors responsible for assuring the health and wellbeing of sheep bound for ocean travel. I investigate. 1 They talk about the “suitability and practicality of animal welfare measures” but they don’t mean, suitable to the sheep. If Bill Burns’ drawings of animal transport convey a language of calmness and attention to detail – not too much detail, just enough that you see them for what they are – the language in which scientists discuss the advice Bill poses in his drawing of twelve sheep provides detail of a different type. The animals are numbered, locations and minutes are numbered, video clips are measured, and the action is recorded entirely in the passive voice. No “we,” no “they.” There is no trace of living, feeling, sentient creatures but they are moving by so fast it’s hard to say. They don’t have time to pause to have their portraits taken. The transport of animals and people to the New World was built on a callous calculation of life in relation to death, time, efficiency, and profit. The animals and animal parts shown on these paper drawings are small, gleaming fragments of life floating through and away from such calculations. These drawings are so gentle they don’t seem to belong in the same lexicon, but they remind us of the world in which lives become commodities as they suffer the ships, boats and trains conveying them around the planet. Please, the sheep say to us, and the fish, and the bees, and the donkeys: pay attention.

. . . .

These works are miniatures of large and vibrant lives and ideas. Animals have always been traded between humans. They are so central to human social life that most ancient coins featured animals etched into their surfaces, reminders of the moment before when people traded live animals for food, wives, or other kinds of riches. Canada’s first coin was inscribed with the image of the beaver. The etymology of salary is salt. Bill’s drawing of an overloaded truck reminds us that rodents still accompany the passage of our food stores from one place to another. There are probably rodents on the cargo ships waiting for the sheep to have their fear measured and approved by experts. It used to be the custom to bring cats on ships to help control the rats and mice that accompanied the grain being shipped by sea. When Bill travelled in Argentina or Mexico, he would see trucks so overloaded with grain or rice that they landed in the ditch. “Rodents like rats and mice are very successful animals,” Bill says, “and they eat our leftovers and are able to get into our food stores. I've put them (the truck, the grains, the rats and mice) together here since they share a social life with us in cities, on farms.“

As we work, animals work with us; as we move, animals move with us; as we eat, animals eat and are eaten. Animals also eat other animals, and we feed animals to the animals we live with, our companion species, Donna Haraway calls them, who dine on the bodies of cows and pigs and sheep and fish who are raised to feed us and our pets. Cats must miss their quarry; they bring their owners the bodies of mice or birds they have killed as gifts or tributes, the way our ancestors gifted a couple of goats or cows or chickens. We are alienated from those food animals, not only because we live in cities, but also because the lives of most animals are spent being caged or shipped or processed by machines.

. . . .

Bill writes that his ideas about trade came out of his experience with Elders in the North. He told me that the gift of caribou meat got him thinking about how our economic transactions work, and how “this gift of meat was different than many transactions or exchanges I had experienced.” The gift cannot be quantified. The vision of the caribou meat prepared for guests is deeply and quietly fortifying, but it is also disturbing, because they are disappearing. Bill’s drawings have a similar kind of affect. They attentively observe and mediate the relationships we have created with sheep, bees, rodents, donkeys, and giraffes, and they trouble our entrapment in the world of global commodity exchange that joins and separates us at the same time.

In a recent book, I wrote about the “Emperor’s giraffe” sent from Benghal to China in 1414 as a tribute dedicated to future trade. The boat and the giraffe were one gesture, one offering, each needing the other to perform their mission. Bill’s drawings, like his earlier “safety gear for small animals,” invoke need in a different way. Tracing the movement of animals that surround, nurture and die for us, these drawings are both reserved, like the whisper of a life drawn in another life, and painstaking, like winding a clock, sharpening a pencil, encountering a donkey in a city park. They hint at intimate moments of creation tempered with wrath and sorrow.

Writing about his earlier work on the “Great Curators of the World,” curators Jennifer Matotek and Stuart Reid wrote, “Bill Burns asks the viewer to contemplate what we value, why we value it, and what it is we truly long for.” 2 Bill’s work reminds us that what we long for is complicated and that we need to pay closer attention to it. Donkeys are not endangered by extinction, while giraffes are one of the species we wish to save. Petting them is a luxury, a potlatch of cross species love we could live without, but saving them is a different matter. Bees are a species we must save. We long for harmonious relations with sentient animals, near or distant, whose live bodies and the products derived from them circulate like blood and water through our lives. The global trade that moves these animals towards and away from us began with ancient commodities like salt or sheep. Today, Windsor Salt has been purchased by a

multinational conglomerate and animal agriculture is owned and dominated by a small number of very large corporations. Our encounters with salt or sheep, donkeys or giraffes, and the ways we feel about them, are negotiated across these complicated histories and infrastructures. They aren’t always in the passive voice. Each look, each touch, each gift, each drawing joins us with the fabric of these connections.

1 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2021.687162/full]

2 Jer Zielinski, TOPIA 39, 29, utpjournals.press/doi/ pdf/10.3138/topia.39.br11

Jody Berland is a professor of humanities at York University in Toronto. Her research and teaching involve interdisciplinary explorations of technologically mediated encounters with music, time and space, animals, and nature. Her latest book, Virtual Menageries: Animals as Mediators in Network Cultures (MIT Press and Leonardo Books, 2019), addresses the widespread use of animals as emissaries in colonial and contemporary visual, digital and musical culture. Her current work concerns media representations of nonhuman life in the age of risk. The team engaged with this SSHRCfunded project has produced an art exhibition, you can access the catalogue for Digital Animalities: the Exhibition, via PublicJournal.ca. She is also a musician, editor, and former resident of Regina.

http://www.arts.yorku.ca/huma/ jberland/

Installation Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall