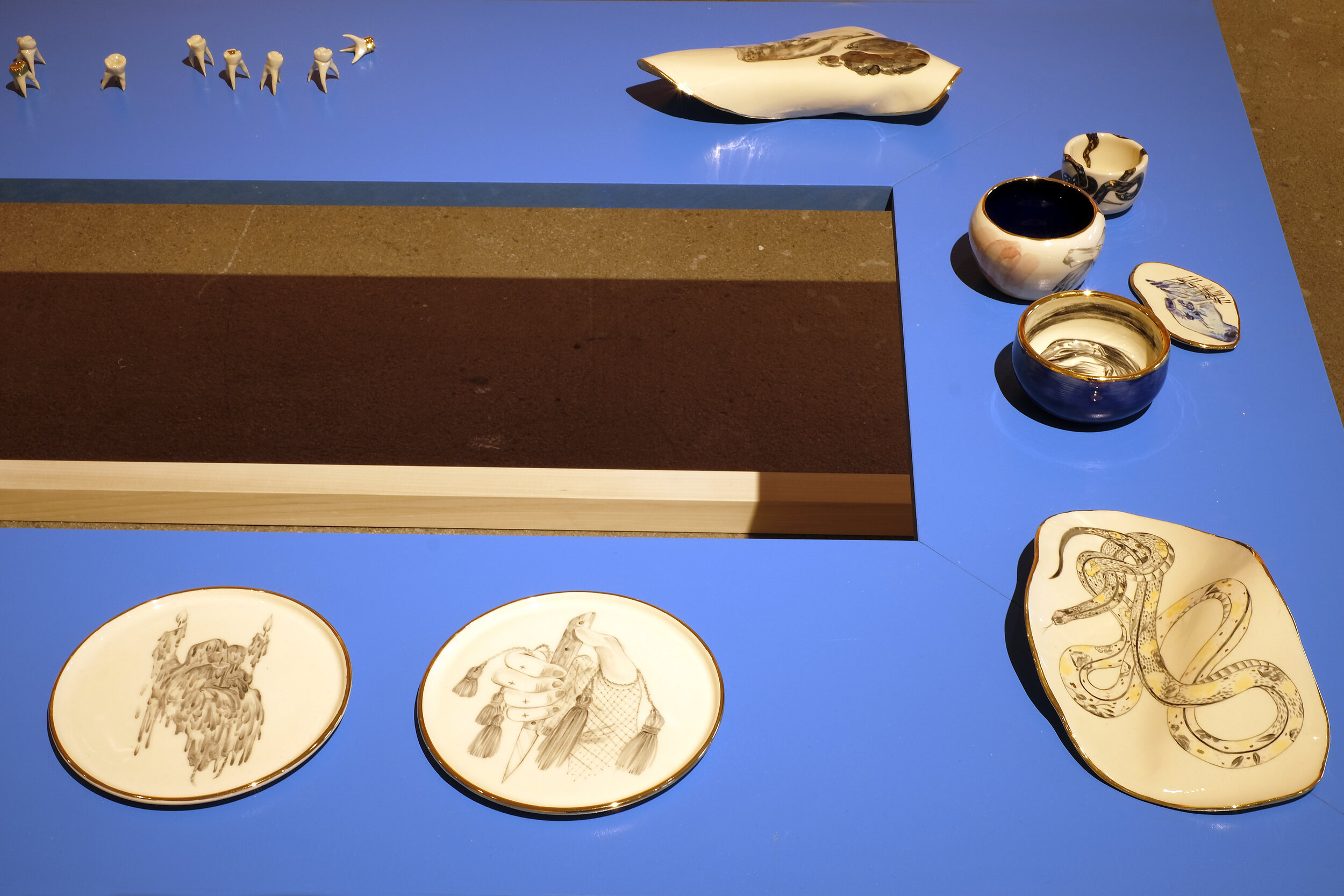

Marigold Santos, MALIGINTO , glazed ceramic, 2019. Photo: Don Hall

Marigold Santos’ practice explores the ways in which ideas of self-hood can become multiple, fragmented, and dislocated and then reinvented and recreated through a reflection of movement, migration and change. In particular, she returns to the memories associated with her family’s immigration from the Philippines to Canada in the late 80’s as an auto-biographical point of departure, and considers the experiences of a young person coming to terms with a new sense of self in relation to their new environment. Negotiating narratives of the past and present results in the creation of a personal myth, a visual vocabulary influenced by the hybrid of Filipino and Western folktales of Santos' early youth, the Canadian pop culture of the late 80’s and early 90’s, the science and social politics of that period, and the Canadian geography and landscape.

The imagery within Santos' interdisciplinary work consists of elements that reflect on the notion of a self that is plural and in-process, and takes place within the realms of the otherworldly - where the porous boundaries of reality and the fantastical rupture, overflow, and reconfigure. Persistent in her work is the reference to the creature of fear in Filipino folklore known as the Asuang - a supernatural shape-shifting witch and ghoul who has the ability to self-sever. In her work the narrative is reconfigured; these Asuang speak not of malevolence, but of lived experience, self-awareness, transformation, and empowerment to celebrate and embrace plurality and fragmented identities.

Artist ↑

Transmutation and Diasporic Subjectivity in Marigold Santos’ MALAGINTO

By Marissa Largo

In the video installation GOLD WOMAN, a larger-than-life plaster cast of a large female figure lies upon a pyre of rocks in Alberta. She is set ablaze. Over the duration of the 26-minute single shot accompanied by a ghostly soundtrack of the blowing wind, her body is consumed by fire and is destroyed before our eyes. Marigold Santos’ poem graces the walls in both English and in her mother tongue of Tagalog:

The gold woman lies here

in flame and smoke

while she slowing transforms

into the dust of our ancestors

which we mark our skin with.

Ang gintong babae ay namamalagi ditto

sa apoy at usok

habang siya ay dahan-dahan na nagbabago

sa alabok ng ating mga ninuno na kung saan

namin markahan ang aming balat.

Transmutation, the change of state from one substance to another, may be likened to a sort of alchemic process that diasporic subjects undertake as they uproot and reground. Just as the golden woman transmutes into smoldering ashes, so too does the diasporic subject engage in cultural reconfigurations to adapt to their new context. As the artist suggests in her poem, the evisceration of the golden woman is not a diasporic loss, but is a gain, as the ancestors are carried into the present.

Santos’ production arises from her diasporic consciousness. The artist immigrated to Canada from the Philippines as a child in 1988. She mines her cultural influences and the supernatural to signify a multiplicity that exceeds categories, borders, and normative worldviews. Her central motif is her reinvention of the asuang, a self-severing vampiric witch from Philippine folklore. Herminia Meñez believes that the vilified asuang is the result of a “colonial encounter” between 16th to 19th century Spanish missionaries and the babaylanes, the female shamans who had powerful roles in the pre-Christian Philippines. [i] Many babaylanes were heroic leaders, had access to magical powers, and were knowledgeable in medicine and midwifery. The missionaries inverted the powerful and life-giving attributes of the baylan and demonized her as the viscera-sucker. By adopting Catholicism, one could incapacitate an asuang; holy water, a crucifix, and the priest’s cincture (belt) could prevent her from self-segmenting and taking flight.[ii] By transforming the babaylanes into harbingers of death, the colonial mission in the Philippines subverted Indigenous feminine power.

GOLD WOMAN, and the many other depictions of asuangs in MALAGINTO, iterate the ways in which diasporic consciousness exceeds colonial logics and optics. In her analysis of the works of Filipino American artist Manual Ocampo, Sarita See (2009) argues that the disarticulation of Filipino bodies in his work is a response to the erasure of Filipino/a subjects within the US empire. Not only does “disarticulate” refer to the dismemberment in his often-gruesome images, but it has the dual meaning of “disrupt the logic of.”[i] Similarly, Santos’ disarticulated asuangs and the destruction of the golden woman refuse assimilation and thus, disrupt colonial logics through their multiplicity and decolonial recuperations.

GOLD WOMAN is equally influenced by the iconic biblical figure of Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonian king whose dream of the obliteration of a huge idol of gold, silver, bronze, iron and clay foresaw the rise and fall of nations. In the book of Jeremiah, Nebuchadnezzar’s ambitions for an eternal empire were smitten by divine powers. Santos’ rich multi-archival references speak to the limits of the nation – a kind of futile golden idol – within diasporic imagination.

Further, Santos’ depictions of asuangs on the ceramic pieces in this exhibition offer us ways to think about the limits of visibility as empowerment. While their faces are obscured or shrouded, the figures have their bodies revealed. Faint lines across their torsos remind us of their uncanny ability to self-disarticulate. Like the demonized prophetess, diasporic Filipinx subjectivity is subjected to colonial and heteropatriarchical optics. With their supernatural bodies unabashedly exposed, the asuangs’ refusal to return the gaze is an act of feminist self-representation that weilds power through choice.

Pottery, like the body, can be thought of as a vessel. The clay works in MALAGINTO are not your quotidian vases or dishes. Many pieces evade symmetry, are non-functional, and like the asuang’s body, are severed, fragmented, and imperfect. For Santos, who is also tattoo artist, both skin and clay are porous surfaces for mark-making. As clay becomes vitrified through fire, her glazed imagery becomes fixed, much like a healed ink-filled puncture wound that becomes living art – both processes of transmutation. Santos’ transmutations are “the dust of our ancestors which we mark our skin with.”

The alchemic visualities of MALAGINTO unsettle colonial legacies and present us with diasporic imaginaries that demand reckoning.

Marissa Largo, PhD is a researcher, artist, curator, and educator. Marissa's manuscript, Unsettling Imaginaries: The Decolonial Diaspora Aesthetics of Four Contemporary Filipinx Visual Artists in Canada will be the first book on Filipinx Canadian art. Her projects have been presented in venues and events across Canada, including A Space Gallery (2012 and 2017), Open Gallery of OCAD University (2015), Royal Ontario Museum (2015), WorldPride Toronto (2014), Nuit Blanche (2009, 2012, and 2019) and MAI (Montréal, arts interculturels) (2017).

[1] Herminia Meñez, Explorations in Philippine Folklore (Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1996), 89.

[2] Ibid., 90.

[3] Sarita See, The Decolonized Eye: Filipino American Art and Performance (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), xviii.

Installation Images ↑

Photos: Don Hall