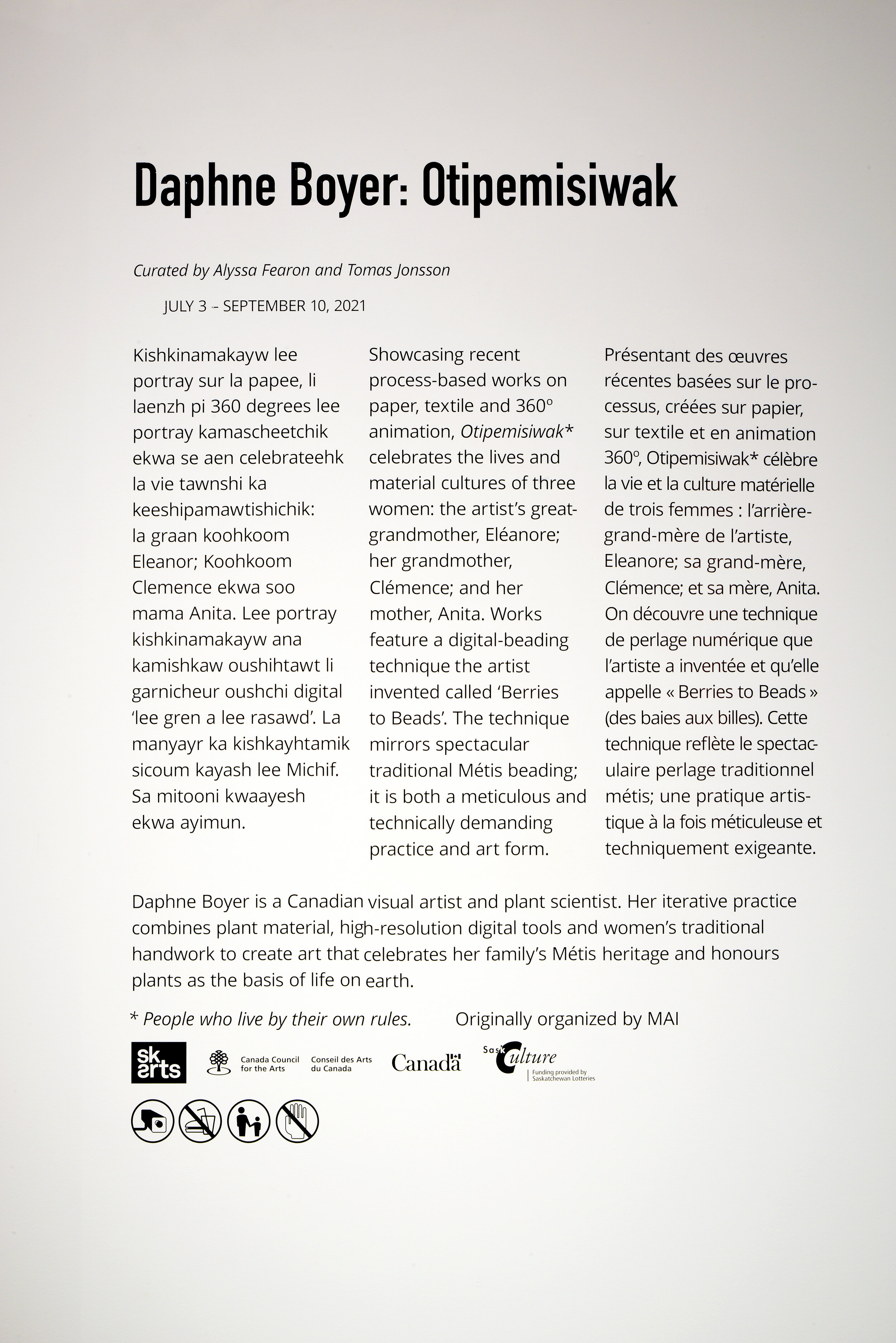

Image: Daphne Boyer, Barn Owl and Moon, 2019, digital collage of photographed berries. Pigmented ink on Canson rag paper. Laser-cut owl and moon. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Daphne Boyer: Otipemisiwak

Curated by Alyssa Fearon, Director/Curator and Tomas Jonsson, Curator of Moving Image and Performance.

Kishkinamakayw lee portray sur la papee, li laenzh pi 360 degrees lee portray kamascheetchik ekwa se aen celebrateehk la vie tawnshi ka keeshipamawtishichik: la graan koohkoom Eleanor; Koohkoom Clemence ekwa soo mama Anita. Lee portray kishkinamakayw ana kamishkaw oushihtawt li garnicheur oushchi digital ‘lee gren a lee rasawd’. La manyayr ka kishkayhtamik sicoum kayash lee Michif. Sa mitooni kwaayesh ekwa ayimun.

Showcasing recent process-based works on paper, textile and 360º animation, Otipemisiwak* celebrates the lives and material cultures of three women: the artist’s great-grandmother, Eléanore; her grandmother, Clémence; and her mother, Anita. Works feature a digital-beading technique the artist invented called ‘Berries to Beads’. The technique mirrors spectacular traditional Métis beading; it is both a meticulous and technically demanding practice and art form.

Présentant des œuvres récentes basées sur le processus, créées sur papier, sur textile et en animation 360º, Otipemisiwak* célèbre la vie et la culture matérielle de trois femmes : l’arrière-grand-mère de l’artiste, Eléanore; sa grand-mère, Clémence; et sa mère, Anita. On découvre une technique de perlage numérique que l’artiste a inventée et qu’elle appelle « Berries to Beads » (des baies aux billes). Cette technique reflète le spectaculaire perlage traditionnel métis; une pratique artistique à la fois méticuleuse et techniquement exigeante.

Daphne Boyer is a Canadian visual artist and plant scientist. Her iterative practice combines plant material, high-resolution digital tools and women’s traditional handwork to create art that celebrates her family’s Métis heritage and honours plants as the basis of life on earth.

* People who live by their own rules.

Originally organized by MAI

Artist ↑

ESSAY ↑

Seeds of Connection

By Warren Cariou

In Daphne Boyer’s art, everything is more than what it seems. Digital imaging is embedded in the analog richness of plant materials; icons reverberate with stories; discrete elements of each work form new meanings within a network of relations. Inspired by the artist’s life-long devotion to plants, these works reflect a gardener’s eye for design and a herbalist’s knowledge of the ways in which plants can be our allies. The works also draw from centuries’ old traditions of Métis material culture, especially the distinctive flower-beadwork patterns that have carried Métis plant knowledge for generations. The artist routes these traditions through the transforming conduit of digital imaging to create new ways of understanding our relationships to the land and to one another – human and beyond.

These works have even more meanings for me personally, because Daphne is my first cousin, the daughter of my brilliant and beloved Aunt Anita, who was one of my favourite storytellers in our family of splendid raconteurs. My understanding of Daphne’s art is inevitably influenced by the family stories, relationships and memories we’ve shared throughout our lives, and I am grateful for this opportunity to reflect on the ways this work resonates with my own experience and preoccupations. While our shared family connection may give me an idiosyncratic point of view on these works, I think this is also very appropriate because they are all, in one way or another, about kinship connections.

This focus on kinship is clear in “All My Relations,” which is dedicated to the artist’s late mother Anita. Daphne’s arrangement of simple iconic images throughout this mural perfectly represents the circularity of Aunt Anita’s storytelling style, as well as her love of the plants and animals of the prairies. The imagery of vehicles--including canoes, Red River carts, and 1970s-style cars–represents the theme of movement in our family’s history, dating back to the fur trade, as relatives traveled in search of work and then traveled again to reconnect with kin. As the title suggests, the artist’s relations in this mural are also the plants and animals themselves, reflecting the ethic of reciprocity that is a key element of Métis teachings. While there are no human figures depicted in Daphne Boyer’s work, the human presence is always visible in that sense of our kinship with the other beings of the natural world.

The use of natural materials is most noticeable in “Poison Ivy and Thorns” and “Hung Out to Dry,” both of which are constructed out of digital photographs of leaves. The first of these shows poison ivy leaves stitched together with hawthorns and cut into the shape of a tipi cover, something like the buffalo hide tipi coverings of an earlier era. The digital medium enables an element of fantasy here, since these actual leaves would not be large or strong enough to cover a tipi, but the result poses a suggestive question: how could this famously toxic plant be crafted into a shelter, a home? Perhaps we can learn something from poison ivy, which protects itself from harm by exuding its irritants onto anyone who mistreats it. This image, then, is about survival, about creating a home that is safe in a world that threatens all kinds of harm.

“Hung Out to Dry” also references harm, though it may at first appear to be a quiet domestic image, with its beautiful strips of circular leaf cut-outs attached to a line by clothespins. But when we realize that these splashes of colour are created from photos of maple leaves–the quintessential symbol of Canadian nationhood–then the title of the work takes on a different meaning. In the late 19th century, the Métis nation was indeed hung out to dry by the fledgling state of Canada, which sought to establish itself in the west through the violent suppression of Métis rights. This reached a crescendo in Canada’s attack on Batoche and the subsequent execution of Louis Riel–by hanging. In that light, these bright discs of maple leaf hanging down from the line resemble nothing so much as dried blood, wounds only partially healed since 1885.

“Barn Owl and Moon” and “Moss Bag” are two examples of Daphne’s Berries to Beads process, in which thousands of digital images of berries are arranged in patterns like traditional Métis beadwork. I love how this process literalizes the name of the “seed beads” that have played such an important role in Métis material culture. In both works, one major difference from traditional beadwork is scale. Printing these images in a large format allows the viewer to recognize the “seeds” within the beads, and to contemplate the ways that traditional beadwork is connected to practises of plant harvesting, preservation and consumption.

Daphne’s refiguring of traditional Métis craftwork continues in “For Clémence,” which involves concentric rings of gigantic, brightly coloured porcupine quills. This gestures to the rare tradition of Métis artists who use dyed quills to create adornment on moccasins and clothing. In the mural, the circular arrangement of these quills also evokes the iris of the human eye–an unchangeable part of us, unique as a fingerprint. All of this creates a fitting tribute to our larger-than-life grandmother Clémence, whom we grandchildren alternately feared and adored. It was only later that we understood why Grandma was such an imposing character. Growing up in the shadow of 1885, she faced decades of hardship and discrimination that taught her the lesson of the porcupine: protect yourself and your own by turning inward, becoming prickly.

Despite this, Grandma could never stop herself from taking joy in the simple, sensual pleasures of life, and I believe she had an artist’s heart, hidden beneath the prickles. She played harmonica with abandon, she made rag rugs, she knitted everything from slippers to blankets to footstools. Her preferred medium was a polypropylene yarn called Phentex: brilliantly coloured, inexpensive and absolutely indestructible. Many of her knitted productions are still in use today, including the pincushion I keep on my writing desk as a memento. I am struck by the way it echoes the digital quillwork of my cousin’s dazzling intergenerational homage. “For Clémence” reminds me that Grandma is still with us in so many ways. She would smile to know that she inspired such a bold and resonant design.

Grandma Clémence’s pincushion. Photo by Warren Cariou.

Installation Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall