Essay ↑

Kway Kiishkwihk

Wuskiixaskwal waak Waapsowihleewi Niipaahum

neewaanihka

niish tawsun waak takwiinaxke waak ngwuta

April 15, 2021

Dear Logan,

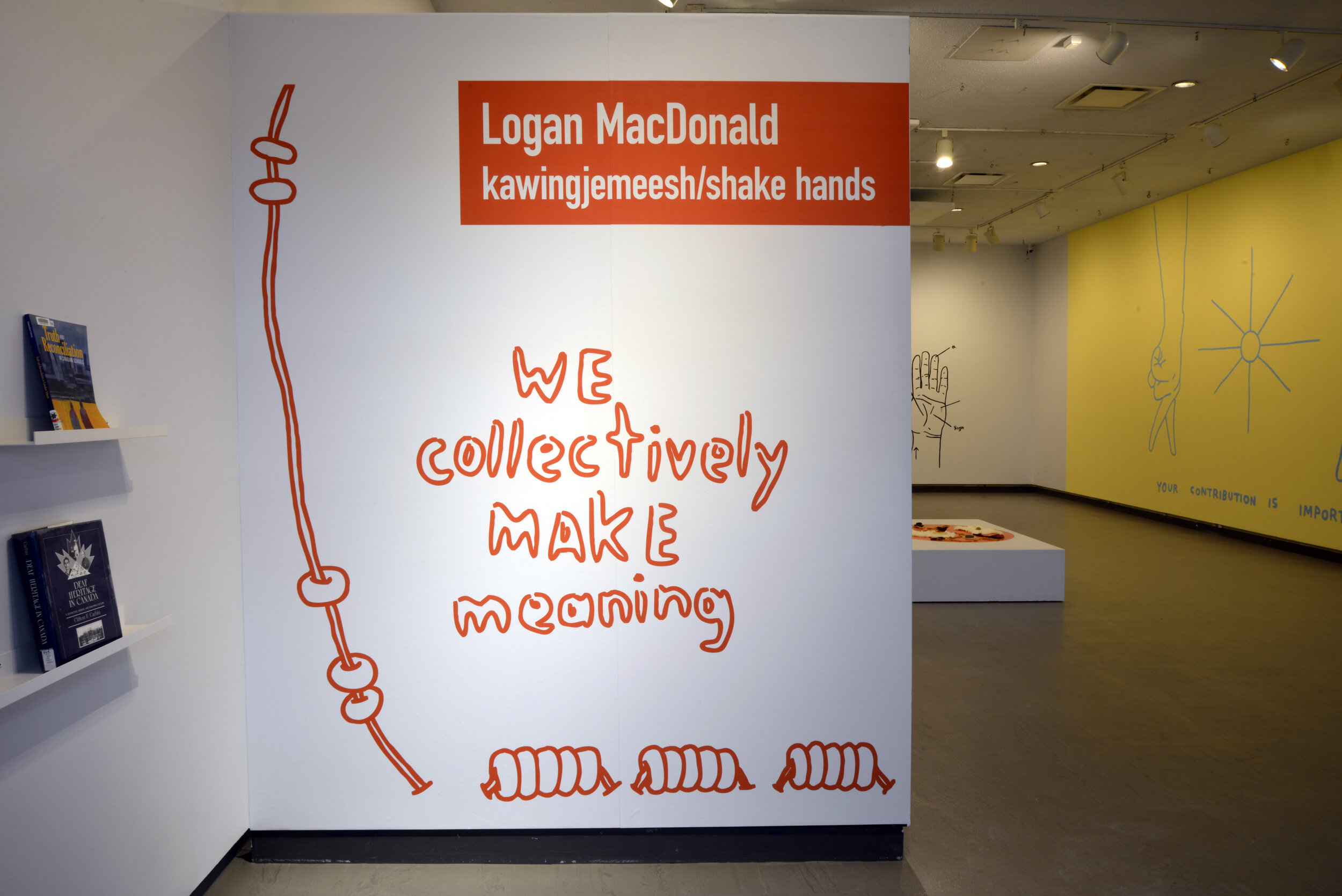

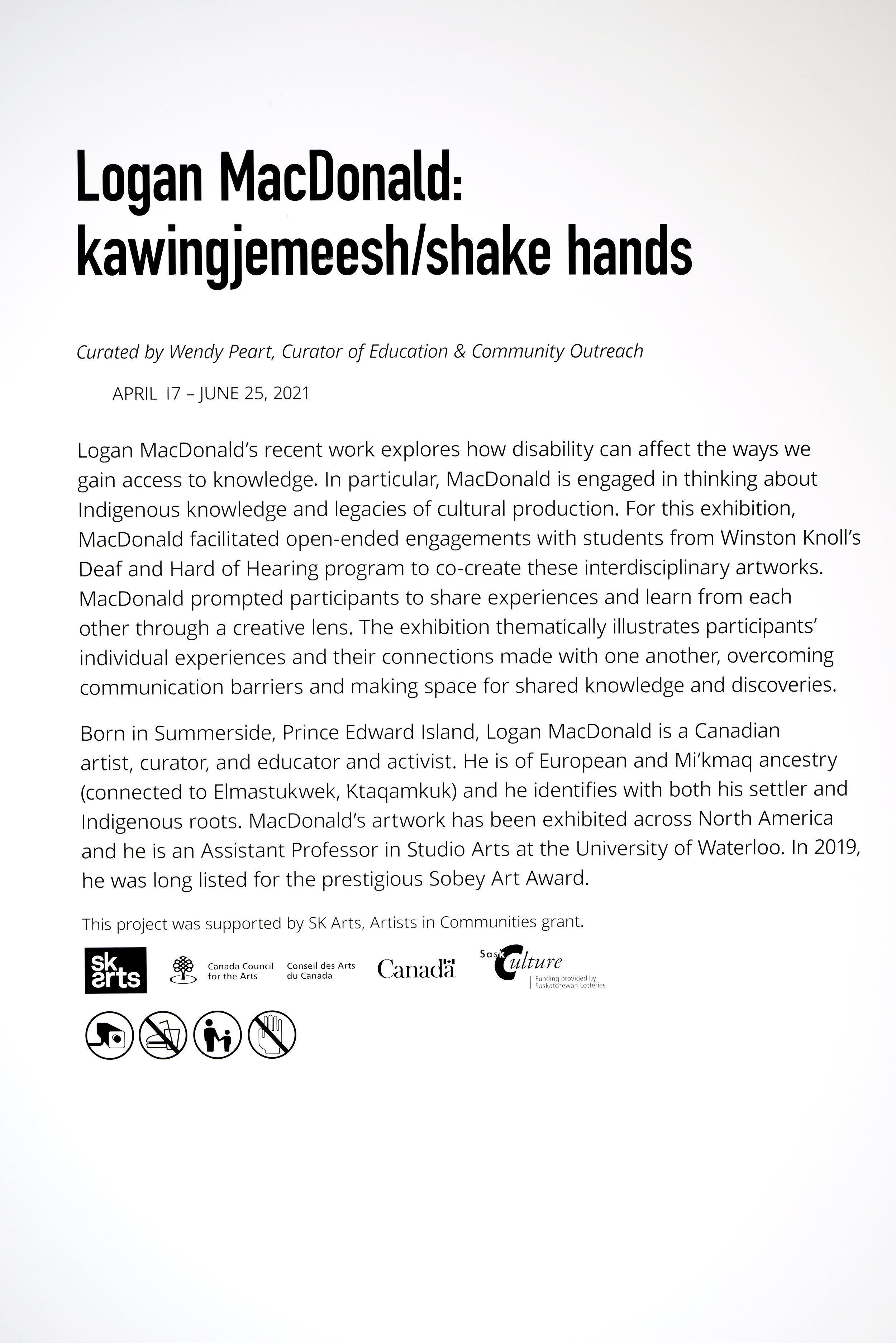

It has been such a pleasure to get a glimpse into your project with the Dunlop Art Gallery and Winston Knoll's Deaf and Hard of Hearing program. I love working as an artist because there are often opportunities to share our skills with communities that we might not otherwise be able to connect to. I am not currently part of the Deaf or Hard of Hearing community. However, hearing loss runs in my family, and I know that I fit into a "normal" range of hearing right now but that it won't always be the case. I am grateful that my experience as a person with a learning disability/neurodiversity within the visual arts has led me to get to know and work with you and other Deaf and Hard of Hearing artists. I enjoyed the stories you shared about working with the students, their passion for making, interests and community. Projects like these are interesting and tricky to identify where the art is. Is it a kind of relational aesthetic? A community art practice? Research? You have described these drawings as letters to the students.

When I think about art and disability and accessibility, I think about the multitude of ways that people are creative. One of the most exciting parts about studying art at school was learning that there are so many ways to express oneself. Western art history is full of people experimenting challenging and manipulating those boundaries. These ideas of what is defined as art get even more hard to define when we think about art outside of the western canon.

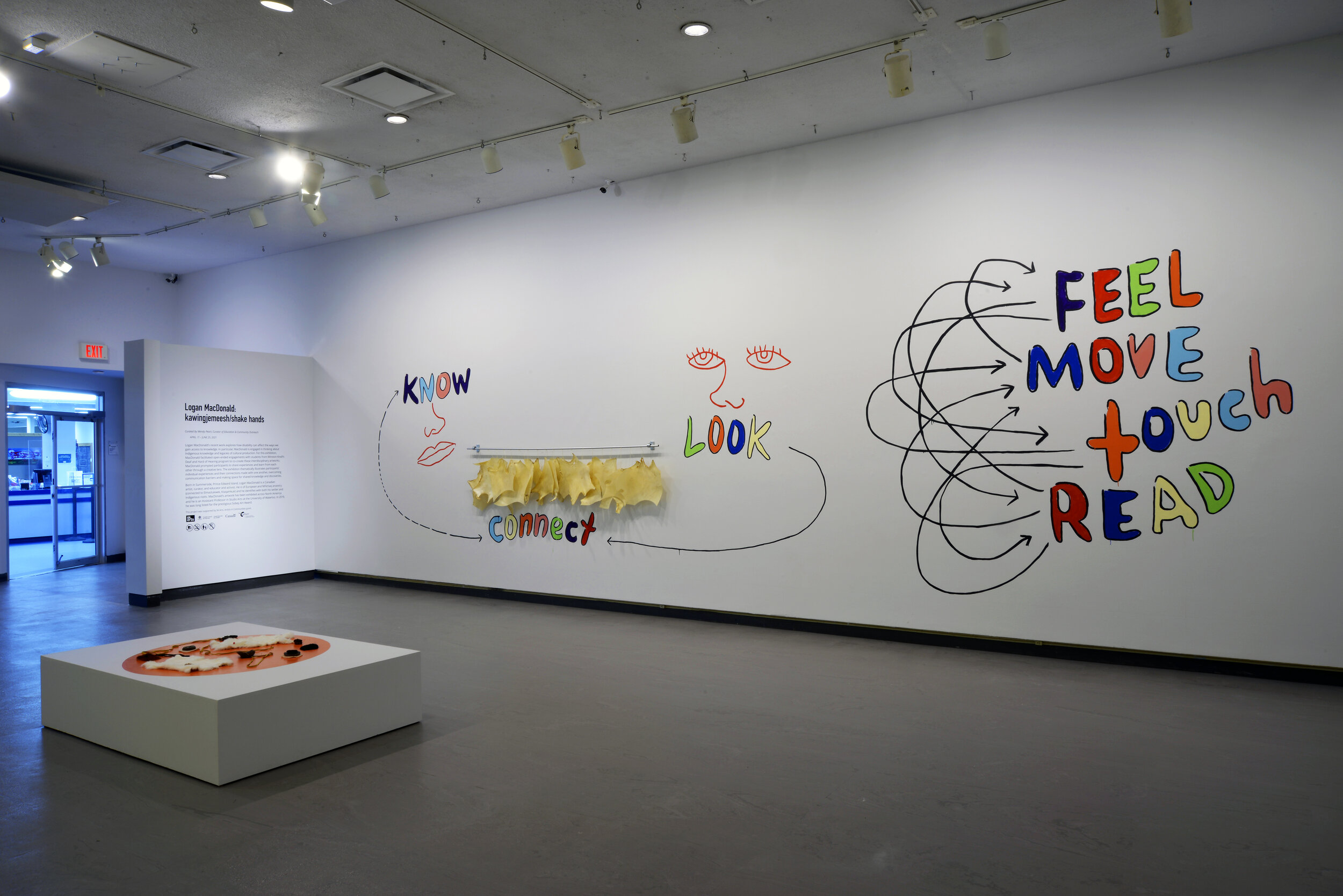

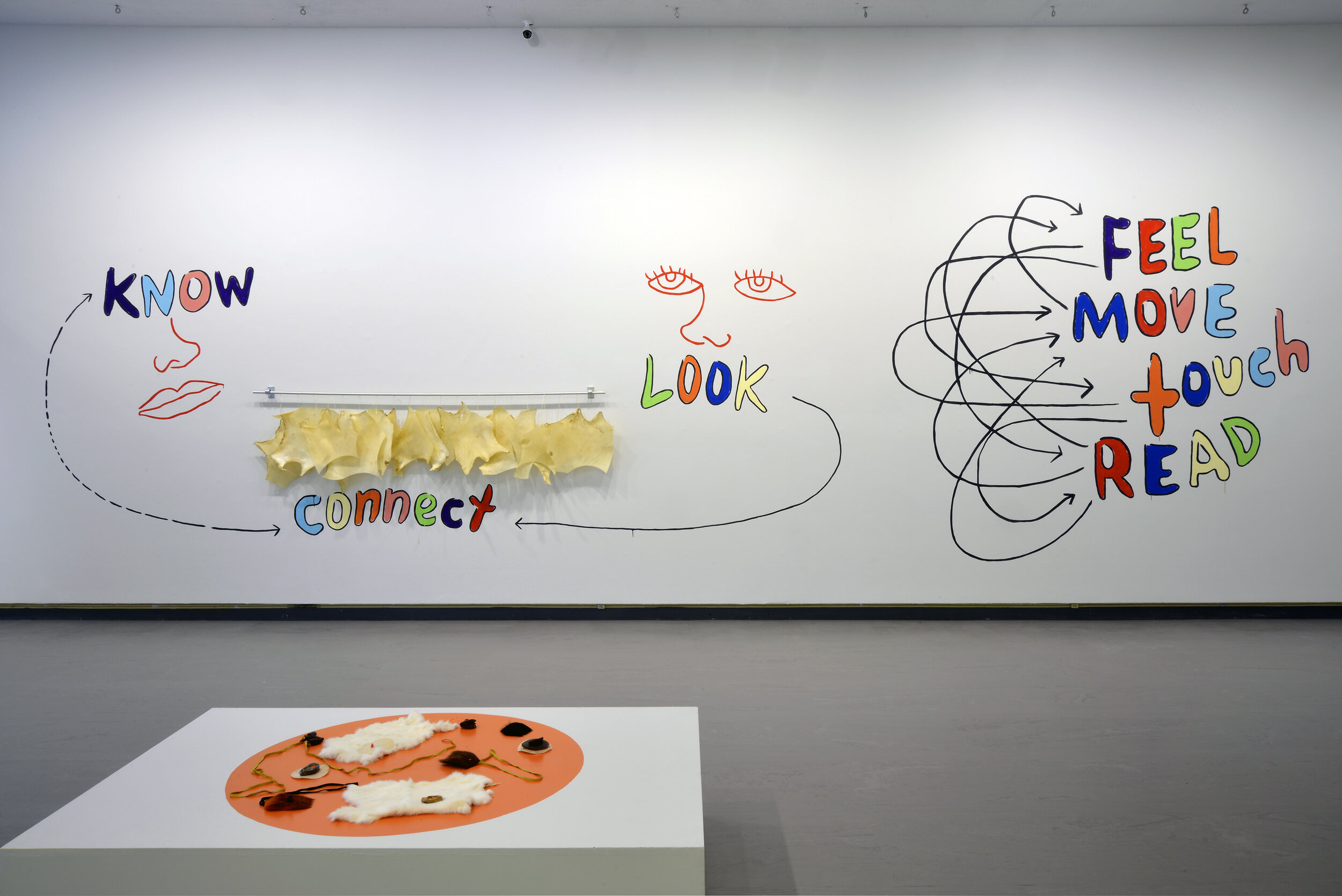

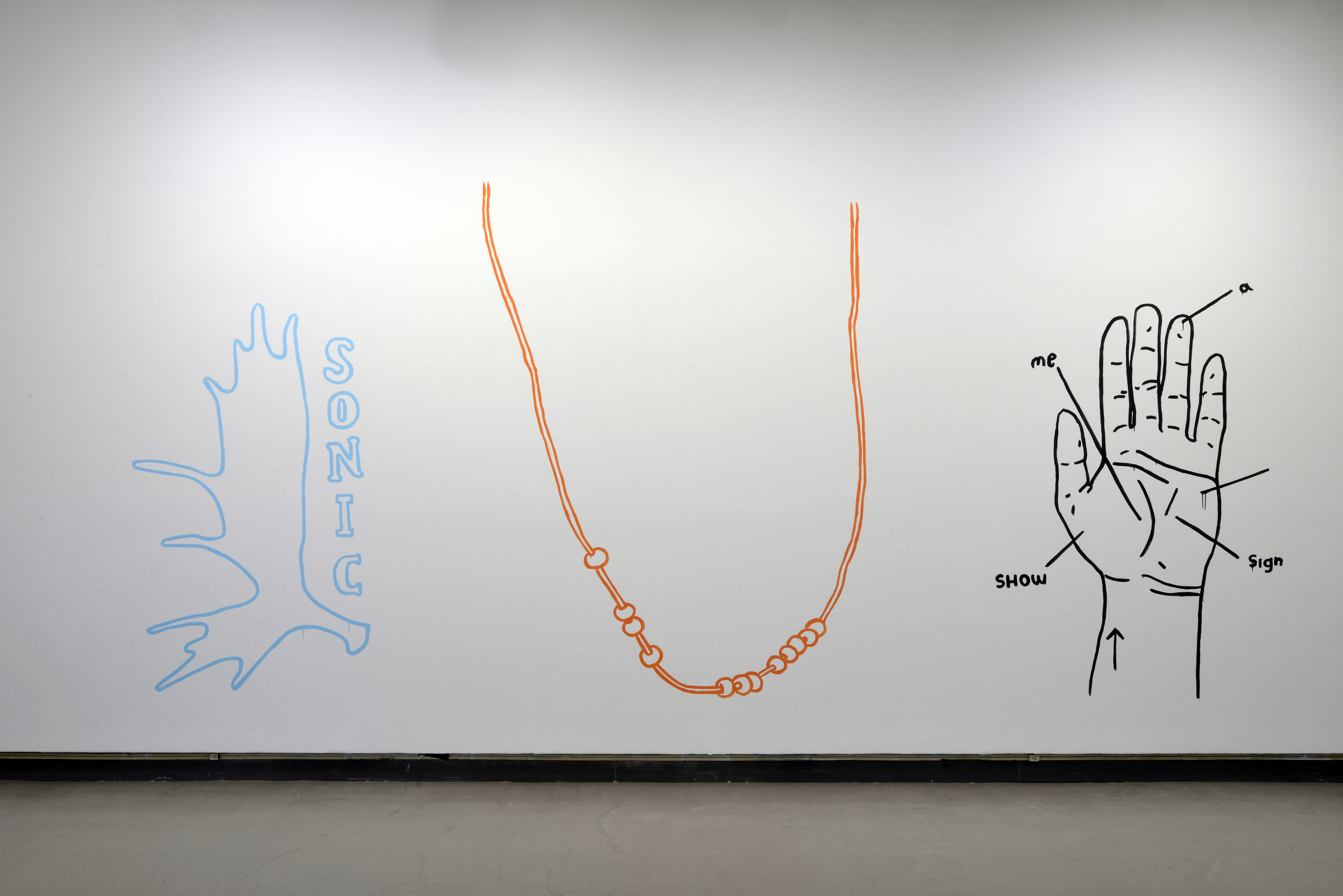

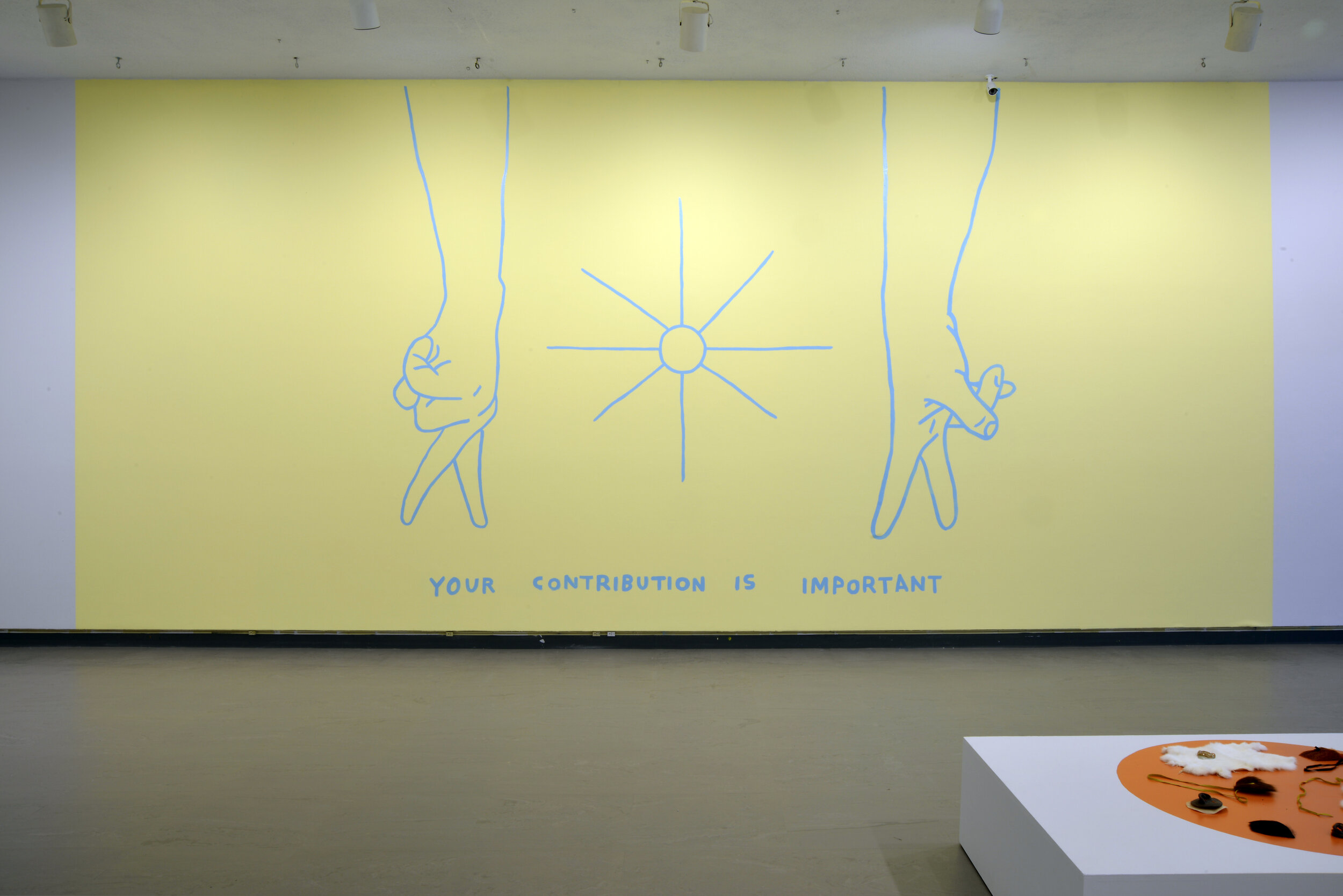

These drawings look to me like notes from a meeting I was not part of, but it feels familiar. Taking notes as drawings is something that I have always been drawn to; recently, I have practiced this kind of notation more regularly, embracing it. As a young student taking notes in class was one of the things I hated most because it was a distraction, and I could never "keep up." In contrast, it is common practice in Indigenous spaces to call for presence and attention by asking that people do not take notes. When I was young, I always felt vindicated in these moments, where the group was called to participate in a way that aligned with my skills and attributes. There is no one way to learn, to teach, to speak, or to perceive. We are all given special gifts. In these drawings, repeated references to speaking, hearing and seeing, bring our attention to those senses. The beadwork images, hands walking together, and the word "connect" and "Collectively" all reference community, gathering, or our aptitude to be together.

I want to let the reader into some more of your process. There are concentric circles of experience and understanding existing in this work, you held workshops, art-making studios and discussions with students at Winston Knoll's Deaf and Hard of Hearing program. Together you share the experience of what you all accomplished, felt, understood and made. Logan, you shared some more details of what that experience was with me. In this essay, I pass on some of what you told me but not all of it; and I am sure there were details from those experiences that remain between you and the students alone or just you. The strategy of not telling all, carefully choosing what aspects to keep private is practiced and powerful. Our Indigenous family and ancestors have used it to keep cultural knowledge safe from the consumptive prying hands of anthropologists and colonists. Within the disability movement, the slogan "Nothing about us without us" reminds everyone not to represent others. Not to "speak" for someone else's experience because we cannot know all or share all, and it is unethical to try or claim to do so.

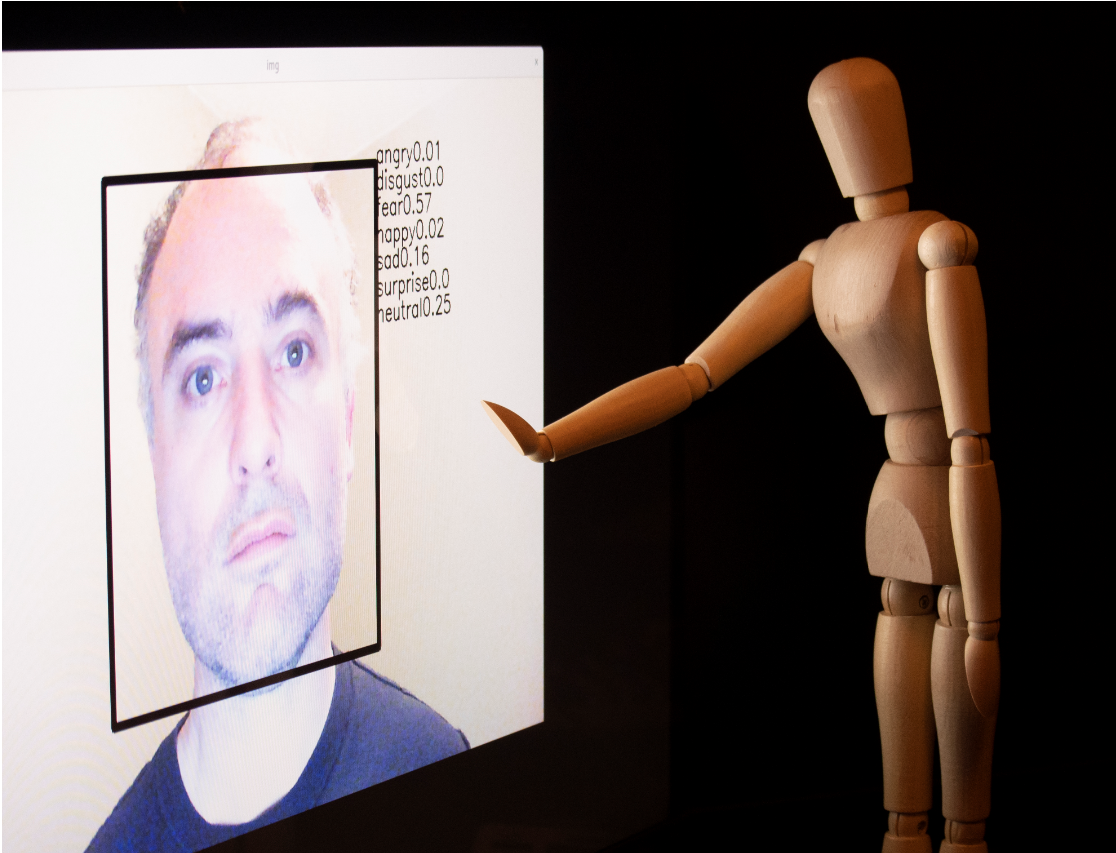

When you told me that primrose and tobacco, in a sense, speak in screeches that are inaudible to our human ears, I was thrilled and am not surprised. I recently listened to the Lenape creation story; one aspect that resonated with me was that kishalawowan made it so humans would have to use plants and animals to communicate with the spirit world. we cannot, or most of us do not have a direct connection. We use plants and animals to pass our messages on. There are so many forms of communication happening around us that we might not be aware of.

Anushiik waak Katwalill niijoos

Vanessa

Vanessa Dion Fletcher is a Lenape and Potawatomi neurodiverse artist. Her family is from Eelūnaapèewii Lahkèewiitt (displaced from Lenapehoking) and European settlers. She Employs porcupine quills, Wampum belts, and menstrual blood reveals the complexities of what defines a body physically and culturally. Reflecting on an indigenous and gendered body with a neurodiverse mind Dion Fletcher creates art using composite media, primarily working in performance, textiles, video.