Judy Anderson, As She Walked. Courtesy of the artist.

Coyote continuously whispers in Anderson's ear, "yes, you can joke about something while simultaneously being completely serious.” - Judy Anderson

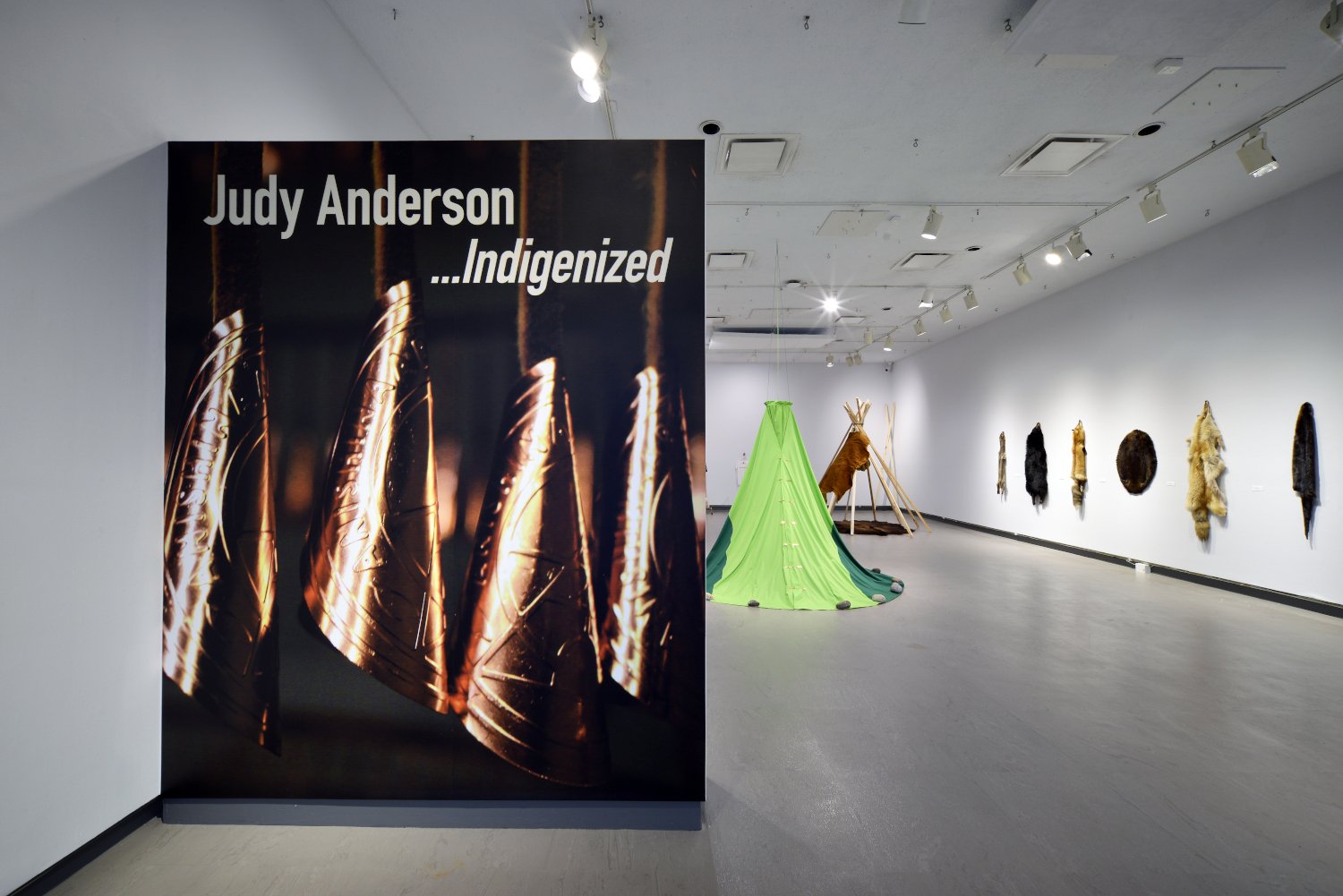

Through multimedia installations that stimulate the senses Judy Anderson interrogates what it means to “Indigenize” a place. After more than two decades of creating sly and meaningful interventions to mark her presence in the world, Anderson’s work unquestionably pronounces nêhiyaw as integral to this place, known as Treaty Four territory.

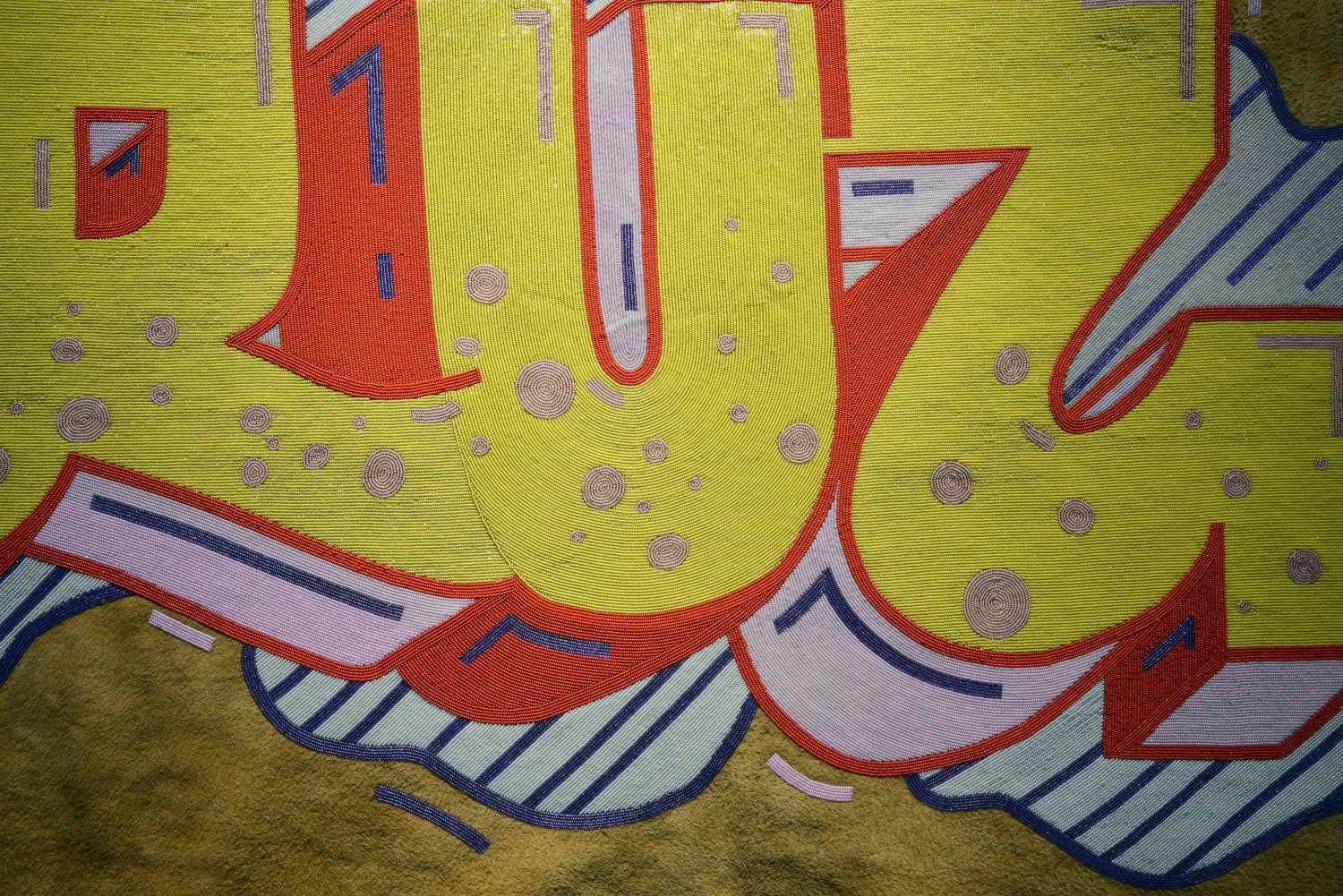

Judy Anderson is nêhiyaw from Gordon First Nation, SK. Anderson’s practice includes beadwork, installation, painting, three-dimensional pieces, and collaborative projects. Her work focuses on issues of spirituality, nêhiyaw intellectualizations of the world, relationality, graffiti, colonialism and decolonization. She is an Associate Professor of Canadian Indigenous Studio Art in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Calgary.

Artist ↑

Judy Anderson

Essay ↑

“A Career Indigenized: Judy Anderson’s … Indigenized Invites Us to Use All Our Senses to Engage with Indigenization and Decolonization”

by Brenda Macdougall

I fell in love with Judy Anderson’s art when we were at university together and I’ve watched with excitement her growth as a professional artist for the past twenty years. Now, as then, Judy doubts her extraordinary insight and capacity to advance the theories and methodologies tossed around in academic spaces. Her work is a physical expression of ideas, concepts, and perspectives that others attempt to articulate in writing. She provides us with an opportunity to think about decolonization and Indigenization through beads, sculpting, performance, and installation. In short, she does with art what the rest of us attempt to capture with terms like relationality and radical resurgence.

My life has been immeasurably shaped by Judy’s art and I count myself incredibly lucky to have a few Anderson originals hanging on my walls. Being friends with an artist means that you get to participate in some small way with the production of their creative practice—to discuss it as it’s being made, be asked to provide feedback on what’s being conceived, and then be present at an opening and view the final pieces hanging in a gallery. Occasionally, like now, you even get to participate in a solo exhibition by writing a short essay about the work.

Steeped in wit, irony, emotional intelligence, and just a hint of sarcasm, Anderson’s, …Indigenized represents the culmination of a lifetime of thinking about how Indigeneity is reflected in mainstream Canadian society, unmoored from vital questions of how to dismantle colonial systems of oppression. Her work, therefore, reaches different audiences in distinctive ways. She encourages Indigenous peoples to consider how to free themselves from oppression by exploring the beauty of their cultures, while at the same time she challenges non-Indigenous peoples to reflect on the power and privilege they gained as a result of colonial systems before they engage with us as allies in the act of Indigenizing. The different pieces here motivate and demand that we challenge ourselves to critique our social location and positions, to consider acts of Indigenization and decolonization more critically.

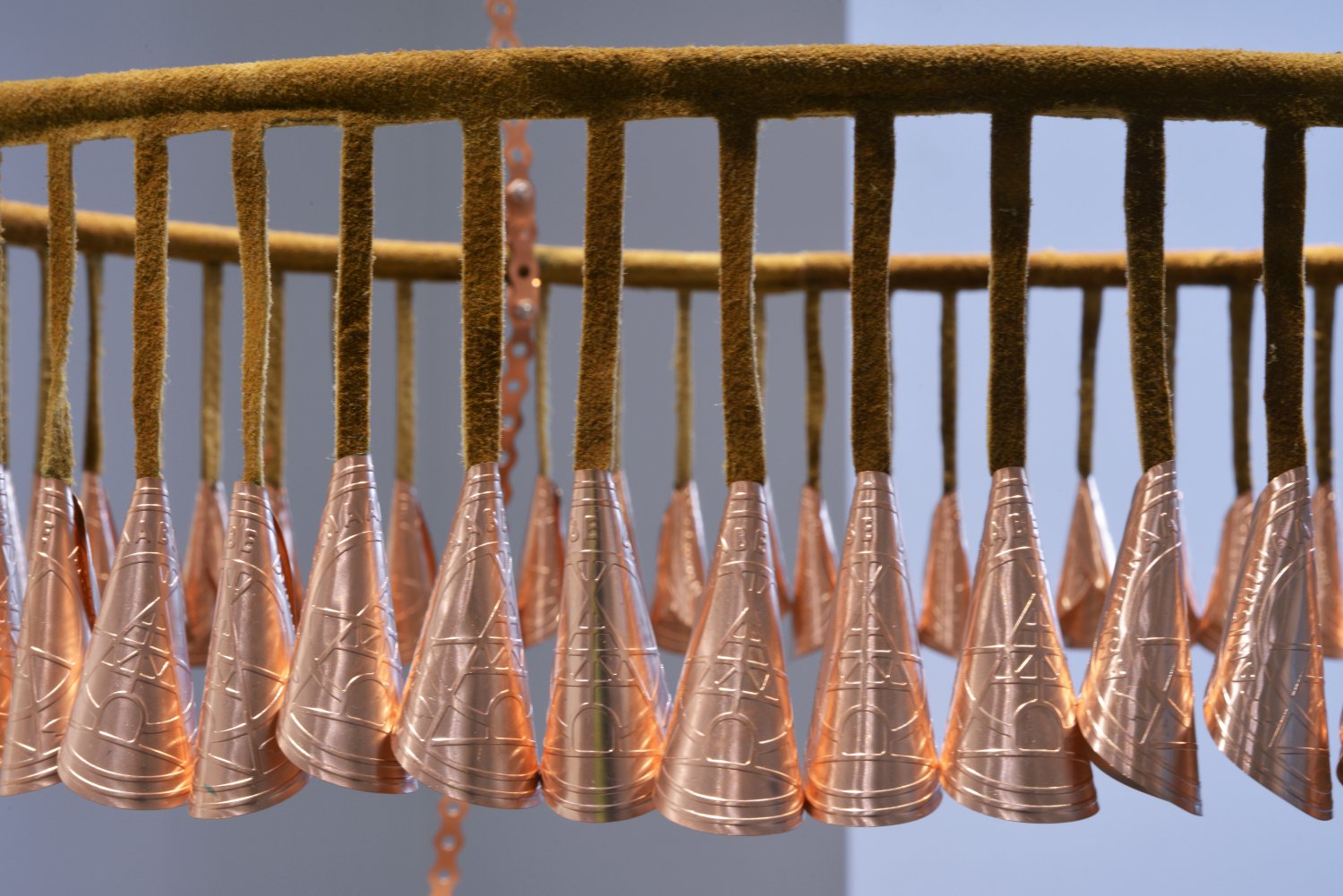

Inspired by the sound of a jingle dress in a university hallway, Judy created “As she walked down the hallway, she unintentionally … Indigenized.” To non-Indigenous people, the aperture frame may appear to be a chandelier, a cake, or even the shape of a woman in a dress, but the abstract shape represents the thunderbird. Often represented in art as two triangles point to point, the thunderbird is a powerful spirit being that protects humans but, as part of our religious tradition, was scorned and undermined by colonial impositions of Western thought. Its return, in this exhibition, in abstract form is an important step towards making us whole again. Made of copper, a metal native to North America and traded amongst Indigenous nations pre-contact and post-contact, the sculpture is constructed from materials that speaks directly to Indigenous peoples. The sensory aspects of the sculpture are created by the sound of a jingle dress and smell of smoked hide. It invites us to feel, to emotionally connect ourselves, to the symbiotic—but tension-filled—relationship between Indigenization and decolonization.

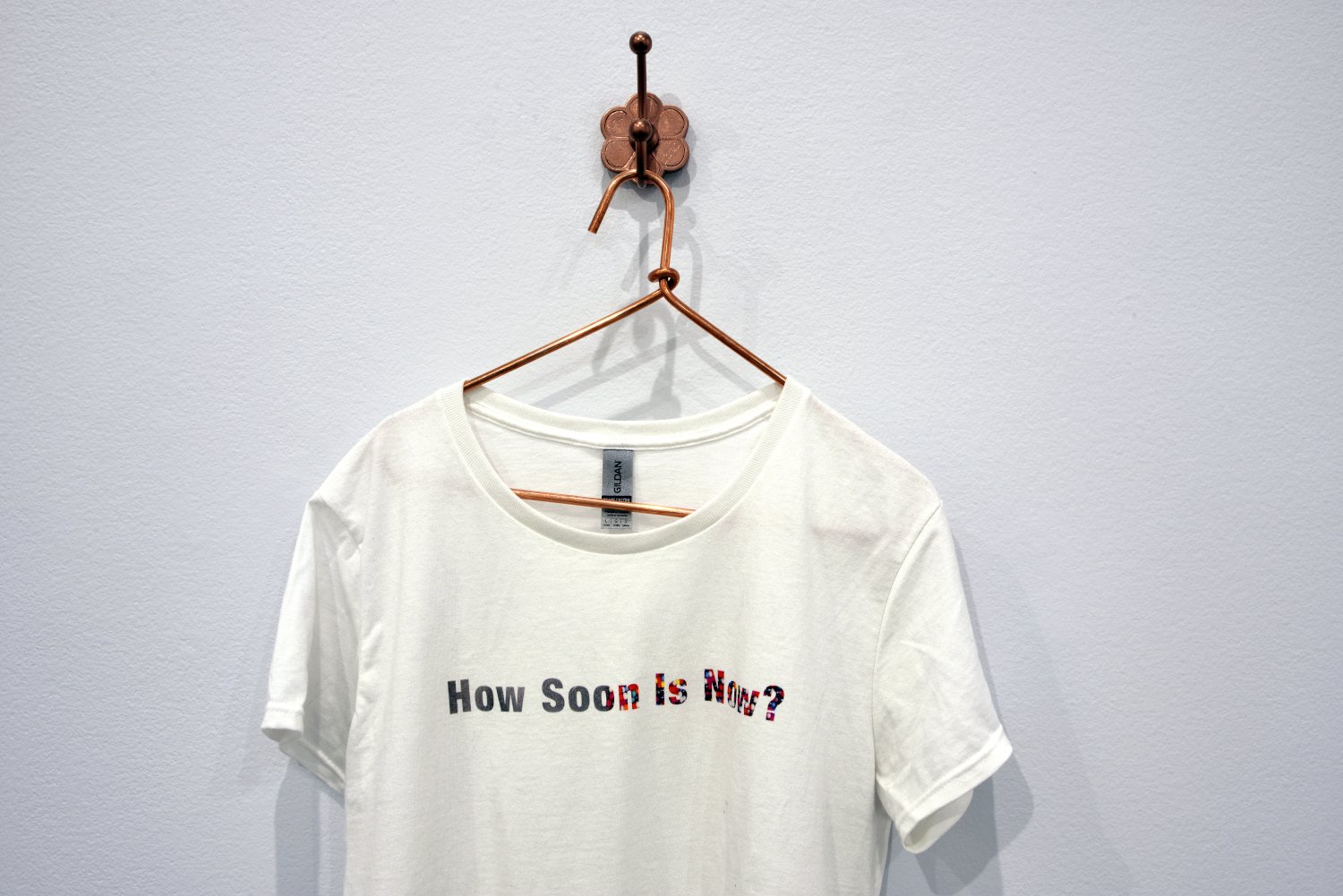

Importantly, Judy’s art asks non-Indigenous people to think about and reflect on their privilege, on the racist and stereotypical tropes they might yet possess about Indigenous people, or to consider how to contribute to make space for Indigenization by doing the labour of decolonization. “It really is a circle…” finds inspiration in her deliberate choices to wear t-shirts as an artistic intervention. For years, Judy has worn t-shirts with provocative imagery and has waited expectantly for someone to ask her about them—nobody ever has. So, this work of t-shirts hung on a copper clothes rack is another invitation to engage with imagery and to reflect, discuss, or comment on what they mean when worn by Native people or, conversely, when worn by non-Indigenous people. Pointedly, the t-shirt she made specifically for this installation comes with the statement, “what are you willing to allow.” This is, deliberately, not presented as a question. Once again, the use of copper and the smell and texture of the fur on the shoe frame below the t-shirts, are reminders that Indigenous materials are authentic and present in our world. This work, and indeed the entire exhibition, envelopes Indigenous people in spiritual traditions but is reflective of a biting wit and sense of humour. Her decisions allow us to feel the effects of colonial trauma authentically, invite us into ceremony and language through material choices, and tease us gently but persistently to interrogate our knowledge and beliefs.

…Indigenized is the culmination of a life’s work, but it’s also a promise of what is to come. In the first instance, it brings together all the elements integral to Judy Anderson’s art practice: honouring relationships (including to self), exploration and expression of spiritual traditions, and an invitation to confront and dismantle colonial systems. We can see, hear, feel, and smell the beauty of her work through the mediums chosen—jingle cones, smoked hides, soft furs and hard beads in three-dimensional physical and sound installations. …Indigenized is a raw and reflective experience that allows all visitors to actively engage with Anderson’s exploration of spirituality and belonging. Through the prompting of laughter, viewers open their hearts, minds, and sensations to the messages Judy embeds in her work. Through her art—physical and performative—and sartorial choices in clothing and jewelry, like those worn in her headshot, she invites, and importantly welcomes, response. Similarly, this exhibition is a way to reflect on whether and/or how viewers will comment, ask questions, or become engaged in the ideas presented. These subversive choices have been a part of her practice well before she was a practicing artist, and over time she’s refined her thinking as much as she’s honed her artistic talents.

Besides being Judy’s BFF, Brenda Macdougall is the University Research Chair in Metis Family and Community Traditions and also works with the Provost’s Office on Indigenous Engagement strategies at the University of Ottawa.

Installation Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall