Essay ↑

the excess is ritual

by Noor Bhangu

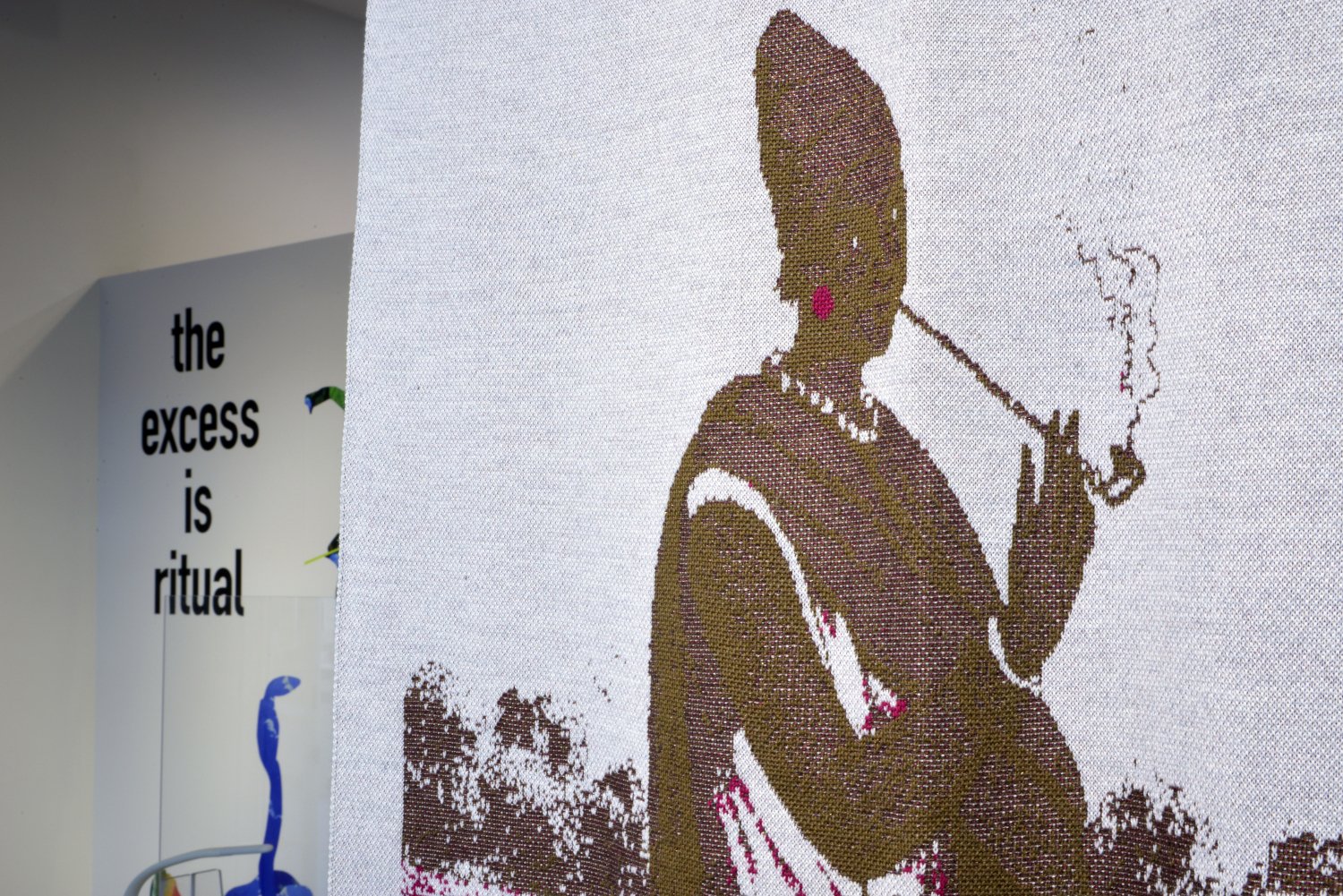

The language used to name the workings of this exhibition was first introduced by Joseph Massad in his 2007 text, Desiring Arabs, to analyze the emergent homophobia of post-Independence Egyptian literature. While our exhibitionary endeavour is more global and transcultural in its reach, the exhibition title retains from its conceptual ancestor an ethic of queer historiography, which can only be understood as the deep desire of queers to place themselves in the wound of history. Anchored around diverse representations of queer life, the excess is ritual cradles the excesses and rituals of history to initiate a present and future coming of all that is lost and all that remains to be recovered.

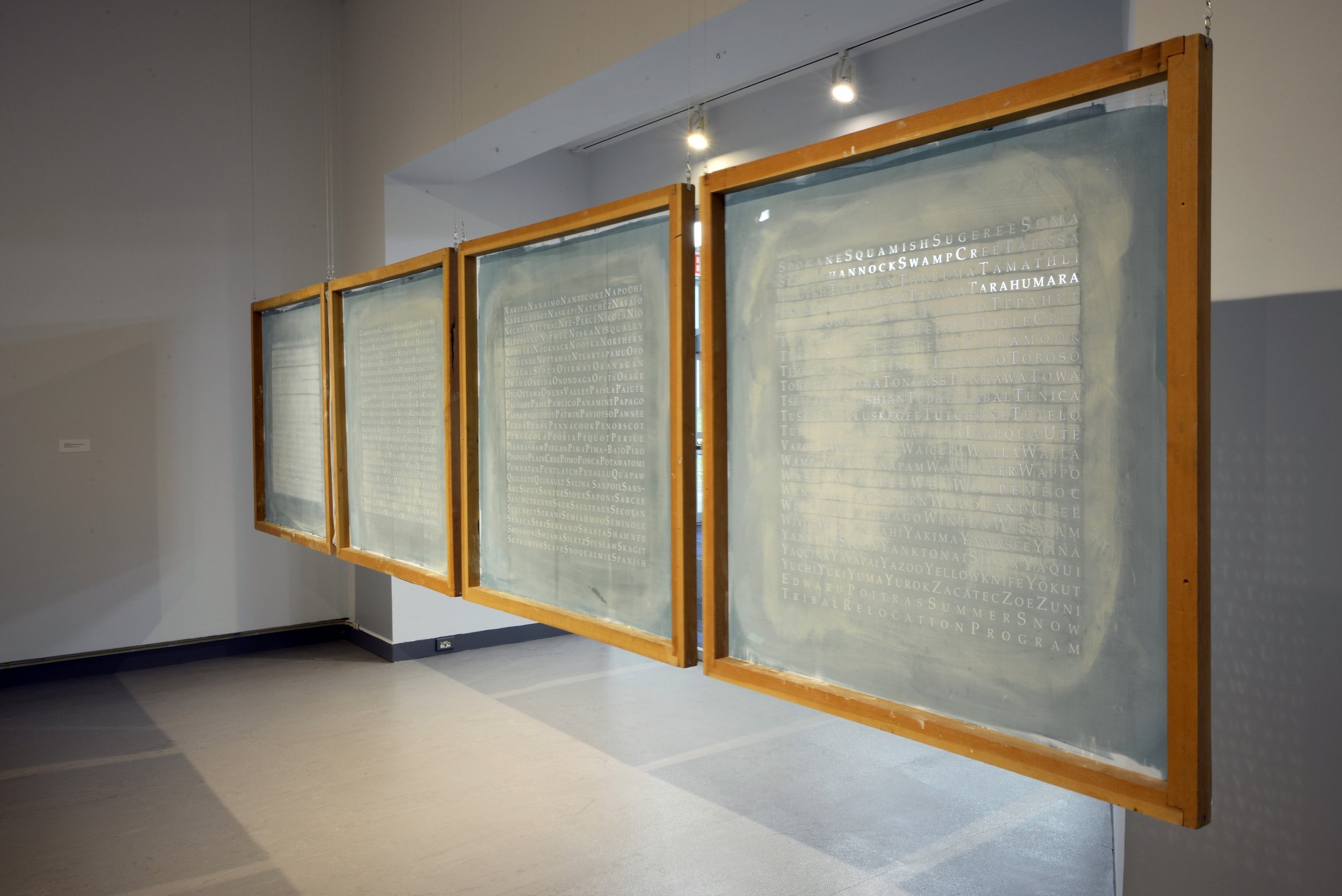

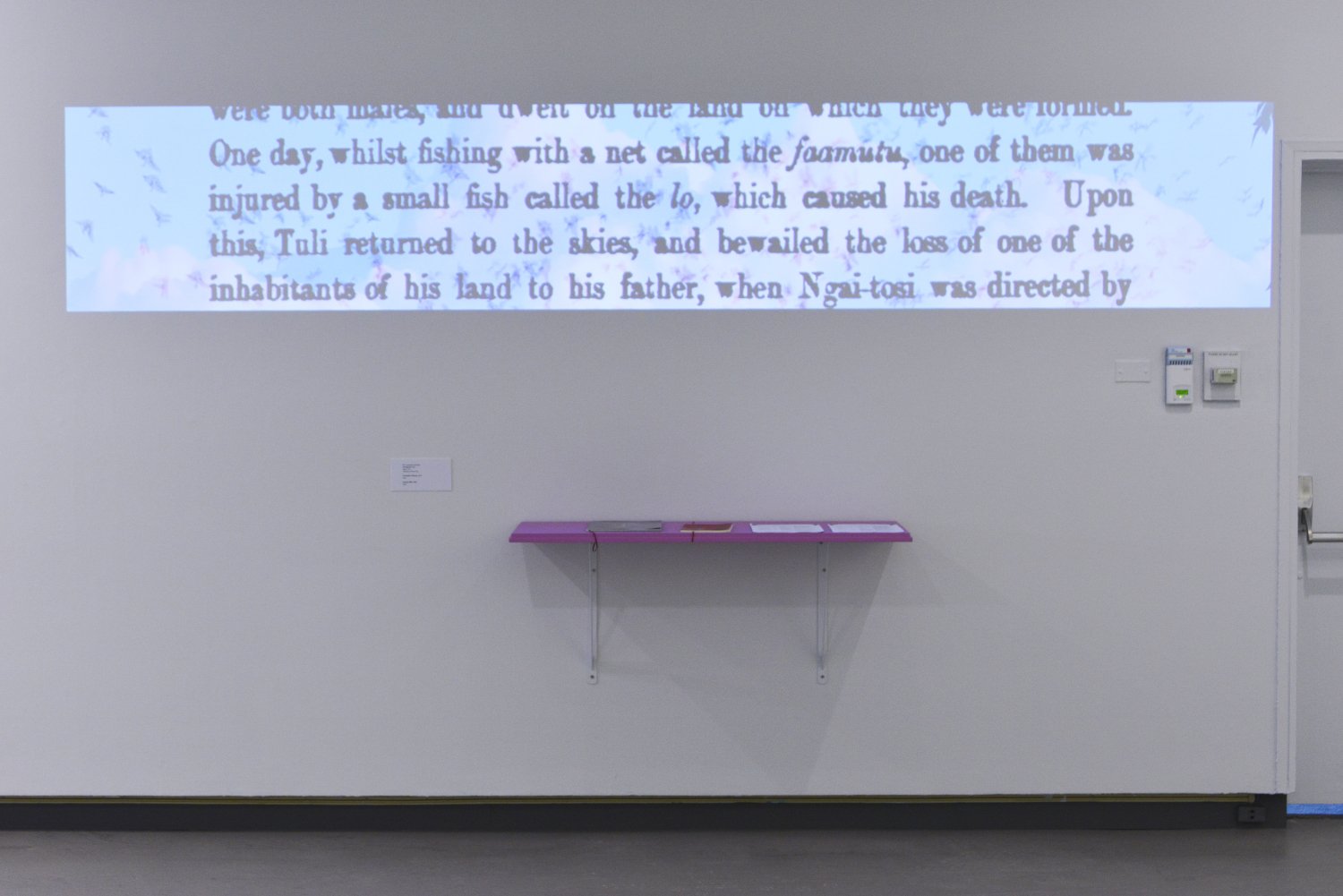

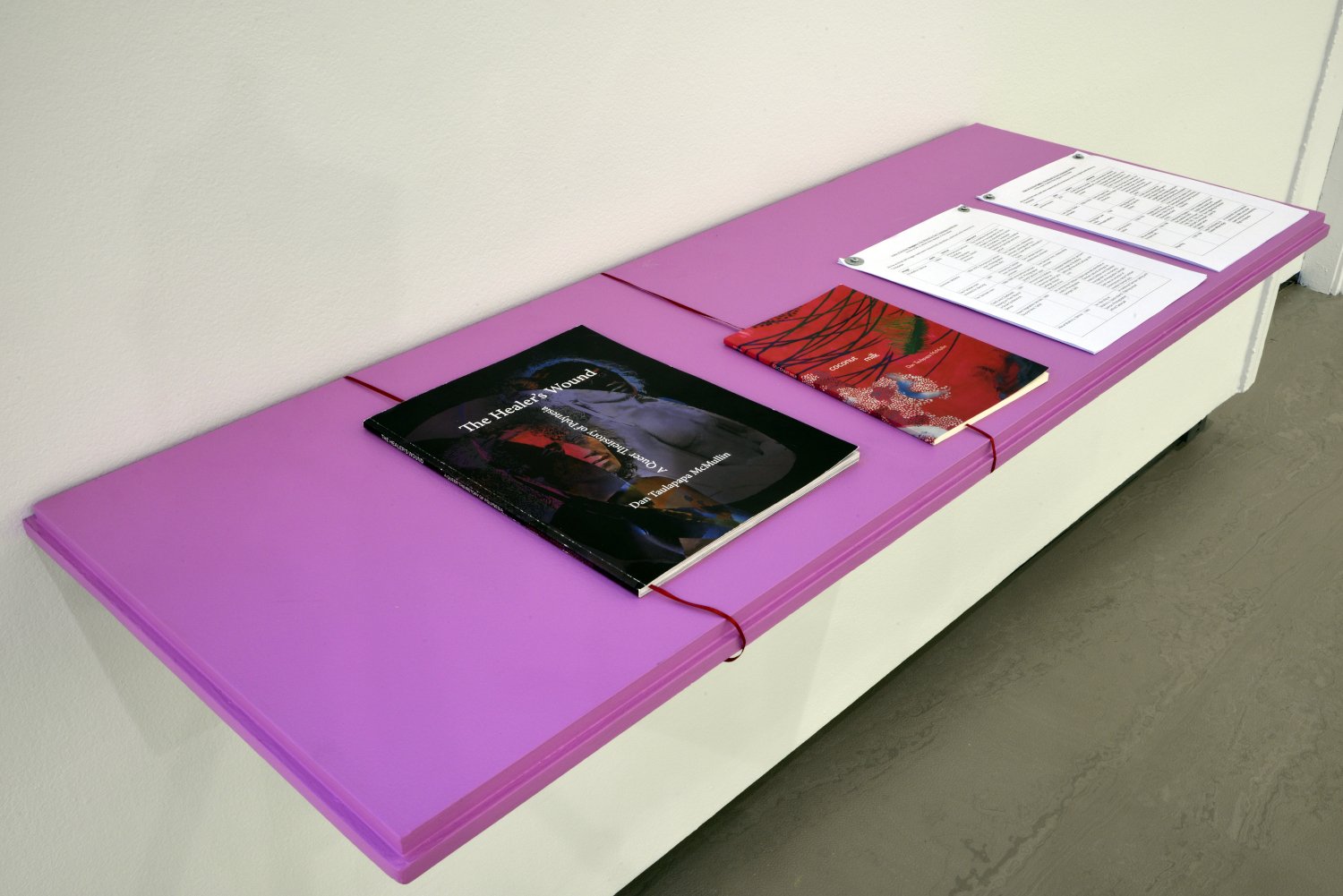

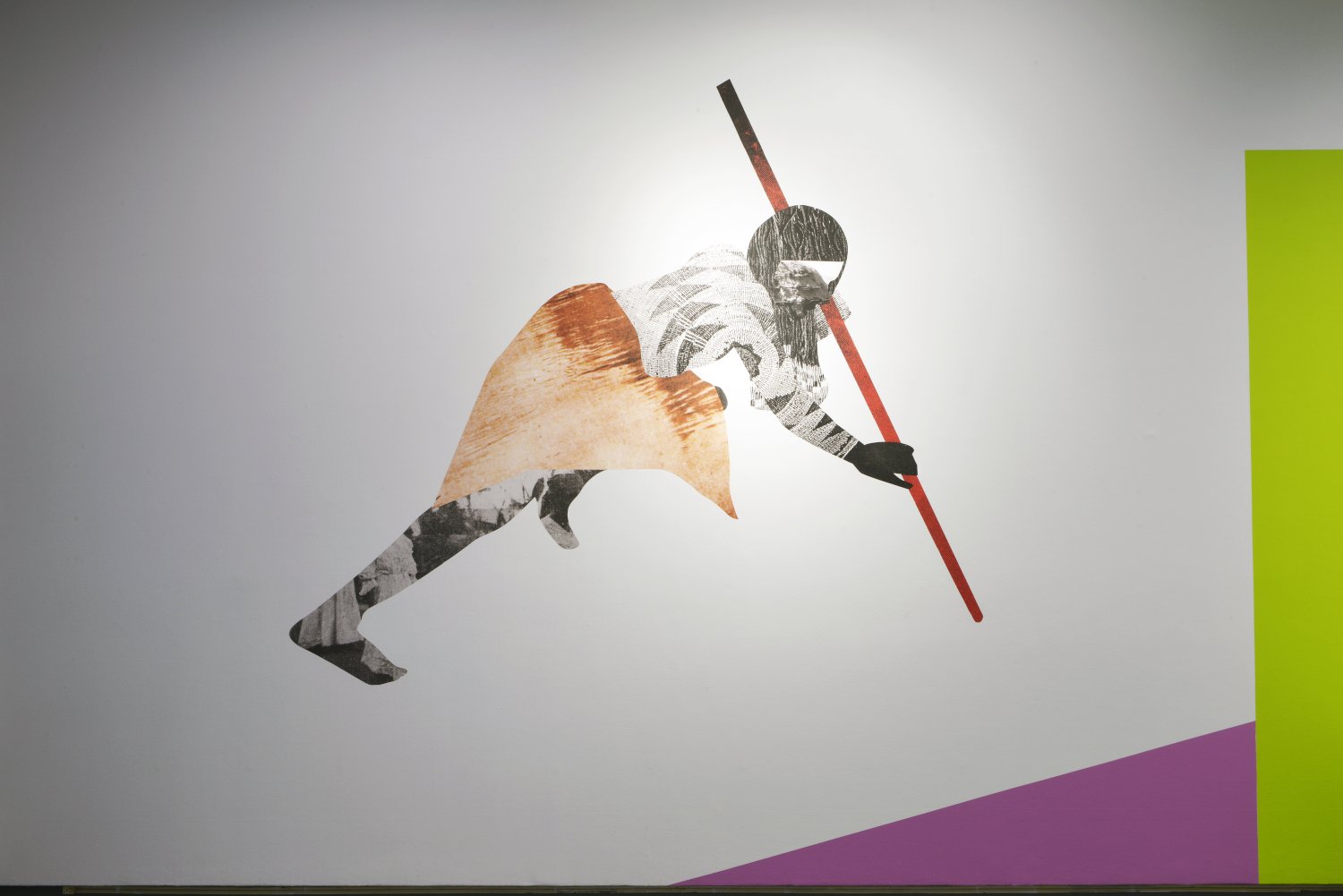

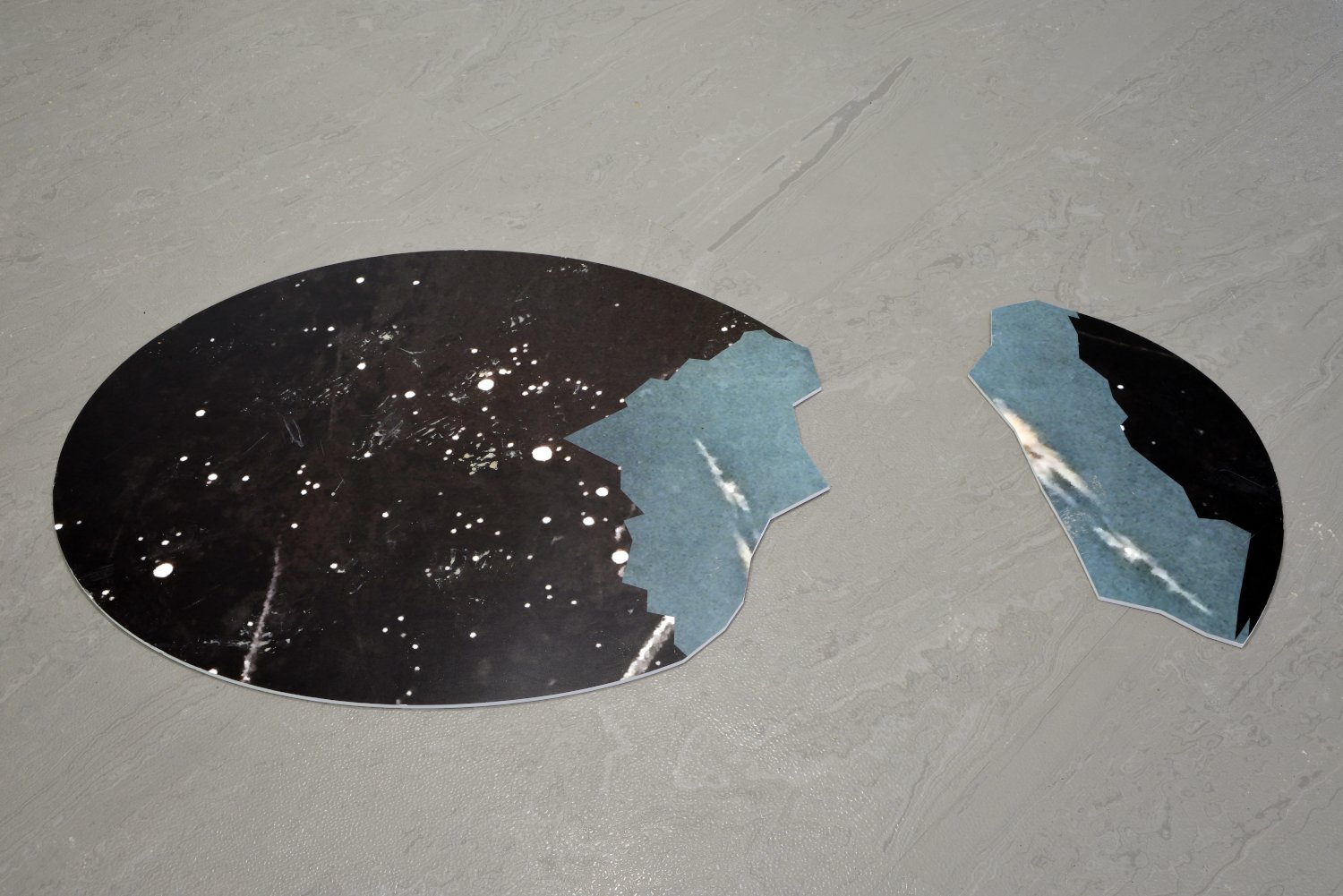

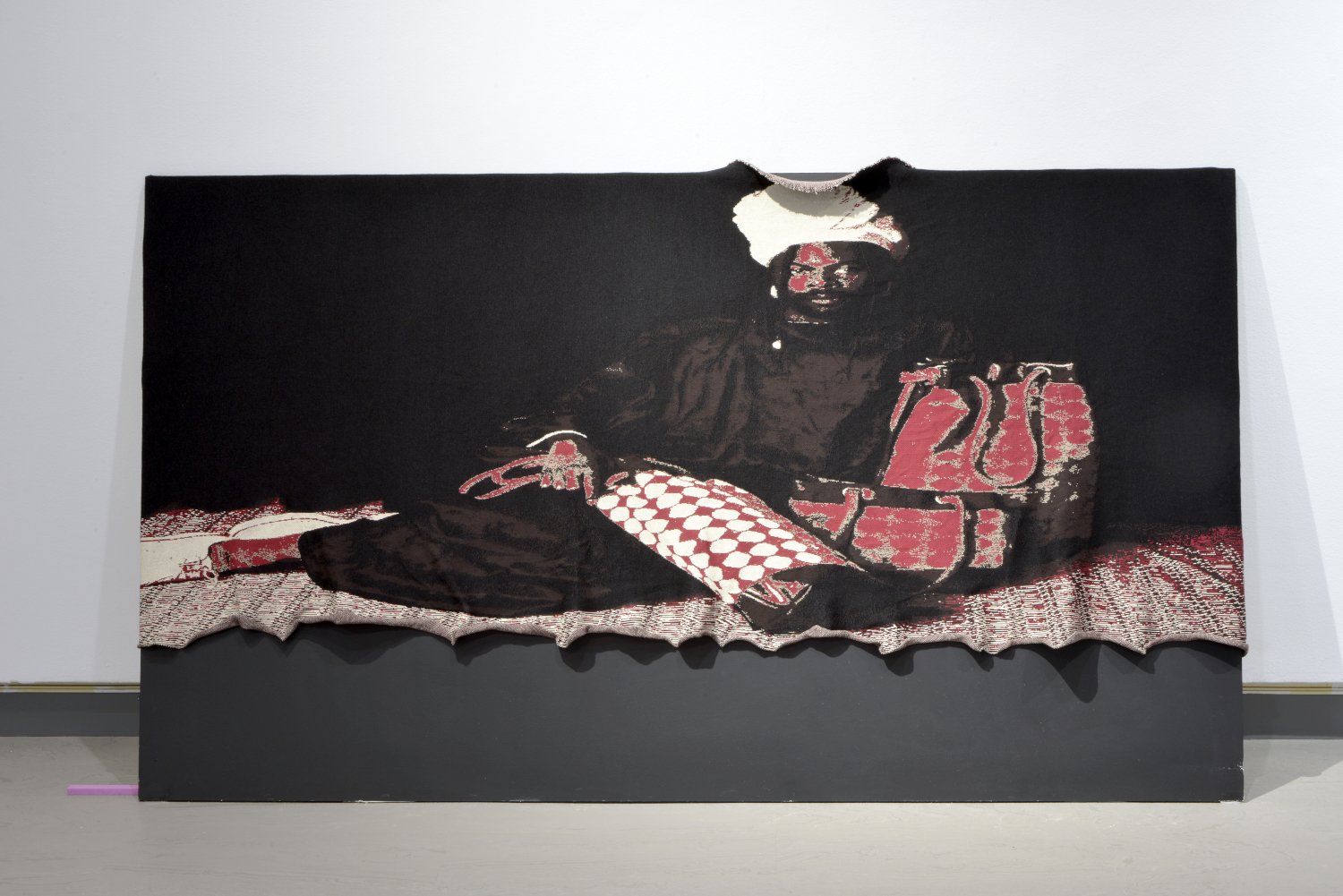

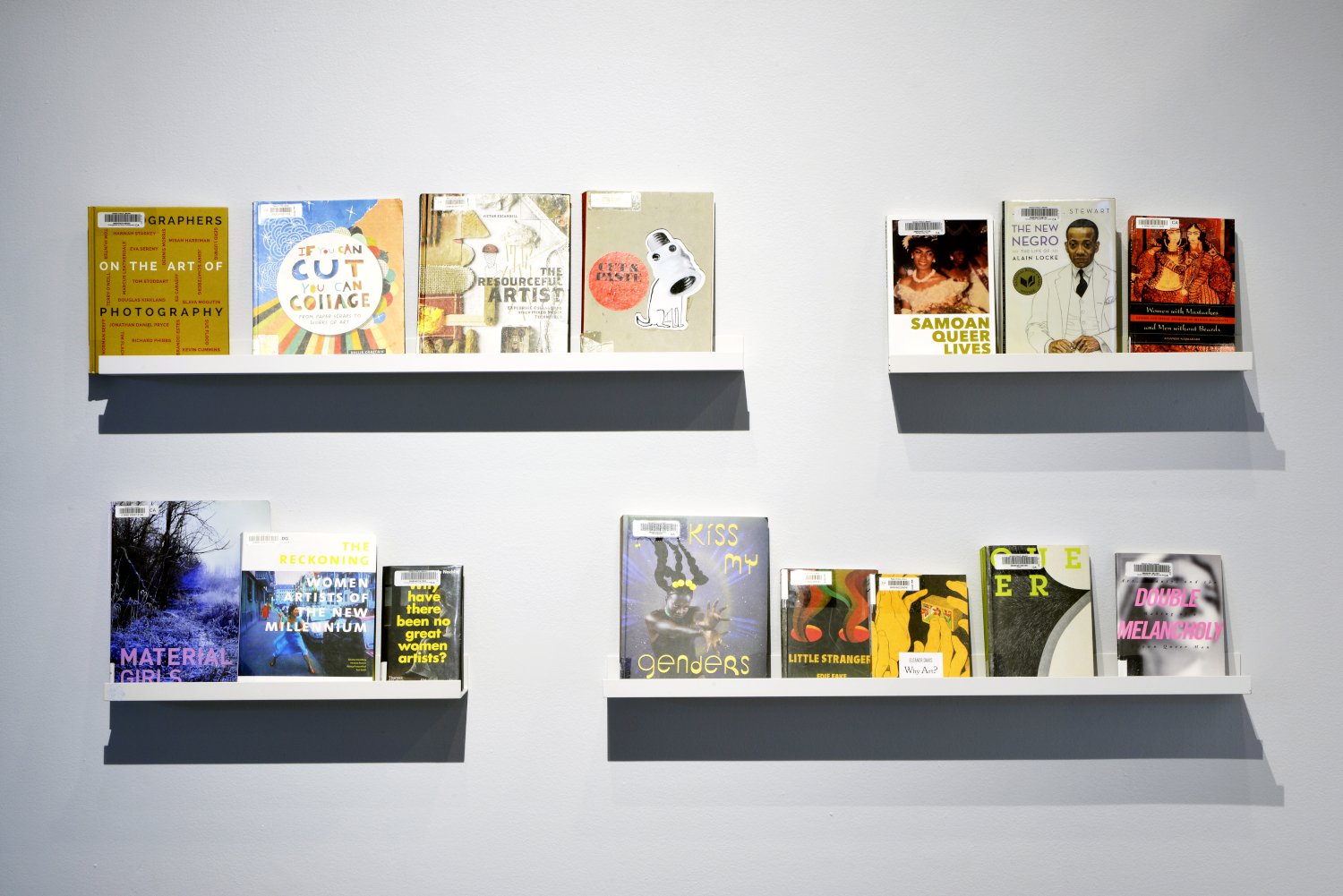

Consistent with exhibition’s troubling history and historiography, the excess is ritual beats an archival impulse, which is defined by Hal Foster, as the desire “to connect what cannot be connected.” In the work of Anna Binta Diallo and Dan Taulapapa McMullin, the highly subjective technology of collage is used to form new bodies of knowledge from colonial and, often, disparate sources. Anna Binta Diallo’s Ritual series includes three figures performing the rituals of celebration, menstruation, and hunting, their bodies filled in by scraps from old magazines, almanacs, and other printed matter. Dan Taulapapa McMullin’s two books, Coconut Milk and The Healer’s Wound, are compilations of the artist’s research into Samoan queer their stories, with specific attention paid to the recovery of Fa'afafine identities. The Wound, a new video work, expands on this research by collapsing visual and textual references to queer practices and identities recorded in colonial archives. The figures produced by Diallo present critical appropriation as part of a larger dialogue about decolonization of archives, while McMullin’s work travels across familiar colonial tropes to forge an eventual return to its source.

Grounding the past and future archives is an installation by artist Sahar Jamili. Disturbed by the monstrous turn in the depiction of brown bodies in Scandinavia and the Euro-American world, Jamili appropriates the monster to build an alternative rhetoric of anti-racism. In their installation, Monster, me, more, strange creatures take up residence above a wrinkled bed in a child’s bedroom. Instead of disturbing the scene, the monsters borne of Jamili’s hands are casually domesticated to subvert their internal ideologies. The monstrous excess in the case of Jamili’s installation is ritualized to think through the social politics of contemporary time and the location of brown queers within.

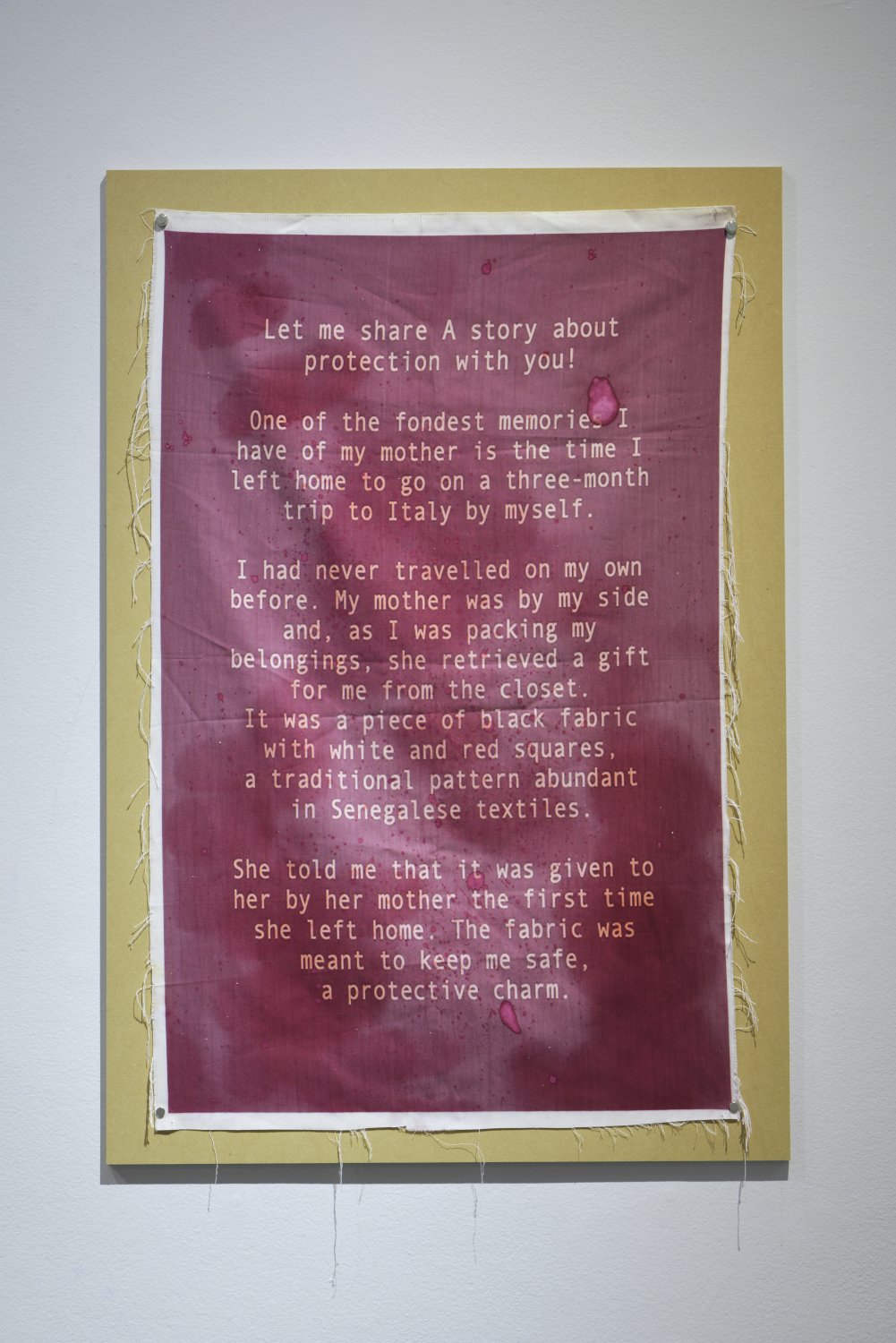

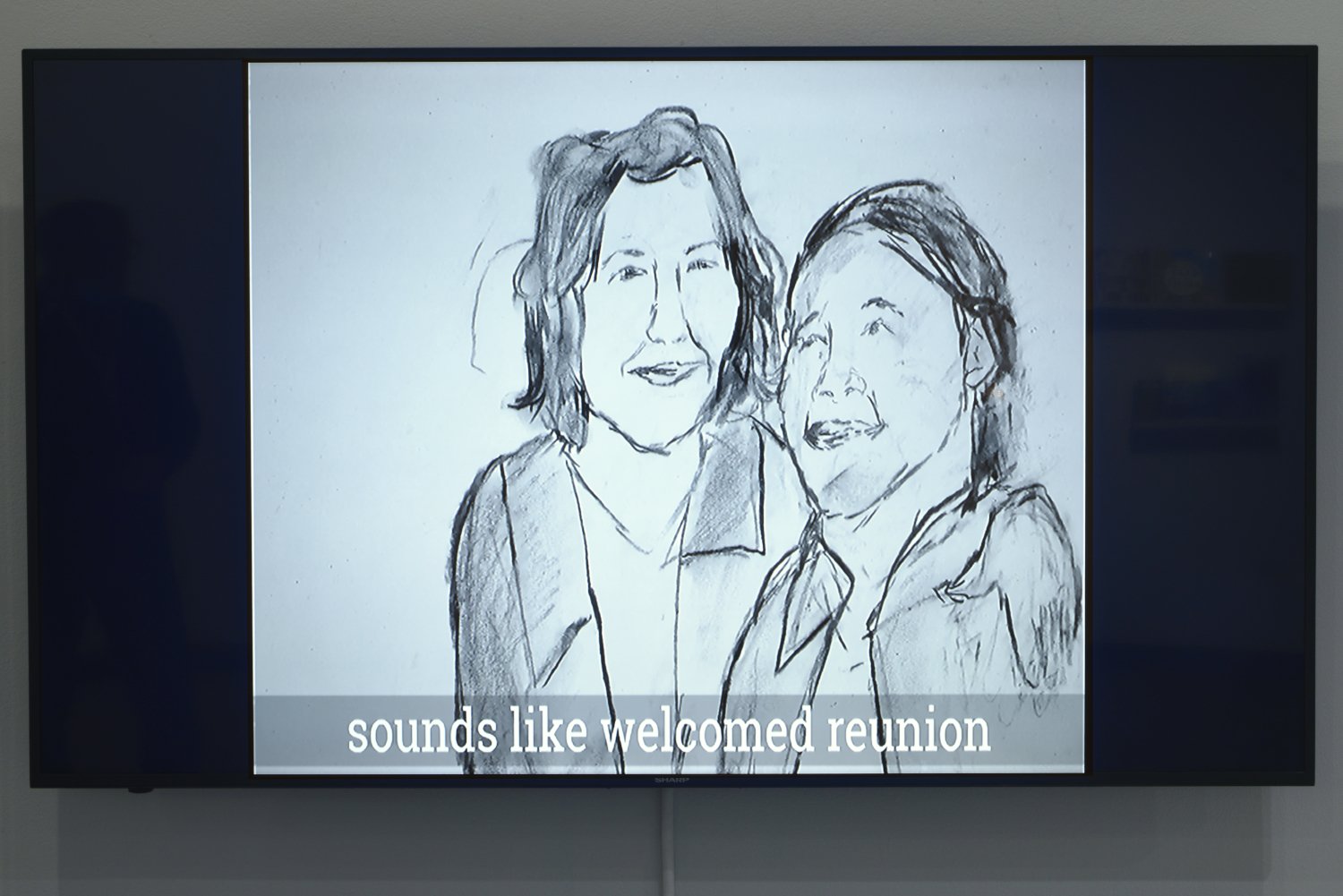

By contrast, the work of Damien Ajavon, Darcie Bernhardt, and Carmel Farahbakhsh moves away from the density of archives and onto the imaginary plane of critical fabulation. In the work of Saidiya Hartman, critical fabulation can become a way of working with scatted references to produce historical facts. Ajavon’s Dyptique de l'imaginaire visualizes a conversation between the artist and their ancestor, separated across borders as well as colonial and post-colonial time. The artwork memorializes in thread a feminist and queer genealogy, whose transference was broken in time, but one which can easily be recovered. Bernhardt and Farahbakhsh’s work similarly explores the fruitful conceit of relation. Nanuk and Bibi is a short video, which includes hand-drawn representations of the artists’ grandmothers, as they sip tea, gossip, and sit in the pleasure of birthing future queer generations. While Ajavon’s work stretched an intimate line between blood relations, Nanuk and Bibi fabulates relation across cultures. The imagined relation becomes a new memory for the artists, even though the ancestors did not encounter each other in their mortal lives or even understand the queerness of their future kin. The works of Ajavon, Bernhardt, and Farahbakhsh exists in excess of historical knowledge and has the potential to shift what we know as historical truth.

But of course, the present representation and future inheritence of queer history too has its limits. As Walter Benjamin writes, “The true picture of the past flits by [and] the past can be seized only an as image which flashes up at an instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.” In bringing together aesthetics of queer life, queer history, and cross-cultural relation, this exhibition lingers at the ritual passage of time, captured in asymmetrical visuality, to seize on encounters with an earlier, current, and future queer life.

While these moments of recognition are bound to disappear, as prophesized by Benjamin, it is my hope that our ritual desire to recover persists.