Lasha Mowchun, you and me and me and you, 2014, video, 7:14, colour. Photo courtesy of the artist.

On the Record ↑

by Blair Fornwald and Gary Varro, co-curators

Curators’ note: The exhibition Off-Centre: Queer Contemporary Art in the Prairies has largely evolved from a recurring conversation that we have been having for years, about what it means to be queer artists and cultural workers in Regina, a small Canadian Prairie city. What follows is a version of that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

G: So let’s start with the title. What do we mean by “Off-Centre”?

B: “Off-Centre” speaks to the destabilizing goals of the exhibition – both in terms of gender and sexuality, and in terms of regionalism. Geographically, we’re in the centre of the country but culturally and politically, we’re peripheral.

G: We did talk a lot about titles, and a lot of them seemed so silly and done-before, Homo on the Range, that sort of thing. Off-Centre speaks to privileging a different point of view. And an intentionality – we’re off-centre because we want to be.

B: It speaks, perhaps to the politics of staying where you are, or choosing to live in a peripheral region despite, or perhaps because, it’s difficult.

G: And yet in your experience as a curator, you said that regionalist shows weren’t really your thing. Why is that?

B: Well, I was questioning why “the Prairies” had to be the focus. Often, regional shows can be kind of dull, bringing work together somewhat arbitrarily and putting them under the banner of “celebrating the talent in the region.” But this exhibition aims to unsettle some popular narratives – both about the region and about queer lived experience – that the Prairies are homogenously conservative and straight, that we somehow live outside of contemporary discourse, that queer folks can and must leave, that leaving is always a matter of choice. There are all kinds of reasons people live where they live. I’m wondering if you could speak to that.

G: When you approached me about being involved, I agreed, because we’ve talked a lot about staying here, as artists, curators and cultural workers. And “Why do you stay here?” is often the first question that comes up when we talk about being queer on the Prairies, because it’s often thought of as a place that’s very heteronormative and conservative, that doesn’t have a lot to offer in the way of progressive ideas and attitudes. In fact, it’s often quite challenging and unpleasant to be a queer person living on the Prairies. And yet, there’s a happy and flourishing queer community here, and it’s growing. Queen City Pride has grown in leaps and bounds here in the last ten years. And lot of that, I think, has to do with the corporatization of queerness in the bigger world. But the same critiques about what is and isn’t okay in the queer community – about intersectionality, police presence in Pride parades, the politics of inviting a straight ally to marshal the parade – are happening in Regina as well as in larger centres, and near-simultaneously.

B: I think a lot of it has to do with increased access to ideas proliferated on the internet and through social media? And that the notion of regionalism was stronger in the past. In the pre-social media landscape, conversations that were happening elsewhere around the world or on other sides of the country weren’t necessarily happening here.

G: We’re aware of those dialogues in a way that we weren’t before. The newspapers weren’t reporting subcultural stuff. You didn’t know those things were happening unless you knew somebody who lived there and you had a conversation with them on some fucking dial phone.

B: The world is getting ostensibly smaller because we’re having these dialogues simultaneously.

G: It’d be nice to debunk the notion that there’s something distinct about the people and the art of a specific place. It’s a bit of an untruth. In the case of Off-Centre, we make the case that there’s something unique about living collectively queer on the Prairies to amplify individual voices and expressions, which may be a goal of greater importance. The desire to create unique and meaningful connections to place is what Stuart Marshall would call a “necessary fiction – accepting what is known to be untrue in order to facilitate action.”[i]

B: “The Prairies” are themselves kind of a necessary fiction.

G: Yes. We’re already setting up a framework that is colonialist.

B: And yet, I think specifically for a lot of Indigenous artists, there’s a strong sense of land and place that resonates in their work. There are a lot of contradictions in this exhibition, where the work intentionally undermines the premises either set up or implied by a regional survey. And every artist in this exhibition participates in a broader contemporary art world. And all of them grapple with ideas that aren’t unique to this region. There are a few pieces, like Harley Morman’s Hankies or Kablusiak’s Atiga Agnak in the Style of George Jones, that we could certainly curate in a way that over-inscribes their regional specificity. We could read them as more “country and western.” It wouldn’t necessarily be responsible, but we could do it.

G: Maybe our regional exhibition paradoxically suggests that regionalism is a conceptual container that doesn’t hold a lot of water. I don’t even know if regionalism exists anymore.

B: On one hand, I agree. Conversations happening elsewhere are happening here too, but on the other hand, the Prairies are a more conservative place. Queer voices are perhaps quieter here. Taking up space, creating queer space, amplifying queer voices – are radical acts perhaps more necessary in communities like ours. So what keeps you here, Gary?

G: A bunch of things have kept me over the years. I moved away as soon as I could at 18 only to return 10 years later with no intention of staying. I moved back after traveling to Mexico for an extended period and spent all my funds, forcing me to live with my mom and dad until I could get back on my feet. I was going to give it two years before returning to the “real world.” That never happened. Then I fell in love, made a nest for me and my boyfriend, found employment at the MacKenzie Art Gallery as a preparator and at the Dunlop as a curatorial assistant. I started Queer City Cinema while simultaneously working in the film industry as an art director and production designer and pursuing my art practice. I had settled in quite nicely and became a total local. Years later I did relocate to Toronto but returned to take care of my mom after my dad passed. And I had just renovated my house in Regina, so I had lots of reasons to stay. Recently, it’s been more family obligations, a house that I know I couldn’t afford elsewhere, access to funding for both Queer City Cinema and my own art practice, and of course my job that keeps me here. I’ve been doing QCC for 23 years. It’s my baby! Regina’s a conservative place, and I want to make sure that there’s an alternative, scratchy, fun, transgressive, subversive element here that people would be surprised to find. But there’s also sort of a quirky, interesting, peculiar vibe that exists here, and that attracts me. It informs me, gives me energy, makes me feel like there’s purpose here. Why do you stay here?

B: Lots of practical reasons! I moved back here after grad school because I was broke. This is an affordable city, and the place where I had the most job connections. And then I established an artist collective here and got this job at the Dunlop. And it allowed me to buy a home, and that’s something that I, as just one person, wouldn’t be able to do most big cities. Since then, I’ve had a satisfying professional, creative, and social life. For the longest time, I was a bit ashamed to say, “I live in Regina and I’m from Saskatchewan.” But I’m getting over that. And I do feel a sense of responsibility to my community. Because I’ve lived here for a long time, I care about these people and about the socio-political climate here. I want to make my voice heard, and I’ve been given wonderful platforms to do that through exhibition-making, art-making, and writing.

G: I thought of this quote from John Waters, that he said at his lecture here in 2017. “Stay where you are. Everywhere is cool now.” I think that shame and stigma about saying where you’re from is dissipating.

B: John Waters also lives in Baltimore. He’s lived his whole life in Baltimore. It’s not a major metropolitan area; it’s a weird little city. And I wouldn’t say that John Water’s work is regionalist, but his films do reflect a particular worldview. They’re always little love letters to Baltimore and its oddities and quirks.

G: He’s made all his films in Baltimore. He’s stridently regionalist.

B: It speaks to the radical and subversive potential of staying where you are, and how the “decision” to stay or go is bound up in issues of privilege and economics. Can I ask you a personal question about your past? What was the first queer media that you were aware of? When were you aware of other people’s cultural queerness?

G: Well, lol, there’s this song Big Spender, by Peggy Lee? She wasn’t a queer man, but maybe should have been?

B: But she sang a song of longing that you could relate to?

G: Yeah! I was very young, like ten years old. That song seemed illicit and dangerous to me. I didn’t really understand why at the time. I also took comfort in over-the-top humour on TV – The Carole Burnett Show, and The Mary Tyler Moore Show. On the flip side, I was into The Avengers, especially Emma Peel – I wanted to be her. Then later, Lindsay Wagner in The Bionic Woman – I was drawn to female characters who could kick ass and still look great. Still am, actually. And TV personalities like Paul Lynde on Bewitched, and Alan Sues on Laugh In were fascinating to me.

B: You were able to read that code, as a kid?

G: Yeah. I was always drawn to the playfulness and camp in queerness.

B: Yeah. I was always drawn to that kind of humour, and I didn’t know why…Jim J. Bullock’s Hollywood Square, The Kids in the Hall…I think I’ve always had kind of a gay male sensibility. When I was in high school, my parents got a satellite dish, and then we had the Independent Film Channel and the Sundance Channel. I would wait until my parents went to bed, and then they’d play John Waters’ Pink Flamingos all these subversive queer films I had never heard of before. They played this Japanese film called Okoge, which is slang for “fag-hag” and I was like, “oh, that’s me….” I think I was figuring out what was going on sexuality-wise, but I was just like “Mom, Dad, I like international cinema.”

G: So, if some kid walks into this show, do you think it might have the same impact that these films had for you?

B: Or that Miss Peggy Lee had for you? I’d be delighted if this exhibition was some kid’s formative moment with queer identification. I’m drawn to Harley Morman’s work, and his use of childish, colourful materials like fusible plastic beads to address adult, mature states of being, like complex gender identities and sexual kinks. There’s a subversive, playful delight in that. Similarly, in Lasha Mowchun’s video, Second Skin, performers are writhing around with stretchy fabrics and leotards pulled up over their heads and limbs, abstracting their bodies. I think it speaks to impulses that I, and I think a lot of people have, to get outside of their bodies, or make their bodies strange, particularly in childhood.

G: I think about Nik Forrest’s work and how there’s no child alive that didn’t fantasize about…changing gravity.

B: Altering the orientation of the world.

G: I used to lie in my bed as a child and think “wouldn’t it be cool to walk on the ceiling?” You’d have to hop over the doorway and walk around the lighting fixtures. I’ve always liked Nik’s work because it’s really childlike. They’re creating a moment from my childhood imagination that I never got to experience, obviously. It speaks, to this fantastical thing we’re talking about, perhaps to the Prairie Gothic impulse.

B: Yes, I was wondering is this a regional influence? We’ve talked about the Prairie Gothic sensibility shared by many (but certainly not all) artists working in this region: dark, witty, perceptive, and strange work emerging from a sparsely populated, oft-overlooked, and sometimes challenging-to-live-in region. And that this exhibition looks at how queer artists, and artists with complex intersectional identities might fit, or not quite fit, within this framework. I think there is a sensuality, a slipperiness, and a sense of humour, perhaps an erotics of humour that runs through the exhibition.

G: When you live in a place like Saskatchewan or the Prairies, you fantasize about other worlds. New York, Paris, London…you romanticize other places. And there is a lot of that in this work. There’s something fantastic about travel, being somewhere else, or someone else, or something else.

B: I think all the artists in this exhibition are involved in queer world-making.

G: What do you mean by “world-making”?

B: I mean hypothesizing more fantastical ways of being in the world, and thus imagining a world where these ways-of-being made sense. Like Cindy Baker’s toile textiles that validate and celebrate fat, disabled, queer female bodies. And Daniel Barrow’s performance repurposes obsolete technology and imagines new technologies – like an animatronic head on a phallic wand that can read and translate text and be your friend and keep you company. And Phomohobes recombines images from old advertisements selling capitalist desire and recombine them so that they can speak to the idea of “desire” itself. Adrian Stimson queers the Napi story, reimagining Napi as this sexy, naked guy. Rosalie Favel casts herself as a Métis superhero warrior princess. Everyone is involved in the imagining of other worlds in a way that is kind of childlike, and kind of utopian. Imagining what the world can be, rather than what it is. Which is kind of a queer gift. And I think it does speak to the Prairies, which is something you mentioned, right?

G: When you’re queer in the Prairies, your sexuality and your geographical location are both marginalized. Imagined worlds are important for minorities, be they sexual, racial, gender, or other. Fantasy seems to have been a formative component to many of the works in the show. And yet I don’t think any of these artists are saying “please understand me and like me.” They aren’t pleas for acceptance, rather they’re creating more space for difference. It’s not for straight people, or the status quo, it’s for us.

B: People from the Prairies don’t own feeling isolated; you can feel isolated wherever you are. But the smaller the community you grew up or live in, the higher the chances you feel other by the general culture. Sexual difference is one factor, but there are lots of factors that might make you feel outside your culture looking in, and those people maybe have a higher tendency to become artists, or otherwise be invested in the project of world-making. So really, we’re undermining every premise we set up, and I’m okay with that.

G: Me too.

[1] Stuart Marshall, quoted in Caroline Evans and Lorraine Gamman, “The Gaze Revisited, or Reviewing Queer Viewing,” in A Queer Romance: Lesbians, gay men and popular culture, eds. Paul Burston and Colin Richardson (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), 40.

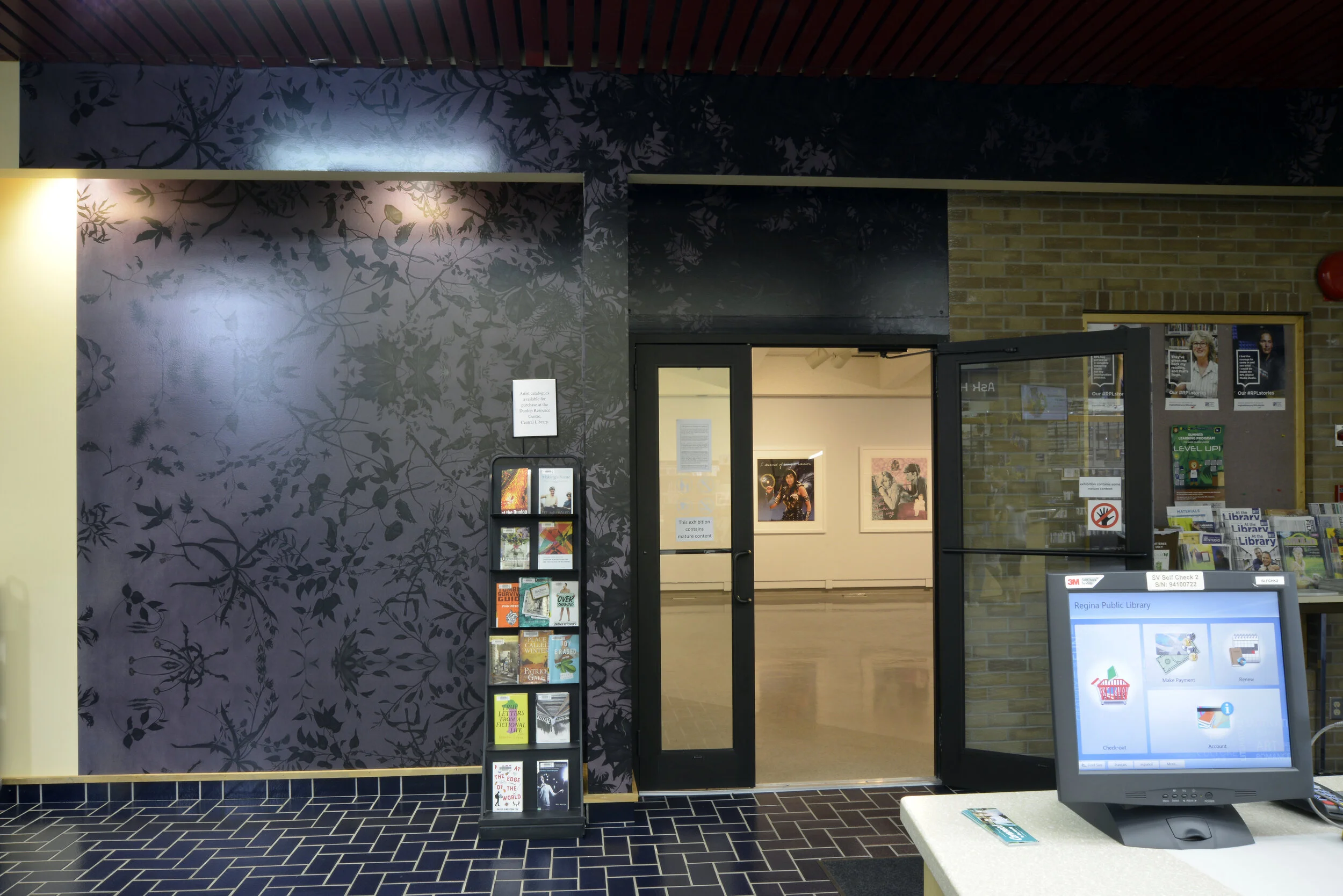

Installation Images ↑

All installation photos by Don Hall.