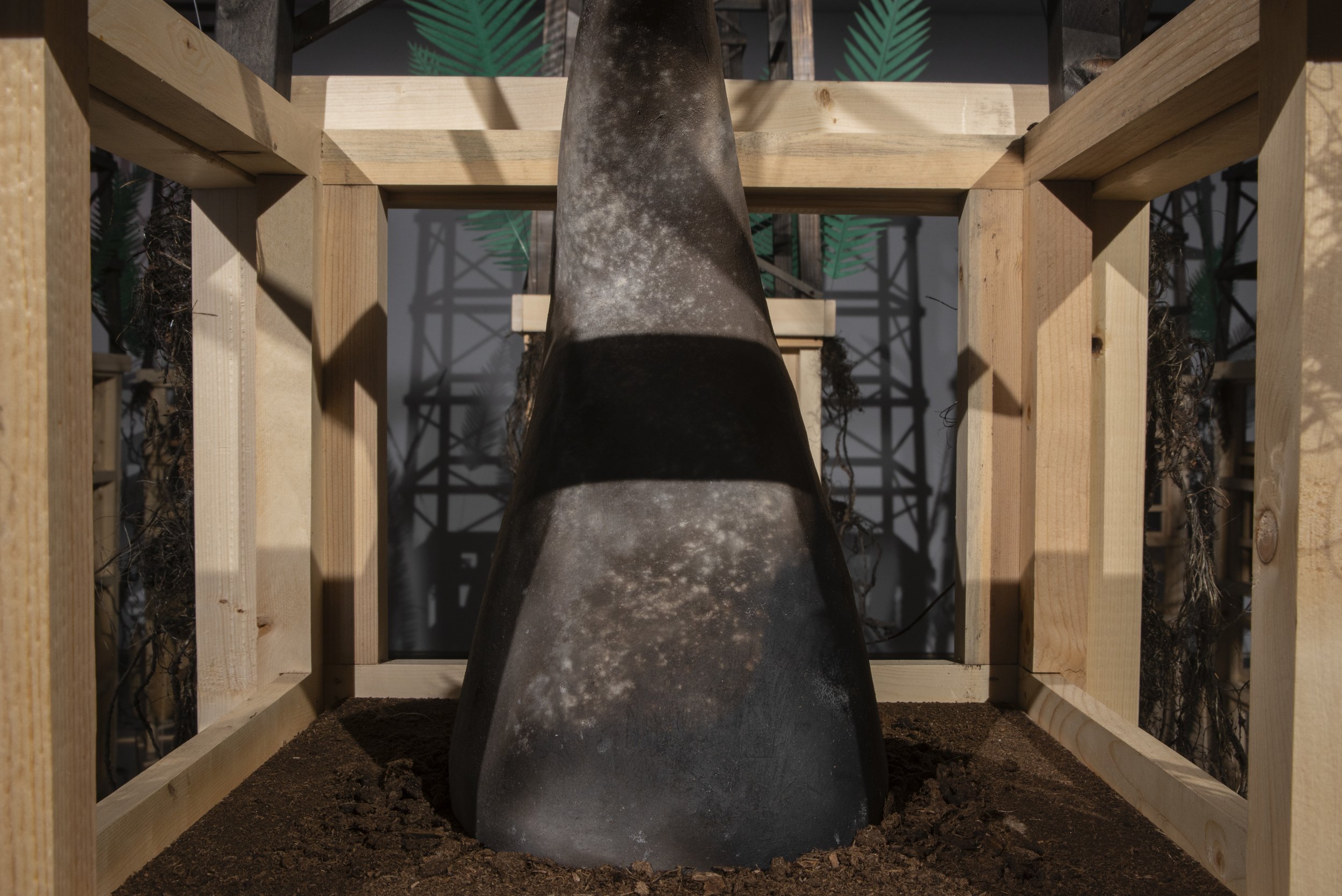

Rita McKeough, darkness is as deep as the darkness is , 2020. Courtesy the artist, Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo by: Donald Lee

In feel through the deepness to see, a new immersive exhibition by celebrated media and performance artist Rita McKeough, we journey below ground, where plants and animals gather and try to make sense of the activities of machines that labour above. Together, we are invited to imagine interspecies relationships beyond the destructive exploitation of extractive industrialism.

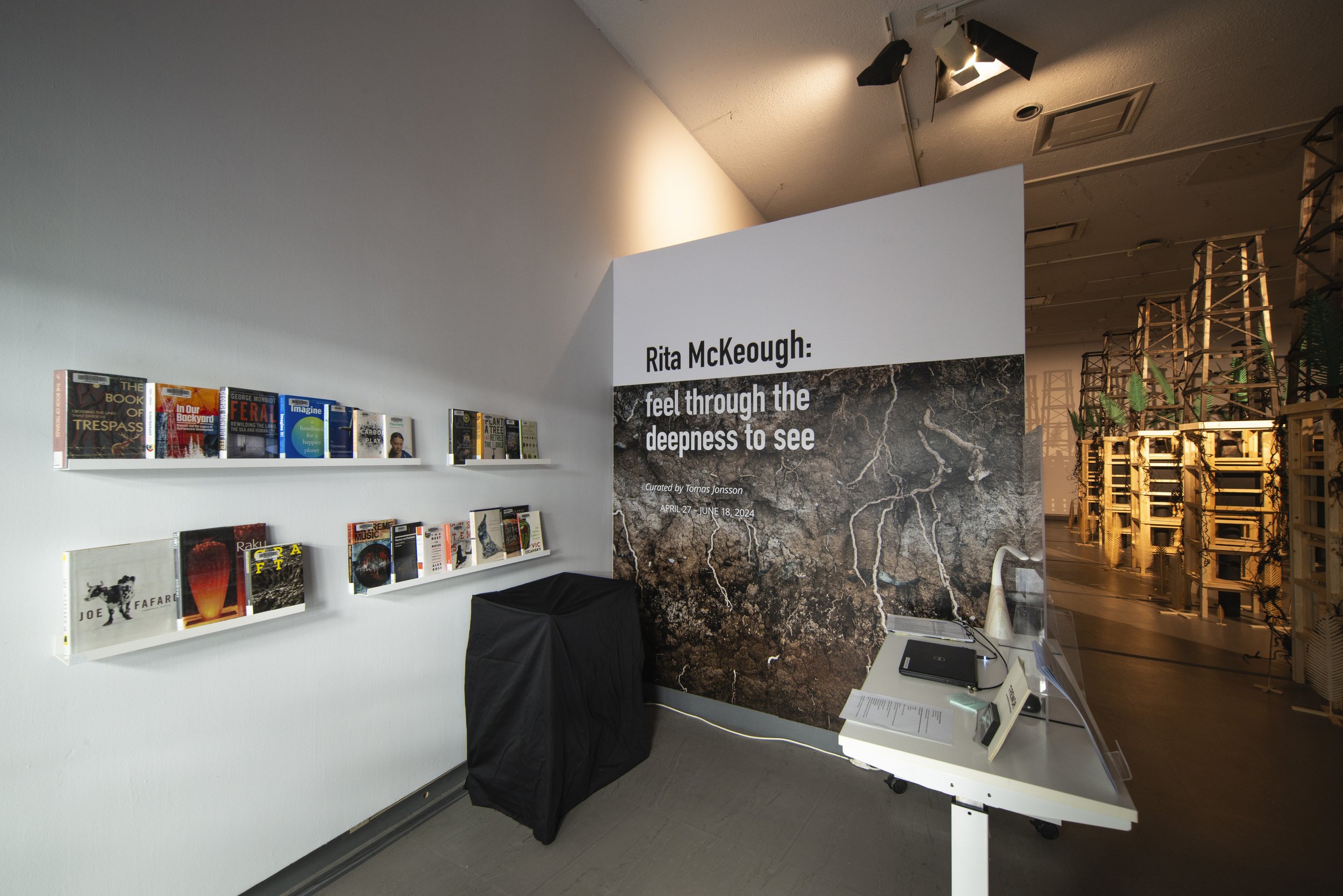

The exhibition is the third iteration of a series, including darkness is as deep as the darkness is, curated by Jacqueline Bell at the Walter Philips Gallery, and dig as deep as the darkness, curated by Dylan McHugh for the Richmond Art Gallery.

The exhibition is supported by the Canada Council for the Arts, the Alberta Foundation for the Arts, and the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Outstanding Artist Program. The artist would also like to thank the Canada Council for the Arts, the Alberta Foundation of the Arts and Alberta University of the Arts, Bemis Centre for Contemporary Art for their generous support and everyone who contributed to the production of this work.

Essay ↑

Underground With You in Rita McKeough’s feel through the deepness to see

By Lindsey french

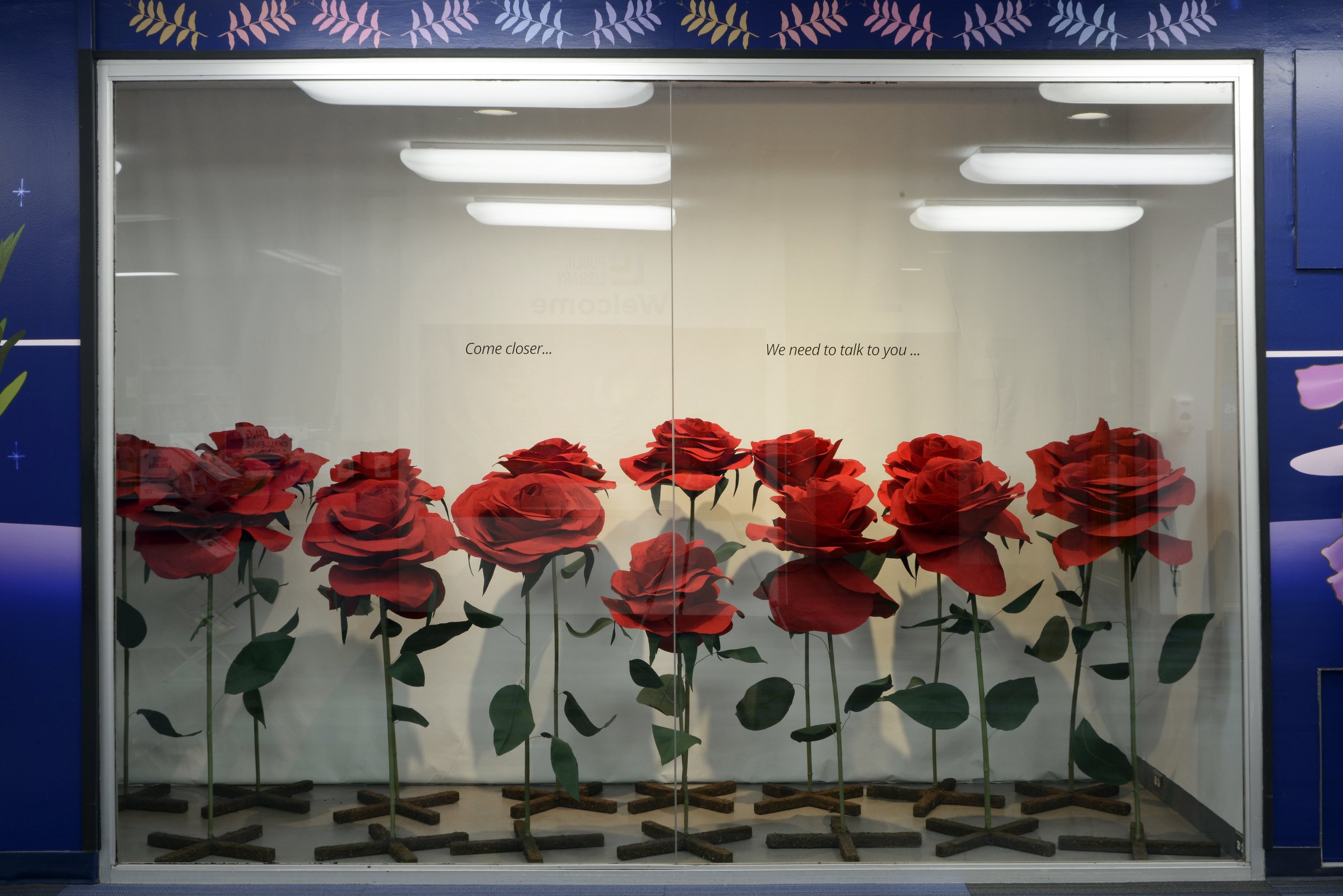

“Hey, hey! Come closer. Come closer. We need to talk to you. We need your help.” --Roses

We wanted to hear what the roses say -- and now we find ourselves in an underground bunker where insects, animals, and plants are recovering from the disaster above. We are guests, listening in on a conversation between bear and cranberry as they check in on each other in the wake of disaster.

What does it mean to be a listener? As a social practice, listening establishes relationships. The deeply contextual nature of listening is complicated by inherent biases, worldviews, and approaches that we bring to our listening practices, a concept which Dylan Robinson describes as listening positionality. Listening positionality is not easily summarized by our identity markers, but is a richer, thicker process of understanding the social contexts we listen among – and when we are guests in someone else’s sound territories.1 Listening built on relationships of shared power can resist assimilative and extractive logics that guide our relationships with other beings.

The sonic space we visit in the bunker of feel through the deepness to see includes a conversation between bear and cranberry, above a chugging combustion engine and heartbeat rhythm, occasionally interrupted by a blast of loud sound. Though this is an imaginary world, it's a dangerous one, and we are implicated as both guests and witnesses within the narrative of this interspecies assemblage that, while related to, is different from our own.

feel through the deepness to see operates with a dose of anthropomorphism, but McKeough’s aim isn’t to prescribe human characteristics to these plants and animals. Instead, she’s interested in translation between species, an interest I share – not because translation allows full understanding, but precisely because translations are flawed. There is value in developing relationships of uncertainty which make such interspecies queries possible. Gaps in translation create spaces for vulnerability, and confronting the limits of understanding can create conditions for learning or change.

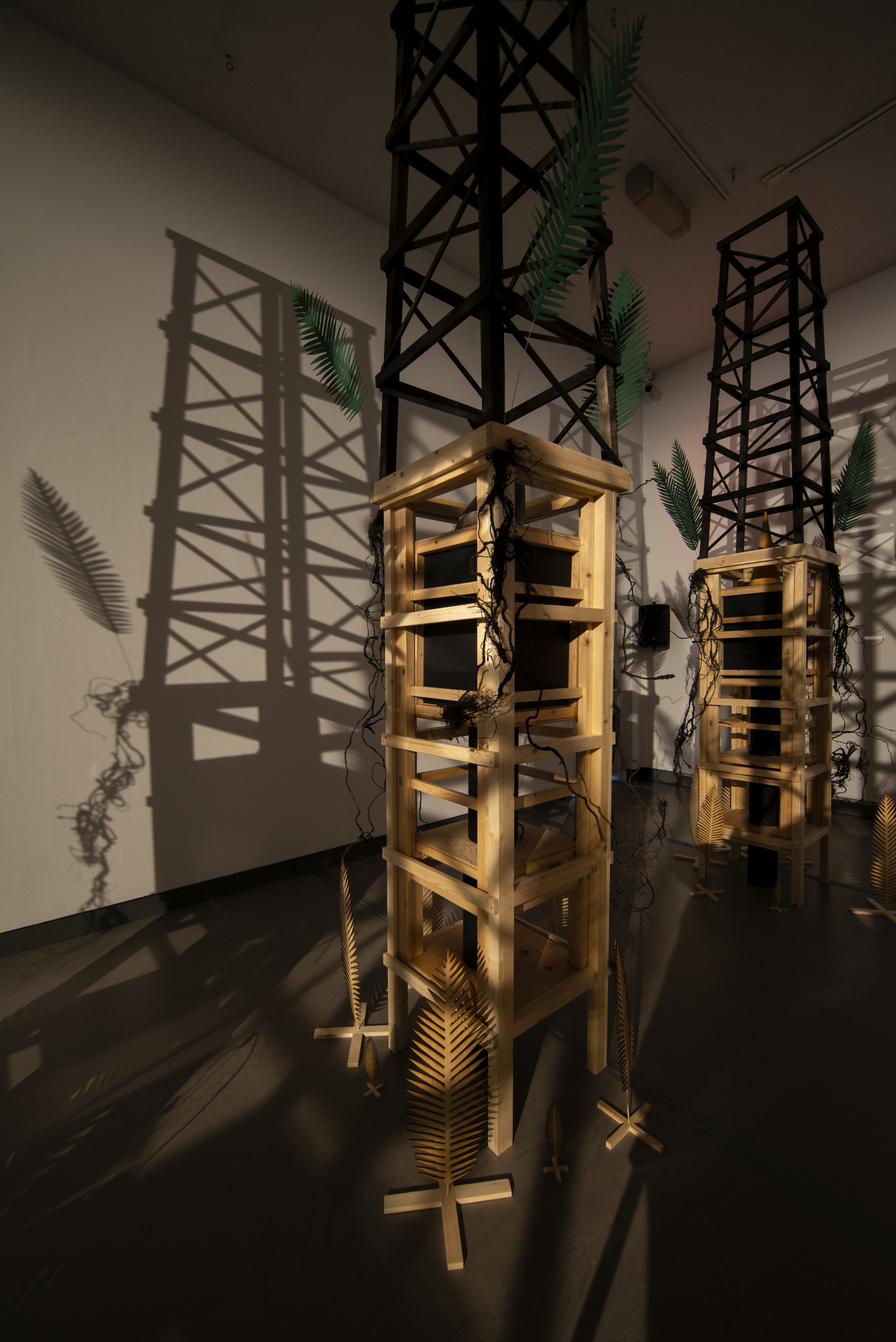

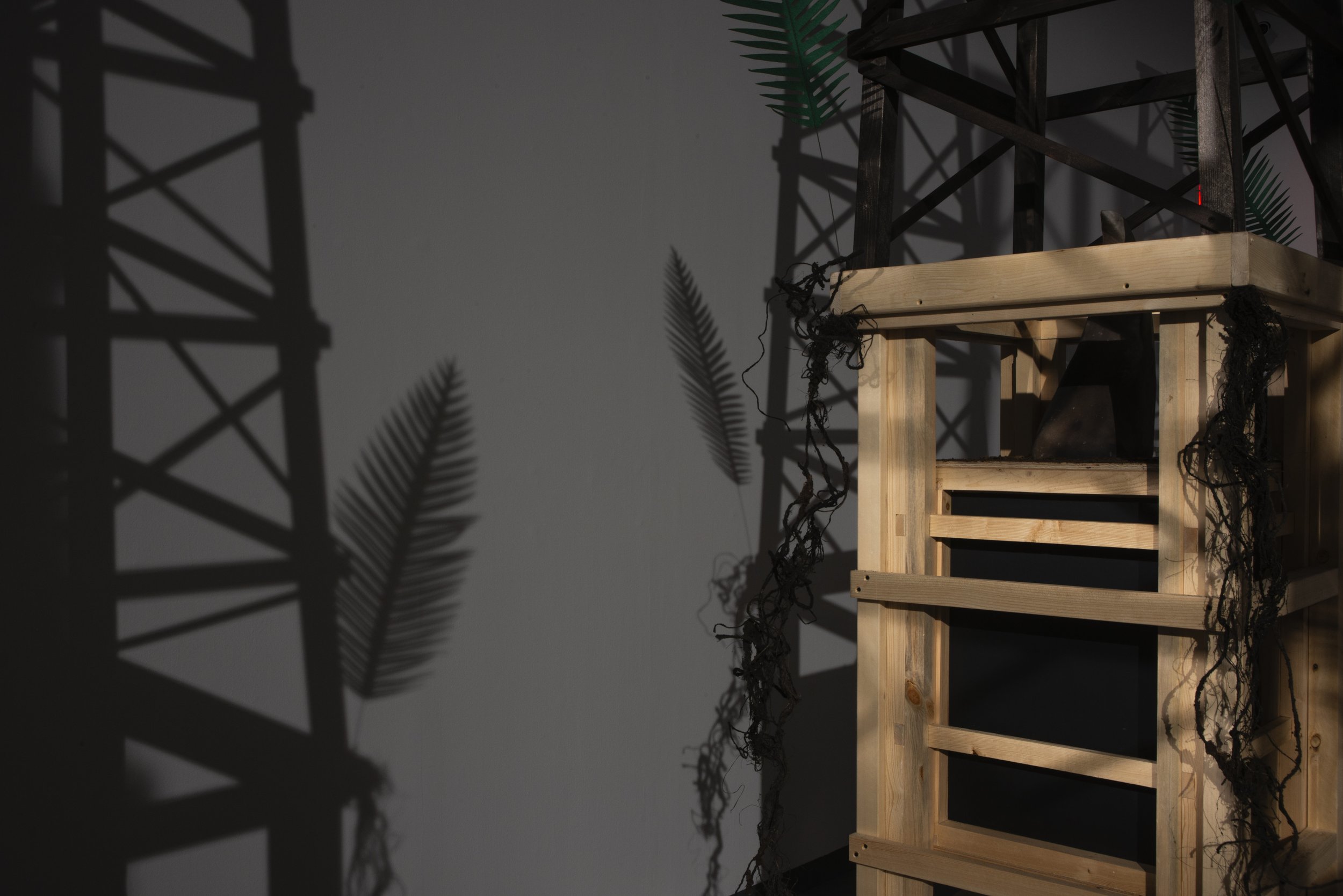

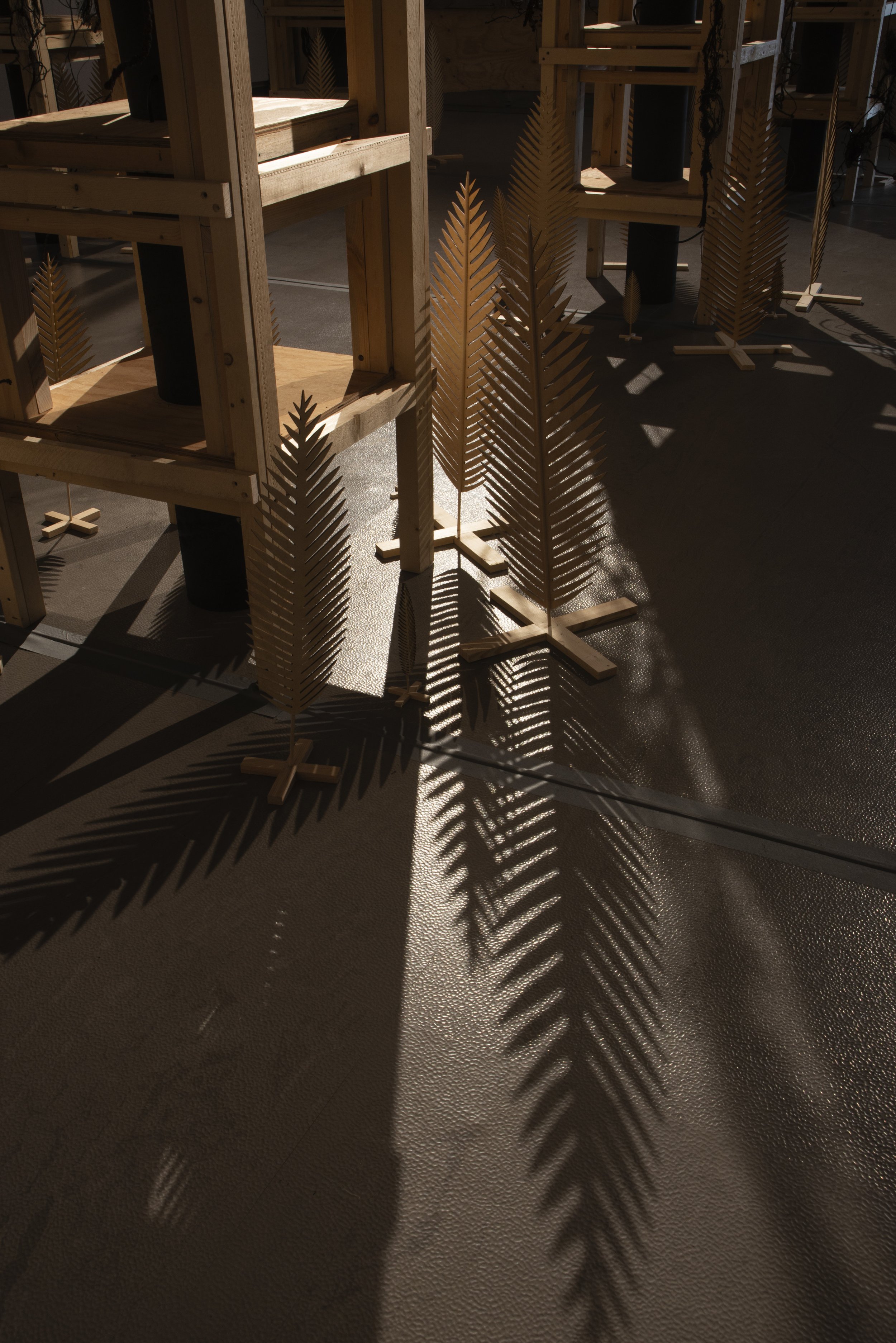

Some biological definitions consider communication to be established when a signal from a sender causes a change in the behavior of the receiver.2 This scientific definition of interspecies communication focuses less on a message’s fidelity, and more on the capacity of the receiver to be affected. I feel vulnerable when I enter the main installation room where extraction towers loom above, duplicated by cast shadows. Sword ferns stand guard, their tracery of dangling roots webbing across this subsoil environment, while claws and horns rise up in choreographies of warning signals. I feel the stakes of the situation before I can describe what they are.

As my eyes adjust to the darkened room, I see pale ghosts of sword ferns at the blanched bases of the extraction towers. They are the honorable dead, having ingested and transformed toxins into their bodies in resistance to what Rob Nixon might refer to as the “slow violence” of environmental degradation, often invisible and impacting already disempowered communities.3 Here, we’re in the midst of this violence and its resistance, alongside the sword ferns and their horned and clawed comrades.

For decades, McKeough’s work has asked questions about our relationship to land through humour, imagination, and introspection. At Saskatoon’s Mendel Art Gallery4 in 1986, McKeough offered a dark yet witty glimpse into the future in her installation Afterland Plaza, which she developed after researching uranium mining around Saskatchewan. Inside the gallery, a mall of the future was hawking polluted real estate, with displays of cows amidst uranium molecules, residential homes with filtered air propped above unlivable landscapes, and a soundtrack of mall announcements and infomercials. Years later for this exhibition at the Dunlop, she considers post-extractive futures of the province again, this time offering a different access point. Though both installations direct us toward critical reflection, any subtle whiffs of satire that may have floated through the sales pitches in Afterland Plaza’s filtered air are not detectable in the atmospheres of commoning of the underground burrows in feel through the deepness to see. Here, we gather earnestly in the dank richness of shared soil and of working through grief and resolve together, with care. There is a chill of sadness in the installation, but you don’t have to feel the sadness alone. You, too, might be buried underground in the future– but more importantly, you are there now, alive and witnessing the richness of interspecies coalition forming in the tangle of subsoil networks.

The animals and plants in McKeough’s installation can’t escape the persistence of the machine, and neither can we –it resonates as a sonic beat within our bodies in the gallery, but also beyond, as we’re all implicated in extractive economies and technologies in different ways. Machines have cut the installation’s ferns from wood and programmable logic controllers trigger the installation’s theatrics for viewers. It is not necessarily the machines, but the extractive logics which insist (as we hear from the ferns), on “taking everything” and “sucking up everything that is not them.” Machines, like listening, can be turned toward extraction and assimilation; or they can be turned against it, inclined instead toward urgent stories of an era. McKeough crafts imaginary worlds and experiences of deep feeling, inviting us to investigate our own positionality in the very real narratives of extraction that play out in the region. She reminds us that resistance forms underground, and it’s not too cool for you to join. The roses’ request is transparent. You’re invited to listen, but you’re listening to a question – what are we going to do? In the rich coalitions of the soil, you become part of the we. You can be underground too, and in the darkness, we can feel our way forward together.

Lindsey french (they/she) is an artist, educator and writer whose work considers positions of listening, receptivity, and marginality as valid and active political and communicative positions. Lindsey has shared their work widely in museums, galleries, screenings, and D.I.Y. art spaces including the OCAD’s Onsite gallery (Toronto), SixtyEight Art Institute (Copenhagen), and the Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago), along with collaborative projects at The Chute (Pittsburgh) and for the 4GROUND: Midwest Land Art Biennial (Shafer, Wisconsin). Recent publications include chapters for Ambiguous Territory: Architecture, Landscape, and the Postnatural (Actar, 2022), Olfactory Art and The Political in an Age of Resistance (Routledge, 2021), and Why Look at Plants (Brill, 2019). Lindsey earned a BA through an interdisciplinary course of study at Hampshire College, and an MFA in Art and Technology Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 2021, they moved from Pittsburgh to Treaty 4 to teach as an Assistant Professor in Creative Technologies in the Faculty of Media, Art, and Performance at the University of Regina.

Artist ↑

Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall

Media ↑