Image: Shelley Niro, Toys Aren't Us - Day at the Beach, Digital Photography, 2017. Photo: courtesy of artist.

For over 30 years, Shelley Niro has challenged dominant perceptions of Indigenous people throughout her extensive art and filmmaking practice. Often using humour and a flair for storytelling, Niro addresses stereotypical representations of Indigenous people to expose powerful colonial attitudes. From her unique perspective as a Mohawk artist, Niro frequently casts herself and family members in her work to harnesses her familial agency. Niro’s work continually stresses the significance of the land within Indigenous worldviews, languages, and ways of being.

Shelley Niro is a member of the Turtle Clan, Bay of Quinte Mohawk from the Six Nations Reserve. She holds a degree from Ontario College of Art and a Master of Fine Art from the University of Western Ontario. Niro has exhibited across Canada has work in collections of the Canada Council Art Bank, Canadian Museum of History, and Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography. Her award-winning films have been screened in festivals worldwide, and she presented work at the 2003 Venice Biennale. Shelley Niro lives in Brantford, Ontario.

Artist ↑

ESSAY ↑

Ode to Shelley

By Ruth Cuthand

Shelley Niro and I first crossed paths in 1989 at the opening reception for Changers: A Spiritual Renaissance, in Toronto’s Harbourfront gallery. This was an Indigenous women group exhibition curated by Shirley Bear. It was an inspiring weekend and I met women from all over Turtle Island. After that initial meeting, I have followed Niro’s work over the years.

What do I know about Shelley? I know she loves her family, her community, knows stories of her culture, incredible sense of humour and makes art the way she wants. She beads, draws, paints, makes beautiful hats, does photography and makes short films and feature films. I understand her rejection of mastering one aspect of art making. Why master something, when you can use all types of media? The art world likes to package artists as “the painter” and when you change media, that world gets nervous because you are supposed to stay in your lane. For us art is supposed to be fun and it is about learning new things, finding the media that fits the project.

Shelley and I were born in the same year, 1954. This was the time of the fabulous fifties, post war economic boom, better health and home ownership. In the West, Indigenous people were left out. I remember the small 3 room house with dirt floor, central wood stove and water barrel outside. Meanwhile, Mohawks were building New York. I remember when the Canadian Bill of Rights of 1960, Indigenous people became citizens with all the rights to vote and were no longer wards of the Government.

In the 70’s both Shelley and I became mothers of daughters. Being mothers would have an impact on our art careers. During the 80’s Robert Houle curated an exhibition New Work by a New Generation at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina. This was a ground-breaking group exhibition that showed contemporary work by Indigenous artists, who would dominate the Canadian art scene. Shelley and I continued to make work.

We both have a wicked sense of humour and laugh and laugh when we visit. Indigenous people have a type of humour often referred to as “Survivor” or black humour. We tease each other and we laugh when there is a group of us. I have used humour as a way to get white people to open up and listen. My humour is a sense of shared experience with other Indigenous people. Shelley uses her humour to introduce the unexpected. Her sisters wear beehives and red heels. Her mother lays across a hood of a car and smiles. Everyone is in on the joke and the joy. There is great deal of joy, it is as if Shelley is yelling” We are here, we are Mohawk women!”

Historically I come from an egalitarian society and Shelley comes from a Matriarchal society. Patriarchal colonization ruined everything! We both are interested in the lives of Indigenous women and the effects of colonialism. Oka happened, Mohawks trying to keep their burial ground from development of a golf course. Golf courses are the most useless use of land, lawn that has to be watered and mowed so people can hit a little white ball around. Oka had every Indigenous person on the edge of their seat. Would we win? Would the Surete du Quebec kill everyone? Would the army invade and blow everyone up? Would Indigenous people be okay as racism reared its ugly head?? As we know the end was genius, the warriors decided to go home. No truce no losers, just the end. Shelley and her sisters took to the streets of Brantford. They did their hair and wore red heels. I drew images of the incident with anger and very little humour.

There is still no resolution.

“In her Lifetime” tells the story of many Indigenous women. I can relate to “Native issues would never be resolved in her lifetime.” I live in the place where Idle No More was birthed by four women. I was very concerned when the Conservative government of the day stopped protecting rivers. I went to a rally put on by the women, I was very inspired. Here was a grassroots movement that had nothing to do with any government. We round danced in malls, all across the West. Regular people just dancing as white capitalists closed their shops. It was exhilarating to see people gathered with such joy.

We live in interesting times and I hope the next generation sees Native issues resolved in their lifetime.

Ruth Cuthand is a Canadian artist of Plains Cree and Scottish ancestry. She is widely considered an influential feminist artist of the Canadian prairies and is lauded for her unflinching interpretation of racism and colonialism. Her work challenges mainstream perspectives on colonialism and the relationships between “settlers” and Natives in a practice marked by political invective, humour, and a deliberate crudeness of style. Born on Treaty 6 Land, near Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, Cuthand is a member of Little Pine First Nation, but spent most of her childhood in Cardston, Alberta near the Blood Reserve, where she met artist Gerald Tailfeathers at the age of 8, which compelled her to pursue a career as an artist. Cuthand earned a BFA from the University of Saskatchewan in 1983, and a MFA, also from the University of Saskatchewan in 1992. In the period between her degree programs, Cuthand did some post-graduate work at the University of Montana in 1985. During her education, she worked in printmaking, but later switched to painting.

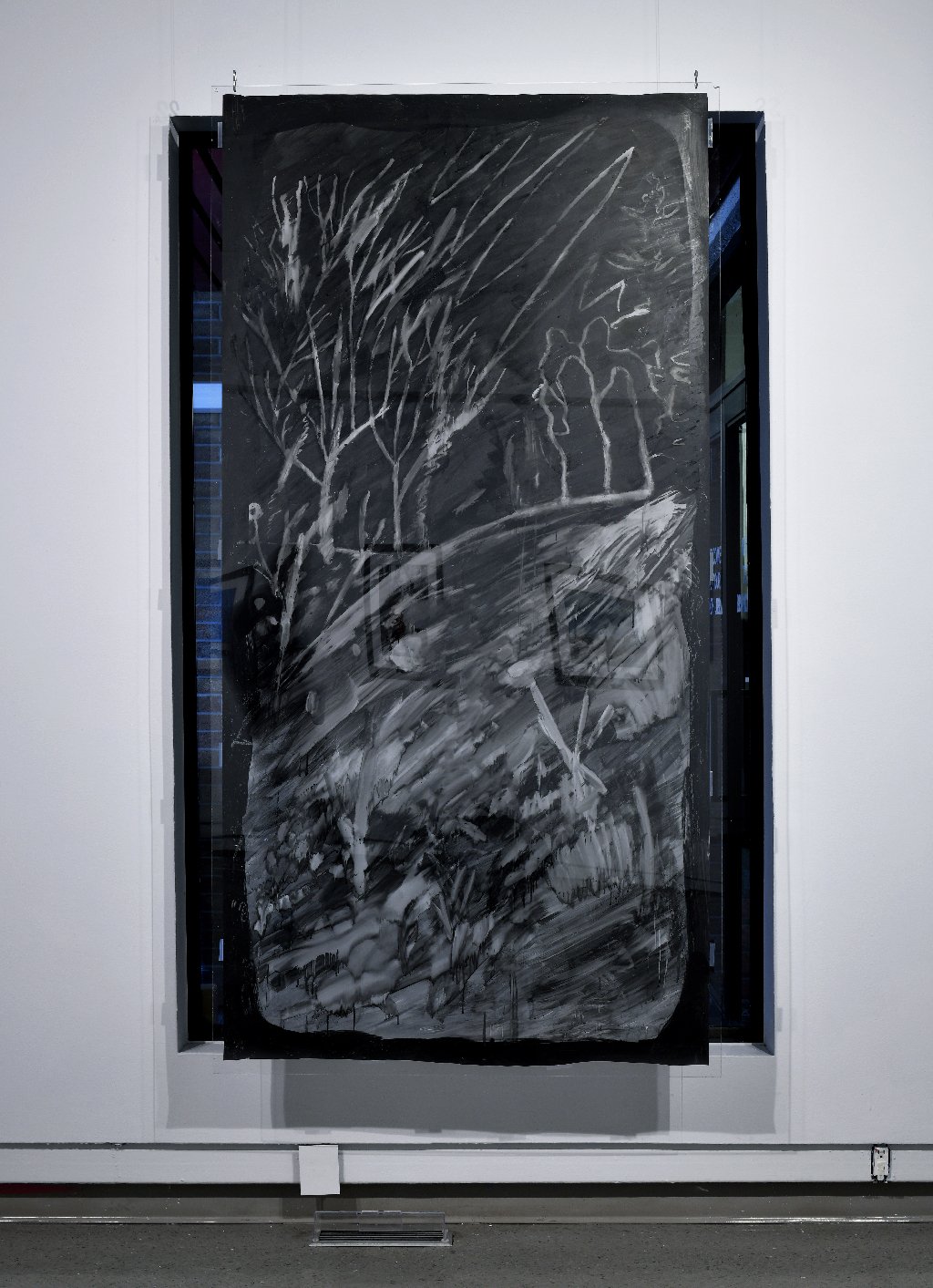

Installation Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall