Image: Alana Bartol, To Dig Holes and Pierce Mountains, Crowsnest Pass, Alberta, 2020. Photo: blkarts.ca

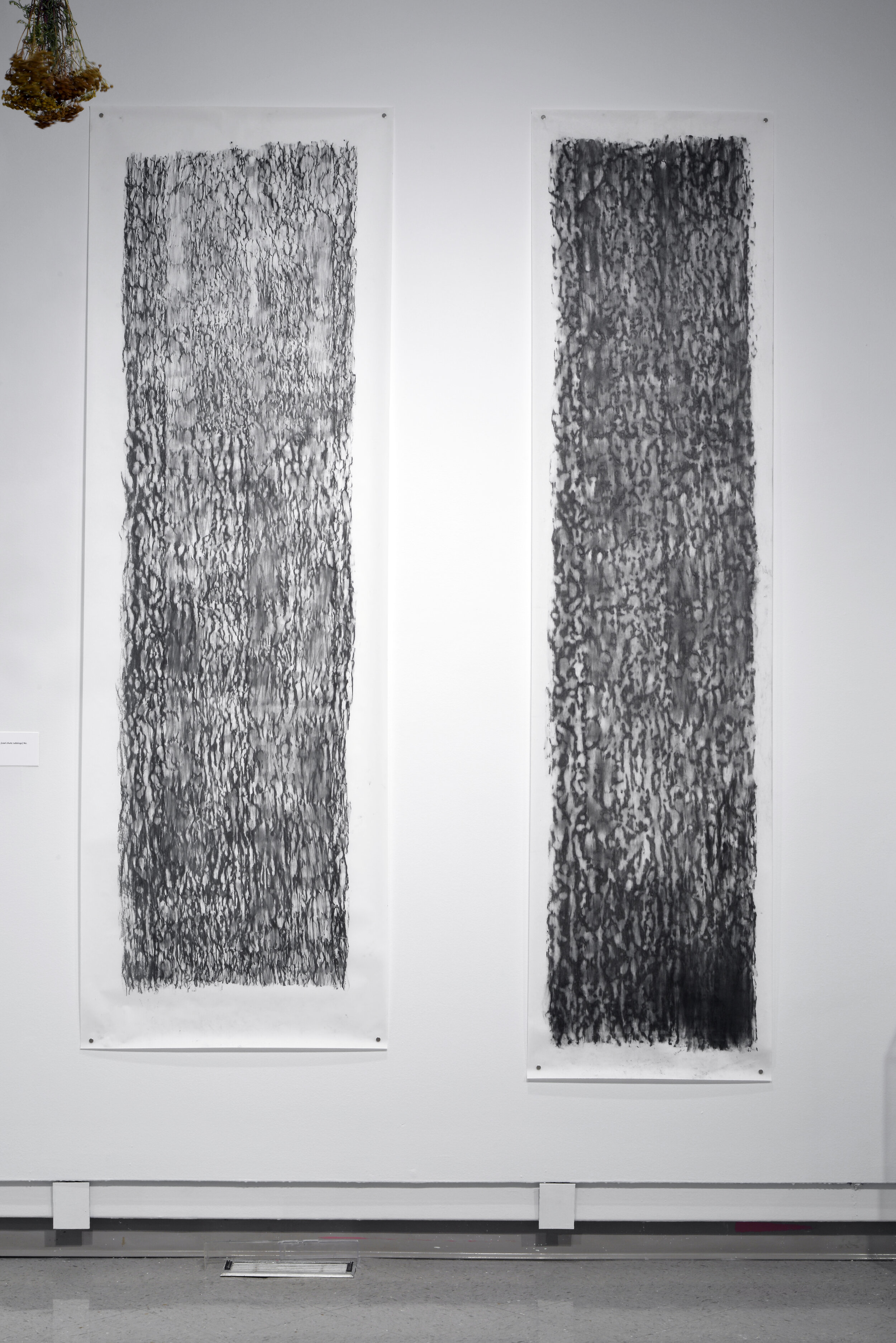

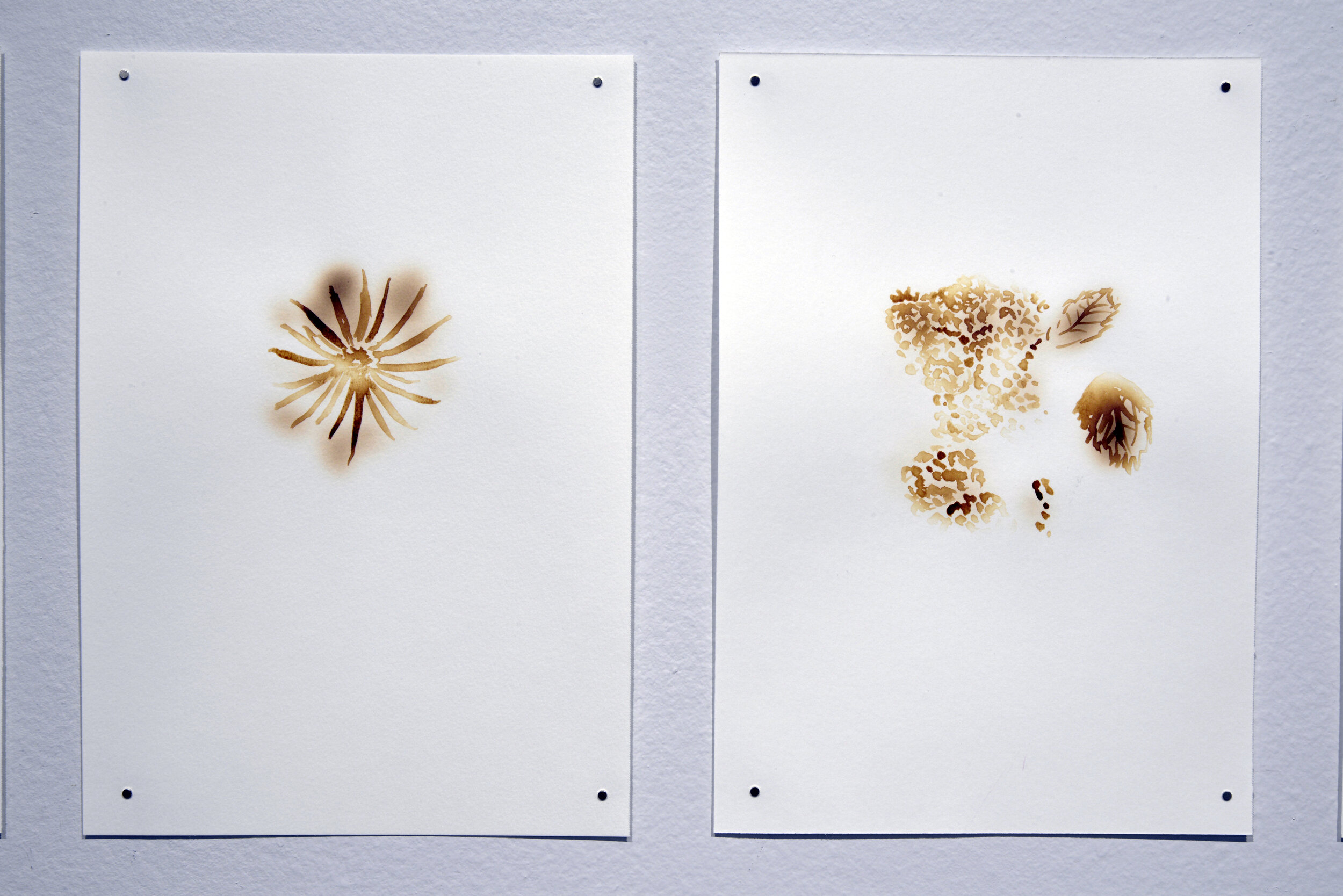

This exhibition draws on Bartol’s work with dowsing (she comes from a long line of water witches) and the history of dowsing in connection to mining/resource extraction. Specifically, Bartol researched Martine de Bertereau, one of the first (recognized) female mineralogists and mining engineers in 17th century France who traveled Europe in search of mineral deposits utilizing specialized divining instruments and other techniques including botany. Martine de Bertereau was accused of witchcraft and died in France while in prison. The story of de Bertereau is a complex one that points to the violence of resource extraction and the development of capitalism that she both participated in and was killed by. In her artwork, Bartol uses dowsing to ask audiences to reconsider consumption-driven relationships to the earth and what are known as 'natural resources'.

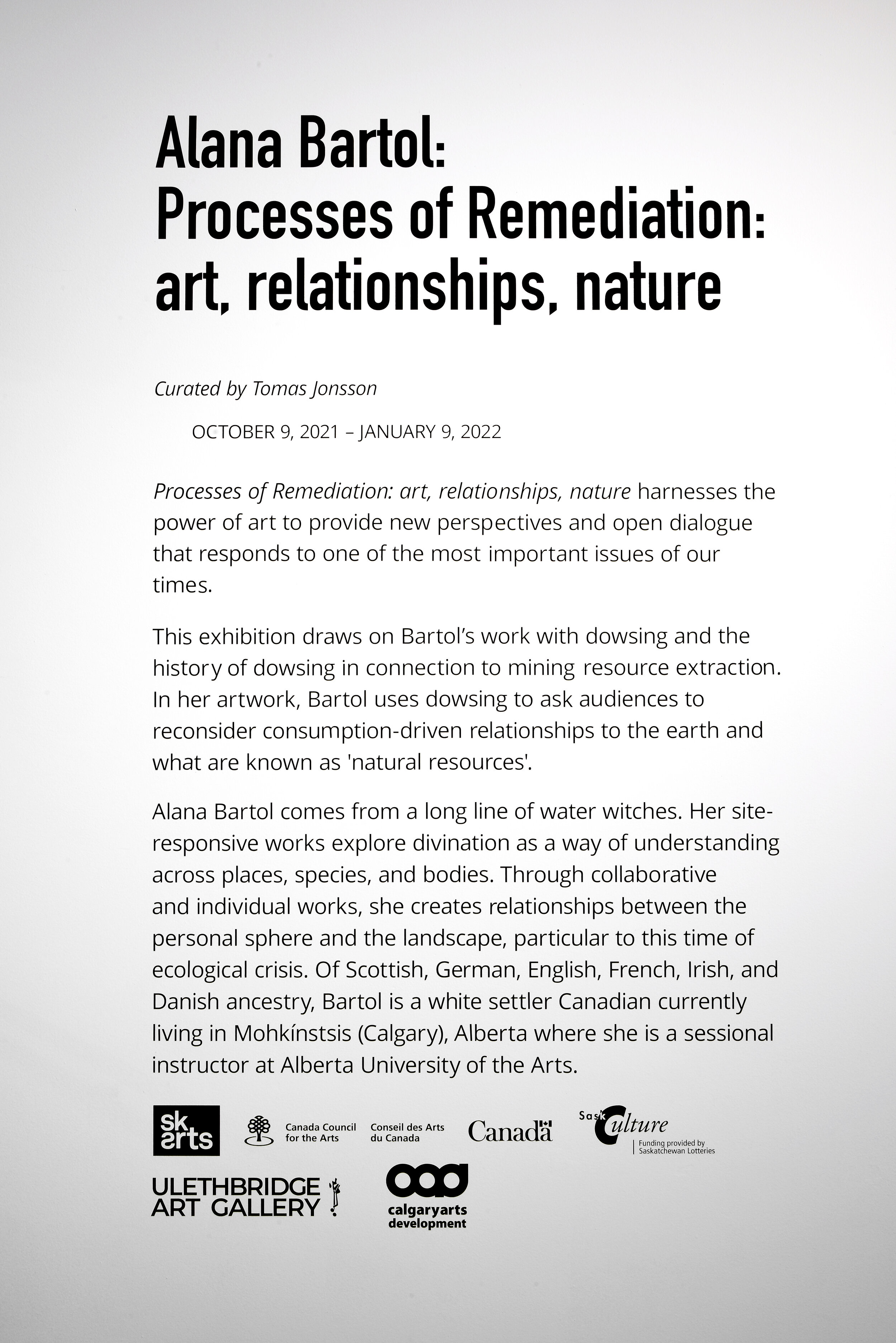

Alana Bartol comes from a long line of water witches. Her site-responsive works explore divination as a way of understanding across places, species, and bodies. Through collaborative and individual works, she creates relationships between the personal sphere and the landscape, particular to this time of ecological crisis. Of Scottish, German, English, French, Irish, and Danish ancestry, Bartol is a white settler Canadian currently living in Mohkínstsis (Calgary), Alberta where she is a sessional instructor at Alberta University of the Arts.

Artist ↑

ESSAY ↑

Processes of Remediation: Art, Relationships, Nature

By Josephine Mills

What we contemplate here is more than ecological restoration; it is the restoration of relationship between plants and people. Scientists have made a dent in understanding how to put ecosystems back together, but [these] experiments focus on soil pH and hydrology — matter, to the exclusion of spirit. […] We are dreaming of a time when the land might give thanks for the people.

- Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, p. 263

Processes of Remediation: Art, Relationships, Nature provides a poetic engagement with what became a pressing environmental issue in Southern Alberta in 2021.

When I began working with Alana Bartol at the start of 2020, she proposed a project that explored the history of coal mining and the coal deposits in and near Lethbridge. Her focus was to build on the work she had done related to orphan oil wells and the woefully inadequate land reclamation that is allowed to happen by the oil and gas industry. Her focus for this new work would be to address the question: what does remediation mean in this moment of ecological crisis?

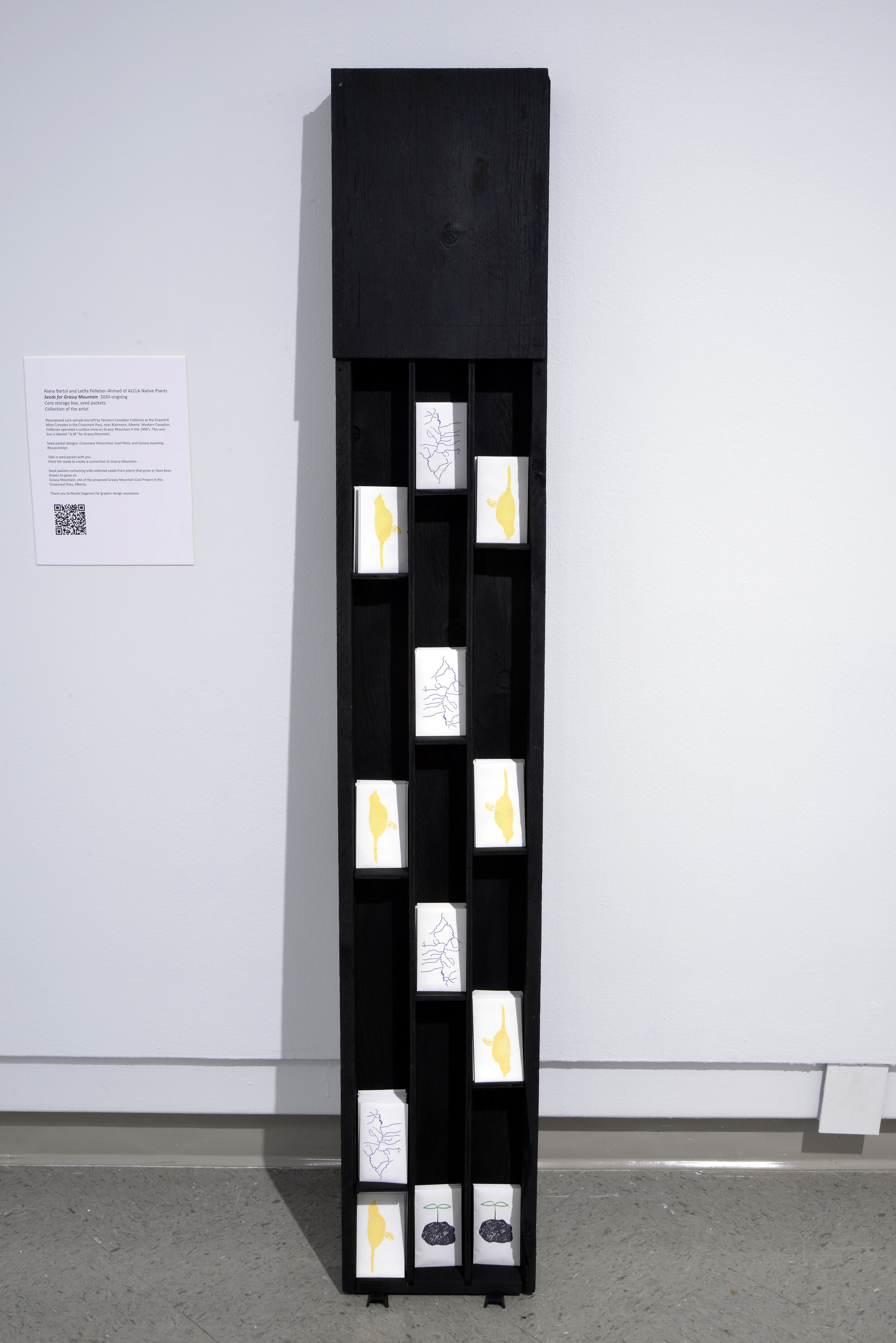

When Bartol began Processes of Remediation, we had no idea that coal mining in our area would move from an historical issue to an immediate threat. In June 2020, the Alberta government rescinded the policy preventing open-pit coal mining and thus removed the protection for the Eastern Slopes of the Rockies. This opened the door to proceed with open-pit coal mines in the region, with Grassy Mountain in the Crowsnest Pass being the first up for approval. Fortunately, the opposition to this one mine was successful, and the pressure to safeguard the watershed that provides water to the area, including the city of Lethbridge, prevailed (although there are still several more proposed mines going through review).

The approach for creating Processes of Remediation was an experiment of sorts. Rather than focusing on the end product, the project was designed to support Bartol in having the time and resources to conduct research so that she could build a new body of work. The plans for the project had to shift dramatically with the lockdown for COVID-19, and, as a result, Bartol created the website dowsinganddigging.com to share her research and work in progress. With changes to allow for COVID-19 precautions, the University of Lethbridge Art Gallery connected Bartol with scientists on campus, Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) knowledge keepers, and the university’s Coutts Centre for Western Canadian Heritage (a botanical garden near Nanton, Alberta). The gallery also paid artist’s fees and Elder honoraria for the residency phase in addition to exhibition fees. My hope was that we would then get to present an incredibly rich result. While I was of course dismayed at the sweeping decision to remove protection for the Eastern Slopes of the Rockies, the gallery’s approach with Bartol far exceeded my plans, as it placed her in a position to immediately address the implications of the Grassy Mountain project, and thus her artwork could add to the discussion as it unfolded.

The research aspects of Processes of Remediation go beyond Bartol visiting the Galt archives or learning about local plants, soil health, and Blackfoot perspectives on ecosystems. When one hears the word “research” in connection with art, it is most likely that people imagine this kind of activity — conducting research in advance of making artwork. More recently, the term “art as research” has become a buzz phrase. Mostly it is used loosely, as a way of saying that art has value and is important, that there is intellectual activity involved, and that artists think, they don’t just spontaneously create. However, there is much more involved with this perspective on the function and process of art.

In his book Strange Tools: Art and Human Nature, philosopher and cognitive scientist Alva Noë explains how art is a method of investigation, and thus provides a means to understand how we function in the world around us. He states that “art provides us an opportunity to catch ourselves in the act of achieving our conscious lives, of bringing the world into focus for perceptual (and other forms of) consciousness.”[1] Noë describes how art can help us see and make sense of the level at which we are organized — the level of our daily habits. We are embedded in this level of activities and cannot analyze the structures that organize our behaviour and emotions because we are enmeshed within them. But, Noë argues, with art, we can understand our environment: “A work of art is a strange tool, an alien implement. We make strange tools to investigate ourselves.”[2] Noë’s approach describes a complex idea of art as research and extends that idea into what happens when people engage with art. There is the research done by artists in developing and producing their work, and there is also the investigation that continues to happen with the viewer or participant. Central to his argument, these aren’t two separate areas: the making and the engaging are both part of the whole that produces the rich potential of what art does as a form of investigation of ourselves.

Processes of Remediation: Art, Relationships, Nature is a social practice exhibition, but it is most certainly not didactic. The subtle, beautiful artworks invite visitors to look closer, to take their time, to think about what could be lost, and to consider relationships between themselves, other living beings, and the land. I am grateful that the Dunlop Art Gallery is presenting the exhibition and that people in Southern Saskatchewan will have the opportunity to see Bartol’s exceptional project.

[1] Alva Noë, Strange Tools: Art and Human Nature (New York: Hill and Wang, 2015), xii.

[2] Noë, Strange Tools, 30.

References:

Alva Noë, Strange Tools: Art and Human Nature (New York: Hill and Wang, 2015).

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013).

Installation Images ↑

Photos by Don Hall